Researchers Grow Biological Hard Drive From Bacteria

May 10, 2012

on

on

In the future we might never run out of disk space again. Researchers are developing a method to grow storage devices from bacteria. So when you get that loathed message ‘your startup disk is almost full’ instead of cleaning up your disk, you set bacteria to work to generate some extra disk space.

Researchers at Britain's University of Leeds and Japan's Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology use bacteria to organically grow tiny magnets which can store bits of data.

Conventionally, hard disks are manufactured by breaking down a big magnet into nanoscale pieces called grains which are deposited on a disc. A few hundred grains form a magnetic region which can store one bit of information.

The increasing capacity of storage devices is the result of the miniaturization of components. But this can’t go on indefinitely, lead researcher Dr Sarah Staniland warns.

‘We are quickly reaching the limits of traditional electronic manufacturing as computer components get smaller. The machines we've traditionally used to build them are clumsy at such small scales. Nature has provided us with the perfect tool to circumvent this problem’, she said in the university press release.

Instead of using the top down approach of breaking down a magnet, the researchers are having nature build tiny magnets from scratch.

For this purpose the team used the bacterium Magnetsopirilllum magneticum, a naturally magnetic microorganism. It uses its magnetic property to navigate along the earth’s magnetic lines. The bacterium derives its magnetism from ingesting iron. Once in its system the iron interacts with a protein producing a magnetic mineral called magnetite.

Once they understood how the Magnetsopirilllum magneticum worked its magic, the team figured out how to replicate this process outside its body.

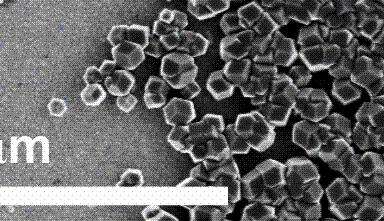

They coated a surface in gold and added the protein in a chessboard pattern. When the surface is dipped in an iron solution, those squares covered with the protein start producing nanocrystals of magnetite. Each square covered with nanomagnets can store one bit.

The research is still at an experimental stage. The squares are 20 micrometers wide, that’s 2000 times larger than magnetic bits in conventional hard drives. But Staniland is confident they can bring the size down.

It is not just the problem of the fast approaching miniaturization limits of silicon-based electronics the researchers are hoping to solve. They’re looking to radically change the future of electronics. ‘Our aim is to develop a toolkit of proteins and chemicals which could be used to grow computer components from scratch’, Staniland said.

For more information: Leeds.ac.uk

Researchers at Britain's University of Leeds and Japan's Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology use bacteria to organically grow tiny magnets which can store bits of data.

Conventionally, hard disks are manufactured by breaking down a big magnet into nanoscale pieces called grains which are deposited on a disc. A few hundred grains form a magnetic region which can store one bit of information.

The increasing capacity of storage devices is the result of the miniaturization of components. But this can’t go on indefinitely, lead researcher Dr Sarah Staniland warns.

‘We are quickly reaching the limits of traditional electronic manufacturing as computer components get smaller. The machines we've traditionally used to build them are clumsy at such small scales. Nature has provided us with the perfect tool to circumvent this problem’, she said in the university press release.

Instead of using the top down approach of breaking down a magnet, the researchers are having nature build tiny magnets from scratch.

For this purpose the team used the bacterium Magnetsopirilllum magneticum, a naturally magnetic microorganism. It uses its magnetic property to navigate along the earth’s magnetic lines. The bacterium derives its magnetism from ingesting iron. Once in its system the iron interacts with a protein producing a magnetic mineral called magnetite.

Once they understood how the Magnetsopirilllum magneticum worked its magic, the team figured out how to replicate this process outside its body.

They coated a surface in gold and added the protein in a chessboard pattern. When the surface is dipped in an iron solution, those squares covered with the protein start producing nanocrystals of magnetite. Each square covered with nanomagnets can store one bit.

The research is still at an experimental stage. The squares are 20 micrometers wide, that’s 2000 times larger than magnetic bits in conventional hard drives. But Staniland is confident they can bring the size down.

It is not just the problem of the fast approaching miniaturization limits of silicon-based electronics the researchers are hoping to solve. They’re looking to radically change the future of electronics. ‘Our aim is to develop a toolkit of proteins and chemicals which could be used to grow computer components from scratch’, Staniland said.

For more information: Leeds.ac.uk

Read full article

Hide full article

Discussion (0 comments)