Cheer up: the world has plenty of oil

Why the oil industry has buried the idea of "peak oil"

Cheer up: the world has plenty of oil

It's widely believed nowadays that global oil production is running up against its limits. "The days of easy oil are over", we are told and we should brace ourselves for an age of relative oil scarcity. The reality, however, is very different. As more and more people within the oil industry have come to realize in recent years, the world has plenty of oil that can be produced at competitive prices for a long, long time to come. This means the world does not face inevitable "energy poverty" and there is no reason to be afraid of unavoidable "energy wars".

|

| 'Oil demand will peak long before supply' (photo: Oil Shock Horror Probe) |

Four years ago, I wrote in my book The Myth of the Oil Crisis that: "To believe in imminent peak oil requires an unlikely concatenation of overstated reserves, the funnel of major projects drying up, the end of significant reserves growth, very disappointing exploration results, in both well-established and frontier basins, and a failure, despite ideal circumstances, of unconventional oil to deliver what has already been shown to be achievable."

I believe that what we have learned since then only confirms this assessment. Despite Total chief Christophe de Margerie's stating in 2010 that global production would be unlikely to exceed 100 million barrels per day (bpd), and that 90 million would be "optimistic", in November 2011 supply actually reached 90 million bpd for the first time ever. This is on a broad definition - including unconventional oil, natural gas liquids and biofuels - but to the consumer, the source of the fuel that goes into the tank is irrelevant.

True, spot prices have remained stubbornly high, driven last year by economic recovery and the disruption in Libya, this year by fears over Iran. But long-dated futures prices below $100 per barrel imply the market expects a longer-term easing.

In this article I will not undertake an exhaustive re-examination of the peak oil theory and its counter-arguments, but I will attempt to assess the lessons from the roller-coaster of the oil market of the last four years. I will discuss four areas in which key evidence has emerged explaining recent oil history and supporting a broadly optimistic view on our oil future: OPEC policy; new exploration plays and advances in unconventional oil; the reaction of the economy to oil shocks; and geopolitics, particularly in the world's oil hub, the Middle East.

OPEC policy

|

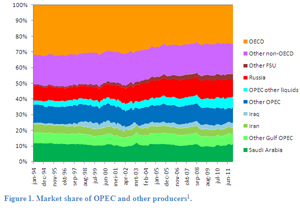

| Figure 1: Market share of OPEC and producers1 (click to enlarge) |

During this time, changes in Saudi Arabia's oil production correlate well with those of its Gulf OPEC allies Kuwait, the UAE and Qatar, but much less with those of other OPEC members and not at all with Russia's production pattern. (Nor does it correlate with neighbour Oman's production, showing that it is specifically Gulf OPEC - and not wider OPEC or the Gulf Arab countries - that matters.

This is because various external factors (war, sanctions, political instability and mismanagement) affected Saudi Arabia's major OPEC competitors - Iran, Iraq, Venezuela, Libya and Nigeria - during this period. As a result, and combined with shrinking spare capacity due to fast Asian demand growth, Saudi Arabia was able to enforce OPEC discipline - in stark contrast to the period 1986-1998. Under reasonable assumptions, OPEC maximises its (future) revenue by doing no more than maintaining its current market share2.

Numerous commentators have cast doubt on the size of OPEC's reserves, claiming them to be overstated, though without firm evidence. A study from consultancy IHS Energy from 20073 suggests a modest degree of overstatement, perhaps around 7% (~60 billion barrels). This is, however, more than compensated by IHS's view of underestimates outside OPEC, and Iraq's subsequent reserves upgrade (which is entirely plausible in view of renewed field studies, development and the arrival of modern technology after 30 years of war and sanctions).

In any case, it is clear that OPEC's output is nowhere near being constrained by reserves, even if these are overstated: its reserves-to-production ratio is more than 85 years, compared to 21 in Russia - where production is still growing, by a respectable 1.6% in the year to March.

The key OPEC news since 2008 was Iraq's award of massive field development contracts to international oil companies, which would bring production capacity to a nominal 13.5 million bpd around 2017. This target will not be reached, for a variety of logistical, economic, political and security-related reasons. But even an increase to 6.5 Mbpd would meet more than half the world’s incremental demand over that period.

After a long period of post-invasion decline and stagnation, the new investment is beginning to deliver: Iraq’s exports in March were the highest since 1989. It will probably exceed its 1979 record production this year or next, in the process overtaking Iran as OPEC's second-largest player.

In response to the Libyan and Iran crises, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia have also increased production to record highs, not matched in Saudi's case since 1980; in Kuwait's since 1973. Saudi Arabia's

| Repeatedly we hear that somewhere is "oil's last frontier". But there is always a new frontier. |

The implication that OPEC (led by Saudi Arabia) sought to maintain a fairly constant market share from 1994-2011 suggests four scenarios for the future:

- Non-OPEC production remains weak, leading to a continuation of OPEC's matching policy, and high prices to ration demand. Note though, that with an actual peak and decline in non-OPEC supplies, it becomes optimal for OPEC to increase market share

- Robust non-OPEC output growth resumes, forcing OPEC to match it to maintain market share, or as in the early 1980s, to cut output to defend an ultimately unfeasible price target

- OPEC changes its policy and begins increasing market share because it is worried about demand destruction or non-oil technologies

- Other OPEC members seek to expand capacity, most likely Iraq but possibly also Libya and a post-Chavez Venezuela, forcing Saudi Arabia and its Gulf allies to respond with increases of their own

These scenarios present a far more nuanced view of global oil production trajectories than the simplistic "peak oil" view of a resource-limited production curve.

Revival in exploration

Repeatedly we hear that somewhere is "oil's last frontier" - a title bestowed this year alone on Iraqi Kurdistan, the Arctic, East Africa and offshore Namibia. But there is always a new frontier.

In recent years, several significant new oil plays have emerged: Kurdistan; the West African Transform Margin (Ghana, Liberia, Sierra Leone, etc), its correlative in South America (French Guiana), East Africa (Uganda, Mozambique and now perhaps Kenya, plus major gas in Tanzania), and possibly offshore Sri Lanka and the Falklands. After many disappointments in the Arctic waters of Norway’s Barents Sea, two substantial oil finds have come along in the last year and demarcation of the border with Russia opens up another 80 000 km2 of Norwegian waters for exploration.

Adherents of the peak oil theory have often pointed out that since 1980, new finds failed to replace production. Despite this claim, reserves rose every year with the assistance of upgrades and improved recovery in existing fields. But in any case this disappointing exploration trend was reversed in 2010, when some 50 billion barrels of oil were discovered, enough to replace almost two years of production. In reality, high oil prices and new technology were always likely to lead to a revival in exploration. With low oil prices and abundant reserves through the 1980s and 1990s, there was simply no need for major exploration efforts.

Almost half of this new oil was found in Brazil, continuing the successful run of the deep-water "pre-salt" play in the Santos Basin. A study by an ex-Petrobras geologist suggests that even at conservative recovery factors of 25-30 percent, the pre-salt holds at least 123 billion barrels, more than twice government estimates.

With expectations that the pre-salt play may extend from Brazil across the Atlantic to once-conjoined Africa, the first pre-salt discoveries in Angola were made in January and February. Gabon and Congo are also promising.

As expected, peak oil advocates have focused on the difficulties of the pre-salt resources - the deep water, deep reservoirs, and difficult drilling conditions. Brazil’s state oil firm Petrobras, pioneer of the

| "The peak oil debate has lost a great deal of its relevance in the past three years" |

Mature areas have achieved some surprising successes too. Sverdrup, Norway's new discovery in the southern North Sea, is probably the third-largest field ever found in the country, in an area thought to be mature. Once they come onstream, Sverdrup and the new Barents fields should reverse Norway’s production decline, at least for a few years.

Growth in unconventionals

Antonio Brufau, the CEO of Spanish oil producer Repsol, told the World Petroleum Congress in Doha in December, "The speed at which technology changes and its consequences have taken us largely by surprise. The peak oil debate, for example, has lost a great deal of its relevance in the past three years".

The key issue driving Brufau's confidence was the extension of hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling techniques, the cornerstone of the US’s shale gas revolution, into 'tight' oil production. With these technologies it is possible to exploit low-permeability reservoirs which would otherwise not flow oil at commercial rates.

It has been clear for many years that 'unconventional' oil from a variety of sources greatly outweighs 'conventional' oil in volume. The issues have been cost, speed and environmental impacts. Reuters columnist John Kemp observes that "As a practical matter, the supply of liquid transportation fuels is unlimited at prices of $100 per barrel", pointing to the potential of gas- and coal-to-liquids.

Unconventional oil has progressed significantly over the past decade:

- Biofuels grew by 20% annually to reach almost 1.2 million barrels of oil equivalent per day by 2010. The world's first commercial-scale cellulosic biofuel plant is due to open in Italy this year, with costs of around $95 per barrel of ethanol. Abengoa, BP, Shell, DuPont and DONG will launch further facilities over the next two years.

- Shell opened the world's largest gas-to-liquids (GTL) plant in Qatar in 2011, with 140,000 bpd capacity, following South African synthetic fuels specialist Sasol's 34,000 bpd plant in the same country. Now both Shell and Sasol are planning GTL plants in the US to take advantage of low gas prices, with a total of 225,000 bpd under construction or consideration. Small-scale GTL for flared or stranded gas is also making progress.

- Operations began at Shenhua's 20,000 bpd coal-to-liquids plant, China's first commercial facility.

- Canada's oil sands production grew by some 85,000 bpd each year to reach close to 1.5 million bpd by the end of the decade, and is forecast to reach 3 million bpd by 2020.

Most striking is the breakthrough in tight oil production from shales and other low-permeability rocks. The Bakken in North Dakota and Montana is the most famous of these tight oil plays. In 1995, the United States Geological Survey estimated 151 million barrels could be extracted from the Bakken. In 2008, following successful wells drilled by EOG, the USGS dramatically increased its estimate, to 3-4.3 billion barrels. North Dakota forecasts it could ultimately recover 11 billion barrels, and Jeff Hume, president of Continental Resources, a major operator in the Bakken play, estimates 24 billion. It is, incidentally, interesting that the USGS, often accused by peak oil advocates of biasing its estimates of exploration potential upwards for unspecified political reasons, has been so conservative on shale oil.

|

| An oil rig in North Dakota atop the Bakken Shale Formation (photo: Indian Country/ Continental Resources) |

In March this year, North Dakota, previously insignificant, became the third-largest producing state in the US, at 546,000 bpd, ahead of California and behind only Texas and Alaska; it also overtook OPEC's smallest member, Ecuador. Planned projects could take output to 1.1 million bpd. In April, the US as a whole reached its highest output for 12 years.

Canada is already producing 160,000 bpd from its portion of the Bakken in Saskatchewan, and other tight oil projects. Western Canadian light oil production had displayed a reasonable Hubbert curve of the type beloved by peak oil advocates, with steady decline of around 3 percent per year - but since 2006, output has been kept stable by tight oil.

The US was the largest contributor to global supply growth in 2011 - an additional 320,000 bpd outweighed the whole of OPEC. Canada came second. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) in the US projects this pattern will be repeated in 2012. Jim Hackett, chairman and CEO of Anadarko Petroleum, has suggested that North American oil output could double over the next 25 years – probably an over-ambitious goal but one which would make the continent at least self-sufficient. Citigroup estimates that by 2022, the US could be producing 3.5 mbpd and observes that, "The concept of peak oil is being buried in North Dakota...We expect industry expectations to lag behind reality, just as they did with shale gas for many years".

The wide range of US tight oil in geographic location, geological age, rock type and tectonic style shows it is not a fluke - similar formations can be expected worldwide. And indeed, Brufau was touting his company’s Vaca Muerta discovery in Argentina, now thought to hold almost 23 billion barrels. Because of such finds, he observed that, "The possibility that usable resources under commercially viable terms will run out is no longer a concern in the short or medium term".

Even a country like France could become an oil producer. The Paris Basin may hold 5-10 billion barrels, enough to cover France's consumption for 10 years or so, but its exploitation is on hold due to France’s ban of hydraulic fracturing. Peak oil advocates will no doubt seize on this as evidence that the shale oil boom will be halted by environmental concerns. But it is more likely that as long as oil prices remain high, the spectacular success in North America will persuade most countries to exploit their resources, under strict safeguards. Russia's subsoil agency forecasts that output from the Bazhenov Shale in West Siberia could reach 1.7 million bpd by 2030. Other promising tight oil formations are known in Australia, the Santanghu Basin in China's Xinjiang region, the northern Gulf (Kuwait, Iraq and Iran), Abu Dhabi, Syria, Egypt, Colombia and elsewhere.

The utility of hydraulic fracturing is not limited only to shales. Old onshore fields in the US, such as West Texas's Permian Basin, have already seen a revival in production. One obvious implication, not yet widely drawn, is that the similar carbonate reservoirs of the Middle East should have vast potential for additional reserves. Formations such as the Mauddud in Kuwait and Iraq, Bangestan in Iran and Jubaila and Hanifa in Saudi Arabia, have been less-exploited to date because of their poorer quality compared to the main producing reservoirs.

Of course, these advances in unconventional oil have not been without problems. Despite improvements in practices, Canada's oil sands are facing growing environmental opposition. Both the oil sands and coal-to-liquids have unacceptably high carbon footprints in the longer term, unless carbon capture and storage is widely implemented.

Biofuels have run into trouble over increasing food prices and disturbance to virgin forests, and 'second-generation' biofuels from cellulose have made disappointing progress. The US has cut advanced biofuel production targets from 12 million barrels annually to just 0.2 million. Nevertheless, it is clear that unconventional oil in totality can grow fast enough at acceptable costs to reverse declines in conventional production.

Rising costs and the 'end of easy oil'?

Costs for unconventional resources are often thought to be much higher than for conventional fields. This is partly true, partly untrue, partly a misconception.

The untruth is found in some unconventional plays where the technology has been cracked. At $85 per barrel oil prices, Canadian tight oil plays are highly attractive, with rates of return of 30-70 percent. Costs for the Vaca Muerta are put at $30 per barrel. While relatively expensive compared to core OPEC countries’ costs, these are obviously far below current oil prices.

The misconception lies in the great run-up in costs that has occurred since the early 2000s: between 2004 and the third quarter of 2008, upstream capital costs as measured by energy consultancy CERA increased by 110 percent. This is often taken as evidence for the 'end of easy oil'. However, there are four underlying factors at play here that have nothing to do with geological depletion.

The first is a rise in input costs - steel, copper, cement, engineering contractors and so on - driven by the boom in China. These costs may stay high, but they may also fall back if the Chinese economy falters or miners and contractors eventually catch up with demand. Upstream costs dropped sharply during the global economic crisis and are still just below their 2008 peak.

The second is that high oil prices themselves drive rising production costs. Projects which were simply not viable at $20 per barrel become attractive at $50 per barrel, dragging up average reported costs.

The third is that many of these unconventional projects are pioneering new technology. Shell's Pearl gas-to-liquids plant, budgeted at $5 billion in 2003, started production in June 2011 at a final cost of $18-19 billion.

We should have expected this phenomenon. As observed of another new frontier oil play, "Initial cost

| "As a practical matter, the supply of liquid transportation fuels is unlimited at prices of $100 per barrel" |

But these costs fall again once the technology is mastered. For comparison, Buzzard, the most recent large UK discovery (2001), had development costs of some $3000 per barrel per day in 1972 dollars, even though it is smaller than Forties and contains heavier, harder-to-produce oil. The time taken to drill and complete a Bakken well has fallen from 65 days in 2008 to 25 days last year.

The fourth factor is the rents that accrue to scarce factors of production6. In the case of resources with effectively unrestricted access, such as gas for LNG in Australia, or oil sands in Alberta, competition for limited resources - drilling rigs, compressors, natural gas, water, geologists, engineers - ensures that excess returns are dissipated to service providers and personnel. Governments take the opportunity to raise tax rates and royalty rates. Oil companies themselves earn only barely acceptable returns.

To return to the example of the early days of the North Sea, "In 1976 the average cost of an exploration well was £3.5 million, in 1980 it was £7 million and in 1985 it was over £9 million"7. The break-even price for oil-sands appears to have risen from some $25 per barrel in the late 1990s to $75-$90 today. Yet the resource has not changed, while technology has advanced markedly.

The combination of new technologies and scarcity rents has led to several disappointments and the phenomenon of receding horizons, as technologies that were marginally economic at $20 per barrel oil prices remain marginal at $80. This is not unique to unconventional oil, but has bedevilled nuclear power and some renewables.

Yes, if the oil price were to fall, the pace of unconventional developments would no doubt slacken off, but the break-even price would fall back – as it did after the 2008 economic crisis, when Shell saw new oil sands projects as economic at $50 per barrel.

Peak demand

It has been increasingly clear that OECD demand, which topped out just short of 50 million bpd in 2005, is in long-term decline, punctuated by occasional reversals as in 2010. This is driven by high oil prices encouraging efficiency; economic troubles; ageing populations; and environmental policies which will probably bite increasingly in the future.

UK oil consumption has fallen 18% since its 2006 peak (which was itself lower than the 1973 all-time high), while despite the recession the economy has still grown overall.

With the first stirrings of recovery, the US responded to high oil prices with a leap in oil efficiency, which grew by 3.7 percent in 2011. Consumers are buying significantly more efficient vehicles, while driving distances have increased little from the depths of the recession. With a culture of big cars, limited public transport, minimal dieselisation and cheap natural gas, the US has more room than Europe for further oil savings.

Non-OECD demand continues to grow strongly, driven by China above all, with strong contributions from the Middle East and other Asian tigers. But there are factors working to limit this growth. First, it could be interrupted by an economic slowdown in the Middle Kingdom. Then, China and India have been gradually reforming (i.e. increasing) fuel prices, which at least for petrol now exceed US prices. China's fuel-efficiency standards are also significantly tougher than in the US, and it offers significant support for hybrid vehicles.

With regard to electric cars, efficiency and incremental improvements remain key. It has proved much harder than many anticipated to develop affordable, practical electric vehicles - the same disappointment that has befallen other innovators in the slow-moving, capital-intensive energy industry. Yet several production models of plug-in hybrids are now available, even if they remain expensive. Deutsche Bank forecast in 2010 that plug-in hybrids would be half of China's vehicle fleet by 2030, and that the take-up of alternative vehicles would lead oil demand - not supply8 - to peak at 93 million bpd in 2022.

Of course oil is still king in road and air transport. But there remains substantial room to displace it from other uses. Shipping consumes some 8-10 mbpd; there is increasing attention to LNG-powered ships, with nuclear engines plausible in the longer term. 5 mbpd of oil is still burnt in power generation and could be replaced entirely. Petrochemical demand can be substituted by gas, biomass or even coal feedstocks.

Domestic oil use in several major oil exporters is rising fast, driven by strong economic growth under the stimulus of petroleum revenues; diversification into energy-intensive industries; fuel subsidies; and growing populations. This has led peak oil proponents to devise the 'export land' model, by which stagnant production conspires with consumption at home to produce a sharp drop in exports. This seems to be observable in the case of Saudi Arabia, for instance, which burns some 1 million bpd of crude oil in summer for power generation.

But this trend should not be simplistically extrapolated to predict a collapse in exportable oil generally. Gulf producers are increasingly aware of unsustainable domestic consumption trends, and are

| Even a country like France could become an oil producer. The Paris Basin may hold 5-10 billion barrels, enough to cover France's consumption for 10 years or so |

At the end of 2010, Iran carried out a dramatic subsidy reform, previously thought politically impossible, replacing fuel and electricity handouts with direct cash payments. Consumption fell by 4-5% in the following year. The UAE also raised petrol prices twice in 2010. Though concerns over the Arab revolutions, and political protests in Nigeria, have deterred subsidy reform elsewhere, price rises and improved efficiency are clearly on their way.

Finally, there is an obvious negative feedback loop in oil exporters’ domestic consumption. High oil revenues drive economic growth; if exports fall, so does growth and hence oil use. It is plainly inconceivable that a Saudi Arabia which had ceased to be a major oil exporter could be consuming 5 mbpd or more itself. To the extent that oil and gas are used domestically for export-oriented industries such as petrochemicals, they are simply replacing consumption elsewhere.

Geopolitical implications

The usual gloomy prognostications from the likes of Michael Klare, who is predicting a new era of "resource wars", have not yet been borne out. Market-based competition has so far proved a more attractive and effective method to obtain oil than 'securing' it by military means. The rising Asian economies have been able to meet their energy needs at prices which, although high, have certainly not choked off growth. Developed countries have been able to rely on increased efficiency and, in the case of North America, domestic production. There are areas of geopolitical competition, such as the South China Sea, but issues in the Arctic are being resolved by negotiation, as with the Norway-Russia border demarcation. All the major powers bar India have secured oil contracts in the new Iraq by normal commercial processes; and Chinese companies are now investing heavily in North American petroleum.

The political situation in the Middle East, still the heart of global oil supply, has been transformed over the past year, leading to one major oil disruption, in Libya, halts to exports from of lesser producers in Yemen and Syria, and concerns, probably overblown, over the security of the big fields in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province. Separately the dispute between Sudan and the new nation of South Sudan, and the confrontation over Iran’s nuclear programme, have brought further real or threatened interruptions.

|

| (c) Noah Musser/ Washington University Political Review |

Practically, the Iranian threat to the Strait of Hormuz, which resurfaces at irregular intervals, is overstated. On the wider scene, the consequences of the Arab revolutions are still unfolding. But in a region that has seen four major wars and associated oil shocks in the last thirty-five years, it seems odd to argue that greater political freedom must mean reduced energy security.

Climate

The realisation that oil (and even more, gas and coal) resources are abundant, if not always easy to extract, clarifies the climate debate. It has been suggested by some that peak oil would bring economic collapse before severe climate change strikes; by others that the crises would arrive at similar times and reinforce each other; by yet others, such as James Hansen9, that peak oil would worsen climate change by forcing a switch to high-carbon alternatives.

Now it seems likely that none of these things will occur. Coal remains the key climate villain. But coal and gas in electricity generation and industry are amenable to carbon capture and storage, or can be replaced by renewables and nuclear power. Using as transport fuels a large portion of 2 trillion or more barrels of recoverable oil will make it impossible to achieve targets of keeping atmospheric carbon dioxide below 450 ppm.

Unless we develop methods of removing CO2 directly from the atmosphere, either biological or technological, this observation further strengthens the case that peak demand will arrive long before peak supply - as curbs on emissions encourage electric vehicles, advanced biofuels or other expedients.

The Intellectual Climate

Yet these dramatic developments and advances in our understanding appear to have been ignored by many observers, who remain trapped in a paradigm where physical availability of resources is the only significant factor.

Former UK Chief Scientific Adviser, David King, with oceanographer James Murray, published an essay in Nature10 in January arguing that there has been a peak in 'easy access' oil (whatever that means) since 2005. Remarkably, this study mentions neither OPEC policy (including its 2008 production cuts in response to the economic crisis); Iraq, with its enormous volumes of 'easily-extracted' oil; nor shale oil.

Intellectually, the peak oil movement appears to have moved on to preparation for collapse (or at least an end to growth). Peak oil has become conflated with other real or potential crises: the recession, climate change and overpopulation.

This is very reminiscent of the 1970s, and indeed features of OPEC strategy, rising costs, new resource types and technologies are also familiar. There are clearly different ways the oil market may evolve over the next five to ten years. A continuation of high prices in the face of production disappointments and strong Asian growth is plausible. So is a kind of re-run of the 1980s, with new supplies, growing efficiency and intra-OPEC competition driving down prices. What is not on the horizon is a resource-limited peak in production, nor an associated economic collapse.

|

About the author Robin M. Mills is Head of Consulting at Manaar Energy (Dubai), and author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis and Capturing Carbon. robin@oilcrisismyth.com and Twitter @robinenergy |

1 Data from US Energy Information Administration

2 D. Gately (2007) 'What oil export levels should we expect from OPEC?' The Energy Journal, Vol.28, No.2

3 Petroleum Intelligence Weekly (2nd April 2007), Vol.XLVI, No.14

4 Peter Johnson (1988) 'The Structure of British Industry', HarperCollins

5 J.E. Hartshorn (1993) 'Oil Trade: Politics and Prospects' Cambridge University Press

6 For this point, I am indebted to Andrew Leach of the University of Alberta.

7 Peter Johnson (1988) 'The Structure of British Industry', HarperCollins

8 Obviously supply will equal demand - but the peak will be driven by competitors to oil, not limits to production.

9 Kharecha, P.A., and J.E. Hansen, 2008: Implications of "peak oil" for atmospheric CO2 and climate. Global Biogeochem. Cycles, 22

10 'Oil's tipping point has passed' (26th January 2012), J. Murray and D. King, Nature, Vol.481, p433-435