EU struggles to phase out coal subsidies

EU struggles to phase out coal subsidies

The European Commission wants to extend the aid regime for Europe’s coal sector, which is set to expire at the end of the year, for another decade. In a proposal for a new regime, Brussels puts more emphasis on the need to close unprofitable mines. But environmental organisations and some European commissioners say this does not go far enough. They argue that an extension of aid flies in the face of the EU’s climate policy. What complicates the issue that it is not just about climate or the envirionment – but about employment and security of supply as well.

|

| Lignite mining in Germany. Photo: RWE |

The current EU aid regime for the coal sector terminates at the end of 2010. If no new framework is put in place, state aid for hard coal will come to fall under the general rules for state aid, which are much stricter than the present coal subsidy regime. In that case, state aid is likely to be forbidden or curtailed. This will lead to the immediate closure of the large number of hard coal mines whose factory costs are well above global coal prices. That would result in up to 100,000 job losses. Most of the impact would be felt in a limited number of regions, mostly concentrated in Germany, Spain and Romania.

The European Commission is expected to come up with a proposal for a new regime on 21 July. According to draft documents, Brussels is likely to propose a new Regulation that would allow Member States to grant aid aimed at covering production losses, but only if they agree to wind down current activities and come up with well-defined mine-closure plans. The aid would have to be gradually phased out over a period of 10 years. The Regulation would also allow Member States to grant aid for the social and environmental costs linked to the closure of coal mines, such as social welfare benefits and costs related to the rehabilitation of the former coal-mining sites.

This is not a radical departure from the current regime, which also mandates gradually diminishing aid, but unlike the present regime, it does emphasise the need to close unprofitable mines. It also closes certain loopholes, such as security of supply considerations which Member States were able to use as justification for continuing subsidies. It should be noted, though, that this is merely a draft proposal and that it is possible that the final proposal on 21 July might be a different one.

Sensitive dossier

Until recently, state aid for hard coal came under the remit of the EU’s Energy Commissioner, but earlier this year European Commission President Barroso transferred the coal state aid dossier to the EU’s Competition Commissioner. This decision was part of Barroso’s efforts to streamline the Commission’s work during his second term. As it happens, the new Competition Commissioner, Joaquin Almunia, is Spanish, which is significant because the coal sector in Spain relies heavily on public subsidies. That makes this a very sensitive issue in Spain. Ironically, the current European framework for state aid for hard coal is one of the important legacies of another former Spanish commissionner, Loyola de Palacio, who was Energy Commissioner from 1999 to 2004.

|

| The coal industry provides 280,000 jobs in the EU. |

Almunia has already had to face up to his colleagues in the European Commission, in particular the EU’s Climate Change Commissioner Connie Hedegaard and the EU’s Environment Commissioner Janez Potocnik. They do not see how extension of the aid regime fits in with the promises to move to a low-carbon economy.

Power plants

One of the arguments put forward by the European coal industry, represented by the European Association for Coal and Lignite (Euracoal), for the extension of the aid regime is that ‘access to coal deposits’ should be kept ‘open as much as possible’ for security of supply reasons. However, in its draft proposal for a new Regulation, the Commission indicates that it does not want to take this consideration into account. The Commission says that subsidised coal’s contribution to the European energy mix is ‘small’, just over 5%. When only the coal is taken into account which receives aid to cover production losses, this figure falls to just 1.4%.

Currently some 18% of the electricity produced in Europe comes from hard coal and 58% of that coal is imported. A little over two thirds of European production is subsidised. According to the Commission, almost 100% of the subsidised production would disappear if aid were to be cut off. It would be easy to resort to using imported coal because statistics show that there is no supply problem at the global level. The effect on prices of a collapse in the European production of subsidised coal is regarded as minimal, given that it only accounts for 4% of the volume of world trade, well below the 7% growth rate of world trade in coal.

However, on the local level, the situation may be different. There is a strong correlation between coal’s share in the energy mix of a country and its possession of coal resources. Also in many places big coal power stations sit side by side with the mines. Industrial associations have pointed out that these coal-powered power stations cannot easily switch from indigenous coal to imported coal without substantial modifications of the power station and of the adjacent infrastructure. Coal-fired power plants, which have been designed to burn coal of a given quality – such as coal from a nearby coal mine – cannot always easily be adapted to other coal types. This concerns mainly the coal mills, as imported coal is usually not supplied in a properly treated state while indigenous coal is often already prepared in the coal mining company. If the mine providing the coal were to be closed, the transformation of the burners and the adaptation of the transport infrastructure may require significant investments which the station would not always be able to afford.

For example, the Hungarian Power Companies Ltd and Vertési Power Plant Ltd indicate that stopping aid for the only Hungarian coal mine would lead to the closure of the Vertési power plant. If the mine were to be closed, the power station’s boilers would need to be technically modified, but, even after this modification, they would not be as efficient as a modern power plant. Furthermore, imported coal could only be transported by rail, increasing its cost. Still, subsidised coal accounts for only 3.6% of Hungary’s national power generation.

The Industrial Development Agency in Poland estimates that the modernisation of Polish power stations required by a switch to imported coal would take between 15 and 20 years. It also notes that transport infrastructure (ports and roads) is limited and that, because of its geographical location, Poland would be mainly dependent on coal from its eastern neighbours. However, as far as the impact of the regulation on state aid for hard coal is concerned, Poland is not really affected as it does not need to subsidise its coal.

At any rate, the Commission concludes that ‘it is doubtful that this problem would be of such a magnitude as to cause security of supply problems either at EU or national level’.

Unfortunate problem of coherence

On 22 June, the EU’s top civil servants, European Council President Herman van Rompuy and European Commission President José Manuel Barroso sent a letter to G20 leaders ahead of their summit in Toronto four days later. In the letter, the two European leaders gave assurances that ‘the European Union also supports the process to rationalise inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, which will improve energy efficiency, enhance energy security and contribute to the fight against climate change and to fiscal consolidation’. Just days later, proposals to continue with the European hard coal aid regime were leaked in the press.

Critics were quick to react. ‘I just can’t understand it at all’, says Claude Turmes, a prominent “Green” Member of the European Parliament. ‘How can Mr Barroso want to fight to phase out subsidies for fossil energies at the G20 level and at the same time come up with an EU proposal that would extend these subsidies? I only hope that this unfortunate problem of coherence will be quickly resolved and that this extension will not go forward. The credibility of the European Union is at stake.’ According to WWF, ‘the Commission must avoid widening the credibility gap between our climate rhetoric and our climate actions.’

|

| Coal mining has a considerable impact on the immediate environment. Here open cast mining in Germany. |

In addition to its impact on the climate, coal mining also has a considerable impact on the immediate environment, in the form of air and water pollution and loss of biodiversity in water-based ecosystems. Closing coal mines would therefore have a positive impact on local environments, particularly if closed sites are properly cleaned up. Commissioner Almunia’s proposals explicitly state that costs from cleaning up coal mining sites would be eligible for state aid. Critics have pointed out that if such costs are borne by the taxpayer, it would blatantly contradict the ‘polluter pays’ principle underpinning European legislation.

A long-haul process

Clearly, extending European aid for coal would help save jobs and the economic fabric of whole regions where the mining industry is one of the main industrial activities. ‘Experience with economic and regional restructuring has shown that the labour market can more easily absorb the laid-off work force if the lay-offs are spread over time,’ says the Commission. The German coal mine closure plan is exemplary in this respect as it runs until 2018. This makes it possible to reduce the production of uncompetitive mines while minimising the number of direct lay-offs and maximising accompanying measures allowing the work force to switch to other activities.

The International Labour Organisation is also in favour of gradual closures. ‘Sudden closure in an area that is heavily dependent on a mine will have a major and, quite possibly, lasting adverse economic impact on the local economy, even in a generally robust national economy, whereas phasing out smoothly will tend to have less of an impact.’ Experience shows that restructuring an industry in mining regions is very difficult. The sudden closure of coal mines, which leads to huge numbers of people being laid off, puts heavy pressure on the regional labour market. The result is that many mine workers remain unemployed for long periods of time and therefore tend to become less employable. Potential investors in new activities are scared off by the decline in activity in the region.

The coal industry provides 280,000 jobs in the EU, according to Euracoal. For each job in the mining industry, there are 1.3 ancillary jobs. While unemployment figures would only be marginally affected at the national level by a closure of uncompetitive mines, impacts at the local level could be considerable, leading to unemployment rates of 50% in some areas. The most affected regions would be Münster and Saarland in Germany, Asturias in Spain and Vest in Romania (Jiu Valley).

Environmental NGOs maintain that lots of jobs could be transferred to the renewables sector and that the mines can be closed in a few years. But there is no certainty that the renewables sector can take over from the coal sector in the same regions. ‘Regional restructuring is a long-haul process that takes decades rather than years,’ warns the Commission.

The industry has one final argument for not closing coal mines too hastily: coal prices could rise in future, which would make some mines become competitive again. ‘A hasty closure of hard coal underground mines based on short-term considerations was, for example, the wrong decision to take in many cases in the long run. Some mines in the UK and Poland, which closed prematurely, would now be able to produce coal at competitive prices.’

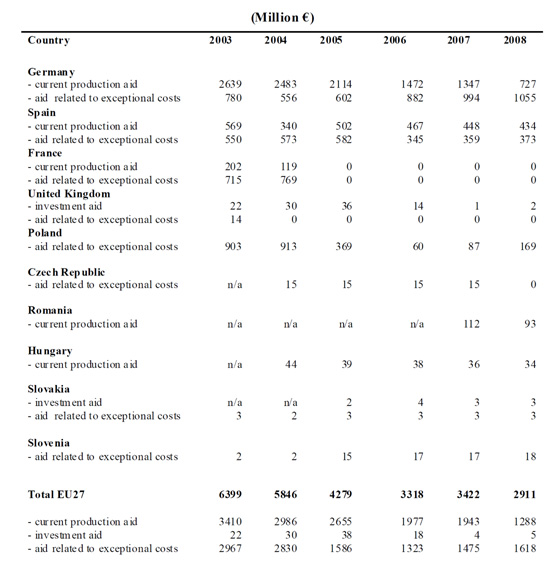

| State Aid 2003-2008 - amounts actually granted by Member States or authorised by the Commission for the relevant year (Please click on the image for a larger PDF version) |

|