A giant comes to life in the deserts of Qatar

on

A giant comes to life in the deserts of Qatar

Imagine a technology that could take natural gas and turn it into premium oil products, such as low-sulphur vehicle fuels, petrochemical feedstocks and high-quality lubricants. In today's era of cheap abundant gas and worryingly expensive oil it would be like turning water into wine. This technology not only exists, but is being implemented at massive scale in the deserts of Qatar by Shell. Having invested $19 billion in constructing this modern-day wonder of the world, Shell is in the process of starting it up. Alex Forbes visited Qatar to see Pearl GTL for himself.

|

| 2,500 systems are to be commissioned and operated by 50,000 workers |

Shell showed us how its Bintulu plant could turn natural gas produced offshore in the South China Sea into 14,700 barrels/day (b/d) of premium oil products and waxes. It also outlined big ambitions for up to four world-scale 75,000 b/d plants in locations as diverse as Indonesia, Iran, Egypt and Trinidad. It seemed that - at long last - we were entering a promising decade for a technology invented as long ago as the 1920s but yet to make much commercial impact.

A decade on I am in Doha, capital of Qatar, waiting for a car that will take me to site of what - when ramped up to full output - will be the world's largest GTL project by far. At my feet is a black bag containing overalls, a hard hat, protective glasses, ear plugs, gloves and steel-capped boots. Shell takes safety seriously. Inside my jacket pocket are my passport and my pass to Ras Laffan Industrial City, location of the Pearl GTL construction site and the world’s largest agglomeration of natural gas-related industry. Not surprisingly, security is tight.

A gigantic plant

Shell's proposed projects in Indonesia, Iran, Egypt and Trinidad never did materialise. Instead Shell opted to build a gigantic plant in Qatar, which has the world's third-largest reserves of natural gas and has created one of the most welcoming business environments in the world for large-scale energy projects. Today is my first chance to see the steel and concrete result of the vision that Shell had outlined a decade earlier.

In 2002, when Pearl GTL was mooted, Shell's presence in Qatar consisted of an office staffed by one executive and a secretary. This was kind of ironic when you consider that it was Shell that discovered

| The site is as large as London's Hyde Park. The amount of concrete used to build it would be enough for 8 Wembley Stadiums |

Whatever else it may one day produce, Pearl is a world-class generator of superlatives. The site is as large as London's Hyde Park. The amount of concrete used to build it would be enough for 8 Wembley Stadiums. At peak construction the amount of steel needed each month would have been enough for 2.5 Eiffel Towers. If laid end to end, the tubes in its GTL synthesis reactors would stretch from Doha to Tokyo. At peak construction there were 50,000 workers on site. And so the list goes on . . .

For those in the energy business, however, its true scale can perhaps best be measured by how much product it will produce and how much cash it will generate. When ramped up to full output it will produce 140,000 b/d of GTL products, from two 70,000 b/d 'trains' and 120,000 b/d of liquefied petroleum Gas (LPG), a total hydrocarbons output of 260,000 b/d. In other words, around 7.5% of Shell’s hydrocarbons output last year.

Mind-boggling cash

The cash numbers are even more mind-boggling. At a final capital cost of $18-19 billion, Pearl is one of the most expensive energy projects ever built. When the project was first proposed in 2002, Shell estimated it would cost $4-5 billion. By the time of final investment decision (FID) in 2006, cost estimates had risen to $12-18 billion.

|

| Pearl village offers a community where 40,000 people get recreation opportunities, have places of worship and have a training centre |

To put it another way, Pearl will take gas that costs around $6/barrel of oil equivalent (boe) to produce and convert it into products that currently attract more than $100/boe. Nice work if you can get it.

Based on just crude price, these back-of-an-envelope calculations ignore refining margin and the premium that GTL products ought to be able to realise because of their exceptional qualities. The diesel fuel will be low in sulphur with a high cetane number, making it an excellent blend stock. The naphtha will be highly paraffinic making it an ideal feedstock for production of petrochemicals such as plastics. The kerosene has been approved for use in aviation fuel in a blend up to 50%. The normal paraffin will be used to produce detergents. And the base oils will be used to manufacture high-performance synthetic lubricants.

Despite the scale and complexity of the plant, Shell's CEO Peter Voser this week said the project was on track to start up its first GTL train by the middle of this year and the second before the year-end. He expects the plant to ramp up to full output by the middle of next year.

Purple tape, purple tape

Having cleared security at the entrance to Ras Laffan Industrial City, and been driven into the Pearl construction site, I'm shown into an empty office where I can change into the gear in my black bag. To my great delight it all fits. The day is a little overcast, unusual for Qatar, but a relief for me, as we set off to tour the plant.

The engineer accompanying me explains there are 2,500 systems to be commissioned. The process began in late 2009 and by now many of the systems are up and running, particularly in the noisy utilities section. All commissioned equipment has been festooned with purple tape to let workers know to keep away. As we make our way around the seemingly endless construction site, it's clear that the makers of purple tape have been doing brisk business.

There may be 50,000 workers on site but the atmosphere is far from frenetic. Gangs of workers, dressed in overalls of bright, obviously significant colours, make their way around in well-ordered columns. To ward off the desert heat, many have cloths around their faces, and it is in their choice of these that many choose to express their individuality. I note that one is a Jimi Hendrix fan.

|

| Aerial view of the Pearl GTL site |

One challenge posed by this contracting strategy is that it has created a lot of physical and contractual interfaces. How has the management of those interfaces worked out in practice? 'We designed this thing in 13 different offices in 10 different countries,' says Brown. 'As you’ll see at the site there's a lot of physical interfaces across the boundaries of those contracts. We haven't had any significant interface issue. The physical interfaces have worked out really well. It's the power of the modern computer-aided design (CAD) systems that allows you to knit the project together.'

The people challenge

I ask him about the challenges Shell has faced in building this gigantic project. 'We've built this project at one of the most overheated times, both globally, in the EPC (engineering, procurement and construction) world, but also locally within Qatar,' he says. 'We've imported 2 million freight tonnes of equipment and materials and no significant item of equipment has been late.'

'The second challenge was to get the people we need. Bringing them on board, some of them relatively inexperienced, training them up, and having them effective, has been quite an achievement.'

'One of the things that underpinned that is the way we have dealt with people. We have the Pearl Village

| 'We've imported 2 million freight tonnes of equipment and materials and no significant item of equipment has been late' |

How much of a model is the approach Shell has taken with the Pearl Village for Shell or indeed for other companies to learn from?

'It has become a model within the company but also within Qatar. By investing in people, you get the productivity, safety and quality that you look for. It’s something people have always remarked on. People are generally impressed with the Village and the sense of community they get.'

Village people

It's lunchtime, and for lunch I am taken to the Pearl Village, where much time and trouble has gone into ensuring people's welfare. The focus of the village is a park, with sports facilities and an outdoor cinema theatre. Introduced briefly to Viviane Sulkoske, who runs the welfare operation, and reports directly to the village's 'mayor', she sees I am rather hot and kindly offers me a baseball cap to keep the sun off. I am grateful. I am also amused by the choice of street names between the camps: Chestnut Drive, Acacia Drive and so on. And, by the way, lunch was excellent.

Will it work as planned?

In visiting Pearl GTL I cannot but help recall that I was the first journalist to visit Oryx GTL, Shell's neighbour at Ras Laffan, while that project was under construction. Then, as now, I felt a strong sense of witnessing the birth of a project that would play a key role in determining the future of the industry. Unfortunately for Oryx's sponsors - Qatar Petroleum and Sasol - the technology used in that project did not work as expected and it took three years for Oryx to get close to its full 34,000 b/d capacity.

I put it to Andy Brown that the GTL world - and others - will be looking closely at how Shell's technology performs as Pearl starts up. How confident is he that the technology will work? 'The basis of our

| Then, as now, I felt a strong sense of witnessing the birth of a project that would play a key role in determining the future of the industry |

Since its reconstruction a decade ago, Bintulu has shown exceptional levels of reliability and has become a big money-spinner for Shell. In 2008 alone it made over $200 million. The challenge with Pearl was always more around the complexities of project execution on such a large site, and Shell seems to have kept on top of that.

There has long been a debate around the relative merits of LNG and GTL, and with Shell Qatar heavily involved in both I ask Brown for his views: 'We're very pleased to be in both. It's a strong diversification opportunity. If you look, for instance, at the netback of GTL versus LNG - a molecule going into each plant, one ending up in the marginal market, being the US today, and the other going into GTL - the molecule going into the GTL plant is going to earn a lot more money for the resource-holder.'

What next?

At Shell's annual strategy presentation in London this week I asked CEO Peter Voser what plans the company has for future GTL projects, perhaps in the US where gas is abundant and therefore cheap, oil is expensive, and where there is widespread paranoia about overdependence on imported oil.

|

| Worshipping at Pearl village |

Meanwhile, the other major GTL technology company, South Africa's Sasol, has already made a move into North America. A few months ago it announced that it had agreed to take a stake in shale gas assets owned by Canada's Talisman Energy, with GTL being a potential monetisation option.

Nearly a century after two German scientists, Professor Franz Fischer and Doctor Hans Tropsch, were granted a patent for the process at the heart of the gas-to-liquids conversion, it seems the industry's time may at last have come. Market fundamentals have never looked better for the GTL industry; getting the technology to work remains the big challenge.

|

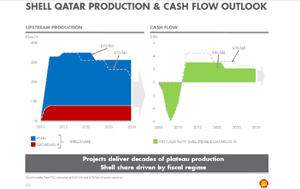

Shell Qatar production and cash flow outlook

|

Discussion (0 comments)