DOWN, BUT NOT OUT

on

The prospects for carbon trading post-Copenhagen

Down, but not out

The disappointing outcome of the Copenhagen climate change talks has led to questions about the future of the international carbon market. Failure to agree a post-Kyoto climate treaty has certainly dented confidence in the short term. But analysts and traders believe the carbon market is robust enough to survive even without such a treaty. A more fundamental question is whether carbon trading is an effective way of cutting greenhouse gas emissions. That debate is far from settled.

|

| For sale: 1 tonne of CO2 |

| Article Highlights: |

| - The disappointing outcome of the Copenhagen climate conference has created great uncertainty over the future of international carbon markets - Political developments in the US and Australia make it unlikely that national cap-and-trade legislation will be passed in those countries anytime soon. - The recession is also hurting the prospects for a growth in carbon markets. -On the positive side, many countries have unilaterally pledged to achieve significant emissions reductions. - As for the EU, its Emissions Trading Scheme is enshrined in legislation until 2020 and will continue to play a central role in European climate change policy |

Hopes were high that the climate talks at the United Nation’s 15th Conference of the Parties (COP 15) would help accelerate the development of carbon trading. But the hastily cobbled-together Copenhagen Accord fell far short of expectations. Even the UN official leading the negotiations, Yvo de Boer, described it as just a ‘political letter of intent’.

Policy vacuum

The outlook for carbon trading now looks much less optimistic. Analysts and traders doubt that the proposed federal cap-and-trade legislation in the US – seen by many as the holy grail of carbon markets because it would boost trading volumes – will be passed anytime soon. Australia’s proposed legislation has also run into political difficulties. Prices in Europe’s ETS have been depressed by the recession, while trading volumes in 2009 were artificially inflated by VAT fraud. And there is no doubt that the outcome of Copenhagen has depressed market sentiment and slowed political momentum, at least in the short term.

‘It was very hard to put a positive spin on what came out of Copenhagen,’ says Trevor Sikorski, director at Barclays Capital, an investment bank involved in carbon trading. ‘It’s just left a policy vacuum. Nobody’s really sure what’s going to happen. I would say the mood in the market is generally downbeat at the moment for a widening of the market and a deepening in the market.’

The view of Guy Turner, director of carbon markets at Bloomberg New Energy Finance, is that: ‘Copenhagen had a negative effect on the market because the market built up its expectations falsely about what could ever come out of that process. At New Energy Finance we never held any great hopes for the process. We always said that it would revert back to national policies.’

Climate scandals

On that front there is cause for optimism. For while the Copenhagen negotiations were themselves disappointing, the unilateral emissions reductions pledges that were made in the run-up to the Copenhagen talks were, says Turner, ‘not a bad outcome’.

‘Going into Copenhagen most of the developed countries made pledges. Europe had a target of 20% or 30%, Australia anywhere between 5% and 20%. Japan had 15%. The US had the Waxman-Markey legislation. The big developed countries or blocks were dealing with expectations. And without any negotiation, the targets were fairly similar. They were all coming out to be 15% reductions on 2005 levels by 2020.’ By the end-of-January deadline, 65 countries had submitted pledges of emissions reduction targets or Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions (NAMAs) for the two appendices that are part of the Copenhagen Accord. De Boer believes that ‘the world can expect them to honour those pledges’.

But the prospects for turning those pledges into functioning cap-and-trade legislation have taken a knock. That, says Turner, is partly because of the loss of political momentum following Copenhagen but also partly for other reasons.

One is the ongoing recession. ‘We’re looking potentially at a double-dip,’ says Turner. ‘The stimulus packages have really hurt government finances and budget deficits are looking pretty rocky. That is distracting governments and worrying voters. If you look at the opinion polls about people’s willingness to react to climate change, it’s falling because they’ve got other worries on their minds.’

Other factors that Turner cites include the recent climate scandals involving the University of East Anglia and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and the freezing weather that has gripped Europe and North America. ‘Washington’s under three foot of snow,’ he says, ‘and we had blizzards for the best part of a month in the UK and northern Europe. It’s hard to get your mind round climate change when there’s three foot of snow outside.’

Back seat

Events in Washington are being watched closely by the carbon trading community because of the huge boost to the market that a federal cap-and-trade scheme would bring. However, after the optimism of last year – following the passing of the Waxman-Markey bill by the House of Representatives and the introduction of the Kerry-Boxer bill in the Senate – the signs are not looking good.

‘A lot depends on what happens in the US domestically,’ says Endre Tvinnereim, senior analyst at Point Carbon, a consultancy firm. ‘That’s really the key.’ However, Point Carbon has downgraded the probability of a cap-and-trade bill being passed by Congress this year to just 20%.

At Barclays Capital, Sikorski too has lowered his expectations. ‘Last year we were fairly positive on the US developments. Now, the Kerry-Boxer bill seems to have been put on the back seat because the Republicans have said “No, we’re not going to support it”.’ And so John Kerry is trying to draft another bill with an independent, Joe Lieberman, and a Republican called Lindsey Graham. But no one has seen that bill, no one knows exactly what’s in it.

‘To get a bill out of the Senate this year would take a very big legislative push by all involved – and a lot of political will. I’m not sure we see that political will anymore. We’re resigned to possibly not seeing legislation before 2011, and we don’t even know what that legislation’s going to look like – if it’s going to be cap-and-trade. There are so many bills out there trying to do so many different things. It’s hard to get a good feel for how close we are to a [federal] cap-and-trade scheme in the US.’

It doesn’t help that that President Barack Obama is struggling to get health-care legislation through its final stages. Moreover, the Democrats have lost their 60-seat filibuster-proof supermajority in the Senate, following the election of a Republican in Massachusetts last month. There have even been reports quoting Obama as saying that the cap-and-trade elements of climate legislation might be separated out in order to get a bill passed that would promote jobs in clean energy.

Also significant is that the 2011 budget proposal recently released by the Obama administration does not contain projected revenue from a cap-and-trade system, unlike the 2010 budget. What the budget says is that: ‘The Administration will work to enact and implement a comprehensive market-based policy that will reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the range of 17% in 2020 and more than 80% by 2050’. There is no specific mention of cap-and-trade or emissions trading.

Guy Turner puts the chance of federal cap-and-trade legislation passing in the US at less than 25%. Though he adds: ‘That’s not to say you won’t get continuation of regional schemes.’ One such scheme, already up and running, is the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) in the north-east.

The prospects for cap-and-trade legislation in Australia, another important focus for the carbon trading community, have also receded. ‘Last year,’ says Sikorski, ‘we were pretty confident that in November the Federal Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme (CPRS) would pass – but it all fell apart at the last minute. They’re bringing it back this month but, if anything, the politics in Australia have got further away from getting that cap-and-trade bill passed than they were in November. So that’s now looking pretty unlikely.’

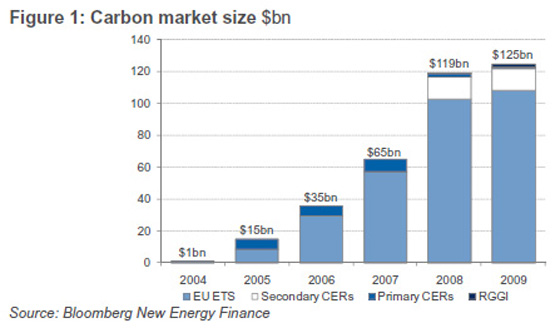

With proposed new schemes struggling to come to fruition, the main focus of carbon trading for the foreseeable future will be Europe’s ETS, which currently accounts for the bulk of global carbon trading (see chart).

Kicking in

Both Bloomberg New Energy Finance and Point Carbon have recently released figures showing that after a run of spectacular year-on-year growth, the global carbon market grew only marginally last year in value terms. According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, despite an increase in traded volume of 96% on 2008, the market gained just 5% in value, moving up from $119 billion in 2008 to $125 billion. That compares with an 83% rise the previous year.

Prices for European Emission Allowances (EUAs) in 2009 fell as low as €8.2/t at one point and the average price for the year was €14/t. That compares with an average of €24/t in 2008. Even this modest growth was supported by fraudulent VAT-related trading in the ETS, amounting to around 400 million tonnes (Mt) of transactions. As a consequence, 2010 could be the first year of negative growth for the carbon market, following government action to stamp out VAT-related fraud by making carbon transactions exempt.

Bloomberg New Energy Finance expects trading volumes to be lower in 2010, despite higher activity on the part of utilities as they cover their exposure under the auctions for the third phase of the ETS. Activity is expected to pick up again in 2011 ‘driven by the need for power companies to ensure further cover for themselves in the post-2012 [ETS] auctions, and increased activity in anticipation of new trading schemes in Australia and the US’.

Point Carbon expects ‘modest trade volume growth’ in 2010, amounting to a 5% rise on 2009. In terms of market value, the firm expects growth of 33% on 2009, largely because of firmer prices in the ETS. According to Tvinnereim: ‘We think that the price will go up by several euros from the middle of this year because phase three hedging will be starting. It will start kicking in in a couple of months.’

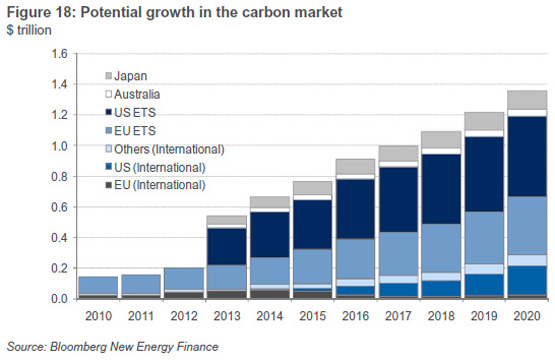

Looking further into the future, Turner’s view is that ‘the long-term prospects are sound’, as targets get tougher in Europe and other cap-and-trade schemes are implemented. Bloomberg New Energy Finance projects that the global carbon market could be turning over up to $1.4 trillion/year by 2020 (see chart).

Sikorksi of Barclays Capital expects that ‘It’s business as usual this year. And it’s wait-and-see on the markets outside Europe. We need some legislative clarity before we start to make big moves into those other markets. The legislative paralysis we’re seeing at the moment in places like Australia and the US is frustrating a lot of potential investment in emissions reductions. So those politicians have a fair amount to answer for.’

How the political debate will play out remains to be seen, but what is certain is that the ETS is enshrined in European legislation at least until 2020, and will continue to play a central role in European climate change policy. And the momentum behind other schemes, though it has faltered in the wake of Copenhagen, will pick up.

Discussion (0 comments)