Fraught with uncertainty

on

Fraught with uncertainty

Calculating the costs of generating electricity has never been as uncertain as today. This is the result of a number of factors, including the liberalisation of energy markets, the fast pace of technological development, the volatility of fuel prices and questions about climate policy.

|

| Nuclear energy is the most competitive option when financing costs are low |

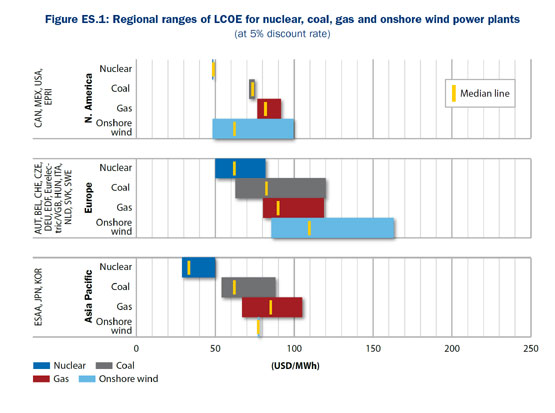

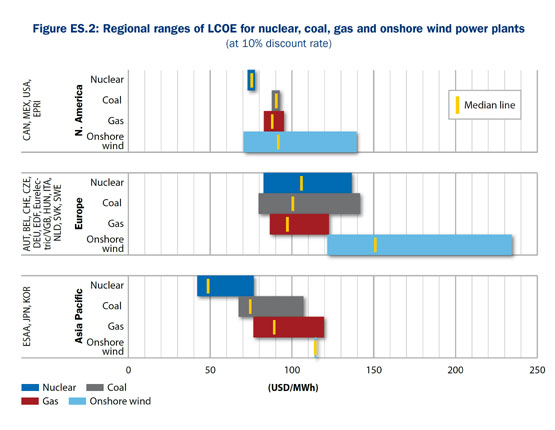

The IEA-NEA study notes that ‘no technology holds a consistent economic advantage at a global level under all circumstances’. Costs depend strongly on local conditions and on variable factors such as the cost of capital and the price of carbon. The researchers have nevertheless drawn some general conclusions. When financing costs are low (assuming an interest rate of 5%), nuclear energy, which requires high capital investment, is the most competitive option, followed by coal-fired power plants. With higher financing costs (10% interest rate), coal-fired electricity is the cheapest option. The costs of gas-fired power are highly dependent on gas prices and much less on financing costs. The attractiveness of onshore wind power depends very much on local circumstances. It is significantly cheaper in North America than in Europe. Offshore wind power is ‘currently not competitive’, the report notes. Neither is solar power.

|

|

| LCOE = levellised cost of electricity generation |

The accompanying graphs show the generating costs of nuclear, coal, gas-fired, and onshore wind power at a 5% and 10% discount rate. It should be noted that these results incorporate a carbon price of $30 per ton. They do not include transmission and distribution costs nor the additional costs of balancing and backup power that wind power requires. The study assumes a gas price of $10.30/MMBtu in Europe, which is roughly twice as high as current spot prices. The costs of nuclear power do include the costs for refurbishment, waste treatment and decommissioning after a 60-year lifetime.

Lack of experience

The report notes that the ‘precise cost competitiveness’ of the four technologies ‘depends more than anything on the local characteristics of each particular market and their associated cost of financing, as well as on CO2 and fossil fuel prices’. Each of the technologies has ‘potentially decisive strengths and weaknesses’.

About onshore wind the report says that ‘it is currently closing its still existing but diminishing competitiveness gap’. However, many European countries have ambitious plans to develop offshore wind. About this, the IEA says that ‘offshore wind is currently not competitive with conventional thermal or nuclear baseload generation’.

When we dig further into the data underlying the conclusions, some other points seem worthy of notice. All cost estimates are based on existing or commissioned power plants; they are not estimates of future costs. In this context, the researchers note that when it comes to nuclear power, there is a ‘lack of recent construction experience in many OECD countries’. This implies that the costs of newly to be built nuclear power stations could come out much higher – or much lower. Most recent experience comes from South Korea, where costs for nuclear power plants turn out to be relatively low.

For offshore wind, costs of actual or commissioned parks range from $101 per MWh (for a project in the US) to $260 per MWh (for a project in Belgium). The most valuable data in this sector could no doubt come from Denmark, which has the most experience building offshore wind parks. Unfortunately, as the report notes, Denmark did not supply any data.

Costs of solar PV vary from $225 to $600 per MWh. The two solar thermal plants included in the report have costs between $136 and $243 per MWh.

Uncertainties

Although the IEA-NEA report is indispensable as a benchmark study for the electricity sector, the authors note that producers and investors will always face large uncertainties when making specific investment decisions. In fact, as the authors note, since the publication of the report series started, in 1983, the market has never faced the ‘degree of uncertainty’ that it faces now. ‘In the medium term, investing in power markets will be fraught with uncertainty’, they write.

They give five reasons for this enormous uncertainty in the market. First, ‘the widespread privatisation of utilities and the liberalisation of power markets’ has reduced ‘access to data’.

Second, ‘policy factors’ have ‘rarely created more uncertainty for the cost of different power generation technologies than today’. Those ‘policy factors’ include carbon pricing, liberalisation and ‘re-regulation’ of markets, security of supply concerns for gas, the technical and regulatory uncertainties surrounding carbon capture and storage (CCS), feed-in tariffs ‘of limited duration’ for renewables, and regulatory uncertainty with regard to nuclear power.

Third, ‘after two decades of relative stability, the power sector abounds … with new technological developments’.

Fourth, relatively little new construction of power plants has taken place in OECD countries in recent years, making recent data harder to come by. Most newly built power plants have been combined-cycle gas turbines and onshore wind parks.

And the fifth source of uncertainty is ‘the rapid changes in all power plant costs’ in the last five years, e.g. as a result of ‘unprecedented inflation’ of construction costs and extreme volatility of fuel prices.

For governmental policymakers, the most important lesson of the study is that ‘choices exist’. The authors note that ‘governments play a key role when it comes to the costs of raising financial capital and the price of carbon’. Capital cost is a function of perceived risk – and ‘smart government action can do much to reduce risks’. Raising (or lowering) the carbon price would also make a huge difference – it would ‘decisively tilt the current competitive balance in one direction or another’.

For more information: www.iea.org or www.nea.fr

Discussion (0 comments)