IEA: the Age of Gas is coming, but will not solve all our energy problems

on

IEA: the Age of Gas is coming, but will not solve all our energy problems

China’s ambitious new gas development policy, troubles in the nuclear sector, the need to reduce carbon emissions and the discovery of vast new unconventional gas resources are all combining to lead us into a “golden age of natural gas”, says the International Energy Agency (IEA). But, the IEA adds, a global dash for gas will not change the industrial world’s dependency on oil imports and it will not reduce the need to take drastic climate measures. ‘There is no doubt that energy is going to be more expensive’, says IEA division head László Varró.

|

| Shale gas production in Pennsylvania, US |

No doubt some nice bottles of wine were uncorked in a number of gas companies’ board rooms last June when the IEA released its special report on the future of gas. The title of the report – “Are We Entering a Golden Age for Gas?” – was cast in the form of a question, but it seemed very much a rhetorical one. The answer provided by the IEA was a resounding Yes!

The Golden Age of Gas report is essentially an update of the IEA’s base case scenario (or “New Policies Scenario”) from its annual World Energy Outlook (WEO) report. The WEO is the IEA’s flagship publication, which each year sets out in great detail where the world’s energy markets are headed for in the next decades, under certainly policy assumptions. The Paris-based energy think tank of the OECD felt it necessary this year to come up with an intermediate “excerpt” from the WEO focusing specifically on natural gas. In this new report, the IEA concludes that the ‘outlook’ for natural gas is even ‘more positive’ than before.

There are several reasons why the IEA was prompted to proclaim the coming of a Golden Age for gas: first of all, the implementation by China of an ambitious new policy for gas use (in the new Five-Year Plan adopted in March 2011 by the National People’s Congress); secondly, a lower expected growth of nuclear power (in the wake of Fukushima), leading to a higher demand for gas; and thirdly, the increasing use of natural gas in road transport. These trends come on top of two major developments that are highly favourable to natural gas and that were already identified in the World Energy Outlook: the need to reduce carbon emissions and the discovery of vast new “unconventional” gas resources.

In its new Golden Age for Gas (GAS) Scenario, the IEA sees the share of natural gas in the global energy mix rise from 21% to 25% in 2035, compared to just 22% in the previous New Policies Scenario. Global demand will rise to 5.1 trillion cubic metres (tcm) in 2035 – 1.8 tcm more than today and nearly 0.6 tcm more than in the New Policies Scenario. China’s gas demand will rise from about the level of Germany in 2010 to match that of the entire EU in 2035. But China is not the only growth country. The IEA forecasts demand in the Middle East to double, reaching a level similar to China’s in 2035. Demand in India is expected to quadruple.

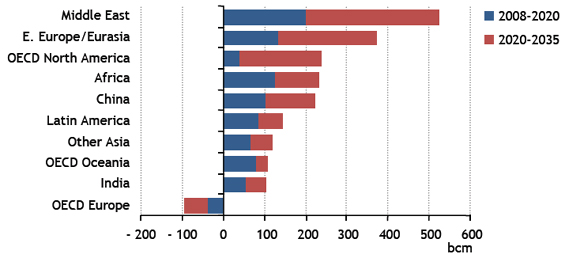

Obviously, such huge growth will require an equally large growth in production. Indeed, the increase in production necessary to meet the growth in gas demand up to 2035 will be equivalent to three times the current production of Russia! However, according to the IEA, ‘global natural gas resources can comfortably supply this demand’ – well beyond 2035, in fact. Thanks to the revolution in shale gas, tight gas and coalbed methane, all regions in the world have the potential to increase their gas production significantly ‘and enhance overall energy security’, notes the IEA, By 2035, unconventional gas will meet over 40% of demand and China will be one of the world’s largest gas producers. Europe is the only region in the world for which the gas outlook is less promising (see the box below). Better still, the production of this new gas will not cost much more than it does now and its environmental impacts are limited if well-managed.

All this sounds very upbeat of course, yet the report also contains some not so good news for gas advocates. First of all, oil will still be the world’s most important energy source in 2035, so the dash for gas is not going to take us into a radical new Energy Age, free of OPEC and Middle East concerns. Perhaps even more importantly – and surprisingly – in the Golden Age of Gas (GAS)-scenario global CO2 emissions will only be slightly lower than in the IEA’s New Policies Scenario. The Gas Age will, in fact, do little to diminish global warming, warns the IEA. This is because the increased use of natural gas will not only displace a lot of coal in power generation (thus lowering emissions), but also nuclear power (thus pushing up emissions). In addition, there is a risk that with cheap, abundant gas available, governments’ resolve to support renewable energy will waiver, which would be even worse news for the climate. Hence, natural gas advocates can hardly claim that a Golden Age of Gas will be a Golden Age of Climate as well.

Change in natural gas production by region in the GAS Scenario

European Energy Review’s editor Karel Beckman spoke to László Varró, Head of Division of the Gas, Coal and Power Markets Division of the IEA about some of the implications of the IEA’s Golden Age of Gas report.

EER: There has been a lot of talk in recent years about the unconventional gas revolution, but what may surprise some is that, as your report shows, even the world’s conventional gas reserves are huge.

Varró: Yes, conventional gas resources are indeed very large. In fact, in the past 30 years, the reserves replacement ratio has been consistently well over 100% globally. This means that despite the consumption of large amounts of gas, global gas reserves have been increasing continously for at least 30 years, maybe more! Even without the unconventional gas revolution, the picture of the resource base is very comfortable. And imagine that billions and billions of cubic metres of gas are still being flared in Russia, Nigeria, Iraq and elsewhere. The amount of gas flared in oil production is roughly equal to the gas consumption of a large European country. So the resource base is very large.

EER: What will be the impact of the unconventional gas development?

Varró: The unconventional gas revolution has roughly doubled the gas resource base. Not only that, unconventional gas has a different and wider distribution than conventional resources. At this moment, Russia, Iran and Qatar control half the world’s conventional resources. This is a bigger concentration than in oil. Clearly there are geopolitical issues with Iran. Qatar, although a stable country, is located in the Gulf, which has a bit of history. And there have been issues with Russian gas as well. With shale gas, however, we have very large resources in countries with massive domestic energy demand, such as the US and in China. If there is one country that is brightening the future of gas, it’s China. Today, gas is not playing a major role in the Chinese energy mix, but that is going to change rapidly. If you want to be big in gas, you will need to be big in China.

EER: Can we say the same about global oil resources?

Varró: There are large oil resources as well, but the resource availability is much better for gas. No doubt about that. And we do have unconventional oil, like tar sands and shale oil, but not on the scale of unconventional gas.

EER: To what extent does the Golden Age of Gas report reflect new insights within the IEA?

We did not come to this realisation in the last few months or so. It has been a gradual process over the last couple of years. But the speed of the shale gas revolution took us by surprise, as it did everyone. Remarkably, on the same day in June 2005 on which the CEO of ExxonMobil declared that US gas production had entered an irreversible decline, shale gas production started in the Barnett basin.

EER: There is still a lot of scepticism about the possibilities of shale gas and other types of unconventional gas. Some critics argue that the decline rates in the North American shale gas plays are very high, so the resources might well be overestimated.

Varró: We don’t agree. In our estimate the major US shale gas plays are comparable in terms of recoverable resources to the supergiant conventional fields. Decline rates are indeed high which leads to intensive drilling, but there have been genuine technological developments in costs and operations. We have very little doubt that the further growth of US production of shale gas is sustainable. And also the resource base outside the US is very large. Having said that, replicating the US success elsewhere is easier said than done. The US has a very favourable combination of good geologic conditions, highly developed gas markets, good infrastructure, an adequate regulatory framework, and a well-developed oil and gas services industry that can ramp up its activities at short notice. That combination of geological, policy and corporate factors is not easy to replicate. Nevertheless, we do expect commercial shale gas production to take off outside the US.

EER: What about the environmental objections to shale gas production. Some critics have argued that shale gas production will lead to much higher CO2 emissions because of the release of large amounts of methane. Others are afraid that hydraulic fracturing can lead to pollution of underground water reservoirs.

Varró: Natural gas is predominantly methane which has a high greenhouse gas potential. If you let it out in the air, that’s bad news. Our assessment suggests that if shale gas production is properly managed, methane emissions are something you can deal with technically. Then lifecycle emissions of shale gas are only marginally higher than for conventional natural gas, about 3%, and well below those of coal. Of course, if you manage it badly, that’s different. About water pollution – I saw the Gas Land movie of course. Hydro-fracturing is a complex technology, so you need a proper regulatory framework, you need environmental safeguards and you need good management. But if you ask is the technology inherently unsafe? No.

We see absolutely no reason that it could not be done without polluting the environment if it is properly done.

EER: Will the Golden Age of Gas usher in a world where we will not be so much dependent on oil imports and OPEC anymore?

Varró: In the Golden Age of Gas Scenario there is some substitution from oil to gas. First of all, certain countries like Italy, Japan, and certain emerging economies still use oil in power generation. This will be replaced by gas. Secondly, gas is beginning to make inroads as a transportation fuel. The bigger the price differential between oil and gas, the greater the incentive to use more natural gas-based vehicles. But these effects are not very large. Even in the Golden Age of Gas Scenario oil remains the largest energy source in 2035. There will still be a very large international oil trade, and very large import dependency by major industrialised countries. So oil supply security will not go out of fashion.

EER: So this is not doing anything to reduce the IEA’s concerns about the oil market.

Varró: No. We continued to be concerned about the oil market. Prices remain high despite the economic conditions. We are still in the danger zone. The tax consumers pay as a result of the high oil prices is comparable in size to the economic stimulus.

EER: But is the oil price still about supply and demand?

Varró: Yes, we do not believe that financial speculation has a significant effect on the oil price. At the end of the day it is supply and demand that counts. That’s why we have these friendly conversations with OPEC. We have some OPEC supply coming to the market, but not enough. We clearly see the possibility of a tight market going forward.

EER: OECD Europe is the only region in the world that sees its gas production decline in your scenario. What do you think of the recent Norwegian gas discoveries? Aren’t they exciting?

Varró: We are happy with all additional supplies. In that sense the Norwegian discoveries are good news, but they don’t change the big picture, which is that European import dependency is increasing in the gas market. We don’t see these discoveries reverse the decline of domestic production in Europe.

EER: One message stressed by the IEA recently is that ‘the era of cheap energy’ is over. Does a Golden Age of Gas make any difference in this respect.

Varró: No, that’s not how we look at it. If you go back 200 years in time, China’s GDP was roughly comparable to that of Europe. Then the Industrial Revolution started, and roughly 10% of the global population took off. The symbol of the Industrial Revolution was of course the steam engine. It was the story of fossil fuels. This led to a situation where a couple of decades ago 10% of the population was consuming more than half of the world’s resouces. This was not sustainable. Now the rest of the world is catching up. Their energy consumption is converging with ours. This will put a huge pressure on energy demand for a long time to come. And there is the pressure of decarbonisation as well. We use more energy, but we have to produce less CO2. Add this up and there is no doubt that energy is going to be more expensive.

EER: Are you worried that the message is not getting through to politicians?

Varró: Yes. Yes. Politicians have to explain that energy costs will need to rise. Take decarbonisation. If you are a citizen of an average advanced democracy, you emit roughly 10 tons of CO2. A sustainable level would be about 1 or 2 tons. So you are 8 tons over your sustainable carbon budget. We can achieve quite significant decarbonisation at a price of $100 per ton CO2, which for an average citizen would be $800 per year, or just $70 per month. This is basically the price of a couple of beers on a Friday night. So if you ask, can we spare this money, yes, we can. But still, we don’t have the framework to make it happen.

|

Europe's gas future If the world is entering a Golden Age of Gas, the question is, can the same be said for Europe? Not quite. In fact, in the IEA’s Golden Age of Gas Scenario, Europe (“OECD Europe”) is the only region in the world that will see a production decline in the period to 2035. The new scenario does take into account additional production from new Norwegian discoveries, but this will not change the overall picture. Gas output in OECD Europe fell by 6% or 20 billion m3 (bcm) between 2005 and 2010, in spite of an increase of 20 bcm of Norwegian production. This trend is expected to stay the same in the coming decades. Russia on the other hand, already the largest gas producing country with the US, will see strong growth in gas production. As demand in Europe is expected to grow steadily (even more in the new scenario than in the old one), it follows that Europe’s gas import dependency will continue to grow. Europe’s import was 50% of consumption in 2010, and this is expected to rise to 70% in 2035. This is not a new insight, but it is clear that the Golden Age of Gas will not change the European gas picture in any way for the foreseeable future. On a positive note, the IEA expects European imports to become more diversified, with a growing share of LNG. The IEA also notes that even OECD Europe, despite its unfavourable gas situation, has significant domestic gas resources. It estimates OECD Europe’s recoverable resources of conventional gas at 22 trillion cubic metres (tcm) and its shale gas resources at 16 tcm. This is equivalent to roughly 70 years of current consumption (about 550 bcm per year). The full World Energy Outlook 2011, which will be published in November, will cover natural gas issues in great detail, including the impact of lower nuclear investment on gas and other energy sector. In addition, the WEO 2011 will have a special country focus on Russia, the world’s biggest gas producer. If the world is entering a Golden Age of Gas, the question is, can the same be said for Europe? Not quite. In fact, in the IEA’s Golden Age of Gas Scenario, Europe (“OECD Europe”) is the only region in the world that will see a production decline in the period to 2035. The new scenario does take into account additional production from new Norwegian discoveries, but this will not change the overall picture. Gas output in OECD Europe fell by 6% or 20 billion m3 (bcm) between 2005 and 2010, in spite of an increase of 20 bcm of Norwegian production. This trend is expected to stay the same in the coming decades. Russia on the other hand, already the largest gas producing country with the US, will see strong growth in gas production. As demand in Europe is expected to grow steadily (even more in the new scenario than in the old one), it follows that Europe’s gas import dependency will continue to grow. Europe’s import was 50% of consumption in 2010, and this is expected to rise to 70% in 2035. This is not a new insight, but it is clear that the Golden Age of Gas will not change the European gas picture in any way for the foreseeable future. On a positive note, the IEA expects European imports to become more diversified, with a growing share of LNG. The IEA also notes that even OECD Europe, despite its unfavourable gas situation, has significant domestic gas resources. It estimates OECD Europe’s recoverable resources of conventional gas at 22 trillion cubic metres (tcm) and its shale gas resources at 16 tcm. This is equivalent to roughly 70 years of current consumption (about 550 bcm per year). The full World Energy Outlook 2011, which will be published in November, will cover natural gas issues in great detail, including the impact of lower nuclear investment on gas and other energy sector. In addition, the WEO 2011 will have a special country focus on Russia, the world’s biggest gas producer. |

|

Who is László Varró? László Varró joined the IEA in 2011 as the Head of Gas Coal and Power division. The division undertakes the analysis of gas, coal and electricity markets and policy developments with a special focus on supply-demand balance, capacity investments, supply security issues as well as the implications of climate policy for the gas and electricity systems. Before joining the IEA, Varró worked in the private sector as the Director for Strategy Development at MOL Group, a publicly quoted integrated energy company. There he was responsible for demand and price forecasting, investment capital allocation and the incorporation of energy policy developments into corporate strategy. Before MOL Group, he was the Head of Economics and Price Regulation at the Hungarian Energy Office, the national gas and electricity regulator in Hungary. Varró is an economist by training with graduate degrees from the Corvinus University in Budapest and the University of Cambridge. |

|

Marcellus controversy Note that the United States Geological Survey (USGS) has just presented a new assessment of the shale gas resources in the Marcellus basin. According to the USGS, Marcellus contains a lot more gas than previously estimated. However, this amount turns out to be a lot less than figures used by the US Energy Information Administration (EIA). Hence, the EIA has now been forced to cut its estimate of US gas reserves considerably. See here for the relevant links. |

Discussion (0 comments)