Is Europe giving up on energy efficiency?

on

Is Europe giving up on energy efficiency?

Virtually everybody agrees that energy efficiency is the number one energy priority for Europe, that it can provide growth, jobs, energy security and environmental benefits, and that it needs intervention by policymakers to really get going. So why is it so difficult for Brussels to agree on a legislative framework to drive energy efficiency? The EU's 27 member states and the European Parliament are further apart than ever in negotiations on a new EU energy efficiency law. The major measure on which a deal is likely to centre is a requirement for energy retailers to deliver 1.5% energy savings per year from their customers. Sonja van Renssen reports from Brussels.

|

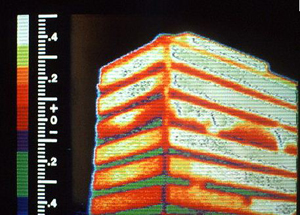

| Thermal picture showing the energy loss of a building (c) Less-en.org |

Energy efficiency is testing the Europeanization of energy policy in the EU and indeed broader European policies such as austerity measures. Member states, the European Commission and the European Parliament are negotiating a new EU energy efficiency directive tabled by the European Commission last summer, but so far with little result. The Commission and Parliament are asking member states to endorse and implement efficiency measures that will cost them time and money in the short-term for long-term gain, but the EU-27 are unwilling to go along.

This while Europe is on track to deliver only about half of a 20% saving in primary energy consumption by 2020 promised by European leaders in 2007. This 20% is equivalent to a saving of 368 million tonnes of oil equivalent (mtoe) or to limiting primary consumption in 2020 to 1474 mtoe. The final form of the EU energy efficiency directive currently under negotiation will to a large extent determine the fate of this promise - and the economic growth, job creation, energy security and environmental benefits that go with it.

It's a strange situation, as virtually everyone is convinced of the importance of energy efficiency. As Bill Colton, Vice President for Corporate Strategic Planning at ExxonMobil put it at a seminar in Brussels on 8 May: "The greatest source of energy in the future will be learning how to use it more efficiently." The Council of EU Ministers, which represents member states in Brussels, has been talking about how important energy efficiency is since March 2007. But these same governments cannot agree on EU policies to drive it forward.

Binding measures not targets

Last summer the European Commission put forward an ambitious if complicated proposal for a new energy efficiency law that is intended to ensure that the EU meets its non-binding 20% energy efficiency target for 2020. Of all the EU's climate and energy targets, the one for energy efficiency is the only one that remains non-binding - and the only one on which the EU is woefully behind. As a simple remedy, many have argued for making this target binding, like the EU's CO2 reduction and renewable energy targets. But member states have stubbornly resisted all efforts in this direction.

The proposal from the Commission last summer avoided binding targets, but instead consisted of a long list of binding measures, including energy saving obligations for energy retailers, building renovation requirements, public procurement measures, a legislative push for combined heat and power (CHP), smart metering and smart billing requirements, mandatory energy audits and more efficient transmission networks.

But if member states did not want binding targets, it appears these binding measures are equally difficult to swallow. At one point it looked as if the binding targets would resurface as a tantalizingly simple alternative to the very long - and often confusing - list of measures now on the table. The idea was that the 20% target would be shared out amongst member states and national governments would

| The idea was that the 20% target would be shared out amongst member states and national governments would be free to meet their targets as they saw fit |

The European Parliament, which has full co-legislative power to decide on the Commission's proposal for a new EU energy efficiency directive, has re-introduced a call for binding targets in its own position on the proposal, adopted on 28 February (see 1 March blog entry). But in the face of fierce opposition from the Council, this is a bargaining chip they will very likely have to give up. The question is for what.

Hesitation

Why have member states remained so reluctant to embrace EU action on energy efficiency? In a policy paper prepared for an informal meeting of EU energy ministers in Horsens, Denmark at the end of April, the Commission again laid out the positive impact of its proposal: a €34bn increase in EU GDP and 400,000 net new jobs in 2020. A second, energy sector-specific assessment suggests an annual average reduction in energy-related expenditure of about €20bn from 2011-20. The €24bn a year investment needed in energy efficiency will be more than recouped by €38bn saved on fuel and €6bn saved on electricity generation and distribution costs.

Still, member states are not convinced, for three main reasons. Number one is the economic crisis. In the prevailing climate of austerity in Europe, finance ministers today are much more concerned with limiting expenditure than planning investment. It does not matter if the Commission has made a convincing business case, the public purse is empty and governments must save, not spend. This is a problem for energy efficiency, which delivers long-term savings but requires substantial upfront investment, for example when it comes to installing heat pumps or renovating buildings.

What could change this is a growing feeling in Europe that austerity alone will not lift the economy out of recession. New French president Francois Hollande has vowed to revisit the pact on EU budget

| It does not matter if the Commission has made a convincing business case, the public purse is empty and governments must save, not spend |

A second reason member states are reluctant to embrace the energy efficiency proposal is a feeling that it shouldn't be the EU deciding on detailed measures in this field. There is no common European energy policy the way there is a common European environmental policy, one EU source says. There are still 27 member states with 27 energy systems and 'national systems are just not ready to accept ideas [from Brussels] and uniformly implement them'.

Member states are also wary of the additional administrative burden associated with many energy efficiency measures - the Commission's proposal to renovate 3% of public building floor space annually, for example, requires an inventory of public buildings, their size, their current state, their potential for improvement and the cost involved.

Other member states already have their own efficiency initiatives in place - energy saving obligations for energy retailers in France and the UK for example - and fear pan-European legislation could interfere with their own efforts. Such EU meddling could be avoided of course if there was an agreement on national energy saving targets, with member states free to fill them in as they see fit, but as we said this is a no-go area for the Council.

The third main reason why member states are reluctant to embrace the Commission's energy efficiency proposal has to do with the EU Emission Trading Scheme (ETS). Many fear that doing more on energy efficiency would run counter to CO2 emission reduction efforts though this scheme. They argue that more efficiency means fewer emissions and an even lower carbon price than the paltry €7 a tonne today. This fear of a clash between energy efficiency and mitigation policy has led to the strange situation whereby some of Europe's leading climate action advocates, such as the Netherlands, are wary of the efficiency proposal, while some of climate action's traditional opponents, such as Poland and Italy, are its biggest supporters.

|

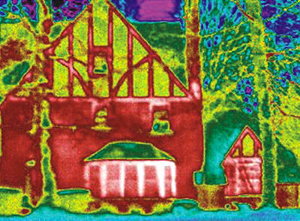

| Heating up the outside... (c) Eco-Vision Sustainable Learning Center |

A politically powerful call for an ETS fix in the energy efficiency directive, is unlikely to survive the negotiations, EU sources say.

EU-27 cannot agree

With all their concerns, members states have struggled to agree a common position to bring to the negotiating table with the Parliament. There have been three meetings between the Council, Parliament and Commission, the last on 8 May. It was only at this last meeting that some tentative progress was made on some of the smaller, less controversial elements of the proposal, such as supply-side efficiency, according to EU sources. But member states still do not have a common position on the major issues and negotiations with the Parliament have yet to really get going on these. Three more formal negotiating sessions are planned - on 29 May, 5 June and 13 June - with a view to sealing a deal by the end of June when Denmark hands the rotating EU presidency over to Cyprus.

A Commission analysis of the Council's position concludes that member states have diluted the original proposal to such an extent that it would deliver only 58 mtoe of energy savings in 2020, or 40% of the savings envisaged by the Commission. The Commission's original proposal added up to some 150 mtoe of savings in 2020, or about three-quarters of the 200 mtoe gap (to the 368 mtoe saving target). The last quarter would be delivered by separate efficiency initiatives in transport. The Parliament tightened up the proposal further so that it alone would bridge the entire 200 mtoe gap. EU member states say the new law should not aim to close the gap to the 20% energy efficiency target in 2020 however, but rather make a 'significant contribution' to doing so. To some, this appears to call into question member states' very commitment to the target.

It also leaves the EU-27 very far removed from the Parliament's position. For the draft energy efficiency directive to become law, the two institutions will have to meet somewhere in the middle. There are no

| A Commission analysis of the Council's position concludes that member states have diluted the original proposal |

A possible deal

But the Danish EU presidency has insisted and continues to insist that a deal by June is doable and a priority. Of all the measures on the table, the one around which a deal looks most likely to be struck is the Commission's proposal for member states to require energy retailers to deliver a 1.5% energy saving among end-users every year, based on sales volume in the preceding year. This is recognised as the "engine" of the proposal by all three institutions - the Commission, Council and Parliament - because it would deliver more than half the planned savings of the new law under any scenario.

Overall, the Parliament has strengthened the potential impact of the proposed saving obligation by increasing its scope in the sense that savings could also be delivered in the transport sector. Member states, conversely, have introduced a long list of dilutions. They would prefer a gradual phasing in of the 1.5%. They also argue that supply-side savings (from generation, transmission and distribution) and past actions on energy efficiency should be included in the 1.5%. In addition, they want to exclude up to 40% of the energy consumed by industries covered by the Emission Trading Scheme. This would dramatically reduce the total primary energy consumption covered by the savings obligation.

The Commission has calculated that the Council's proposals would slash the contribution of its proposed energy saving obligations from 75 mtoe to just 30 mtoe in 2020. Since the informal EU energy ministers meeting in Horsens, Denmark, however, some ministers have reportedly conceded that the watering down is getting a bit preposterous and most recently there is talk of a list of flexibility options that governments would have to pick from, e.g. they could include transport and exclude part of the ETS or vice versa. Another option under discussion is bundling together several options with a cap of say 20% on the flexibility this could introduce for the 1.5% annual saving.

Bubbling away

The other two most controversial issues under discussion are building renovation and public procurement requirements as well as the regulatory push for combined heat and power (CHP). MEPs want "deep" renovations and a building renovation roadmap that would force member states to cut the

| The other two most controversial issues under discussion are building renovation and public procurement requirements as well as the regulatory push for combined heat and power |

On CHP, member states find the Commission's proposal, which effectively requires all new combustion installations with capacities of 20W or more to be CHP units, too restrictive. They only want to impose a requirement for a cost-benefit analysis of CHP when installations are built, with no obligation to act on its results. MEPs want all new installations to be CHP unless a cost-benefit analysis shows this is not economically viable.

Other issues are bubbling away in the background. One is smart metering and billing requirements. Smart meter supplier Landis+Gyr says the current Council version of the draft energy efficiency law 'will not be enough to ensure that the smart metering roll out can make an effective contribution to energy efficiency'. The Smart Energy Demand Coalition (SEDC) has accused the Council of ignoring amendments from the Parliament that would enable the introduction of large-scale demand response mechanisms. These would allow industrial end-users to sell energy savings back into the wholesale market to cut overall energy consumption. SEDC Executive Director Jessica Stromback says companies are missing out on €3.5-5bn in revenues and 20% energy savings.

Getting it done

The upshot of it all is that member states are currently moulding the new EU energy efficiency directive to deliver a measly 58 mtoe of energy savings. Yet they insist they remain committed to the 20% energy efficiency target for 2020, which, as we have seen, equates to a 368 mtoe saving, with 200 mtoe of this still to be delivered through new policies. So how will this gap be covered?

Sources in Brussels say member states believe the transport sector can deliver more than the 50 mtoe saving assigned to it by the Commission. They also cite eco-design standards for boilers, which have been under discussion for years now but are yet to be finalised. The Commission is reportedly understaffed on this front and the issue is politically sensitive since the savings could indeed be quite enormous – 50 mtoe one expert estimates.

But in both cases the logic is not so easy to follow. Transport has proven one of the most challenging sectors for climate and energy policymakers to tackle and the installation of more efficient boilers would presumably be covered by the 1.5% energy saving goal for end-users set out in the energy efficiency directive.

Some observers put a positive spin on the current deadlock. They say the new energy efficiency law should not be judged only on what it delivers for the 2020 target, but also for the longer term, in terms of behavioural and cultural change towards energy efficiency. That may be so, but the current economic crisis provides an immediate impetus to act on energy efficiency.

The root of the problem is probably that many policymakers see a direct link between energy

| The root of the problem is probably that many policymakers see a direct link between energy consumption and economic growth and prosperity |

But for energy efficiency to really take off it probably must become part of the new European growth and employment agenda, EU sources say. In the words of the Parliament's lead negotiator Claude Turmes: 'Investing in energy efficiency is the best way of investing in Europe.'

Discussion (0 comments)