The lights are back on in Albania

on

The lights are back on in Albania

After years of major power shortages, the Albanian energy sector is finally getting back on its feet, thanks to new government policies and privatisations. Environmental groups, however, are critical of the lack of transparency surrounding all the new investments.

|

| Worker repairs power pylon in Tirana, Albania |

| Article Highlights: |

| - Until recently Albania suffered from regular power shortages and the World Bank warned that the country’s power crisis might prove to be disastrous for the country’s economic development. - However, the situation has improved a lot recently. No major new power failures have occurred since 2008 and investment plans for new power production and distribution abound. - The improvement is due to the government’s decision to break up the monopoly of the inefficient national operator KESH and to encourage foreign investments. - On the downside, environmental activists are worried that foreign companies are being allowed to spoil Albania’s natural environment. |

The reasons for the sorry state of the Albanian electricity sector were not hard to find. Although in the 1990’s the formerly isolated communist country had turned into a – rather chaotic – democracy with an open market, the energy sector remained in the hands of state-owned utitlity KESH, a bureaucratic monster plagued by lack of money, poor management and corruption.

For nearly twenty years, KESH did nothing but focus on crisis management, while electricity demand steadily increased, says energy specialist Gjergj Simaku, who is attached to the University of Tirana. ‘No new production capacity was created and only part of the national plan for the energy sector, drawn up in 2003, was implemented.’

Recently, however, things appear to have changed. No major power failures have occurred since 2008. Suddenly plans are on the table for new wind parks, hydro-electric and thermal power stations and even nuclear energy plants. The construction of a 100 MW power station in the southern seaport town of Vlore, partially financed by the World Bank and EBRD, is almost completed. And last year, part of KESH was finally privatised. What had seemed impossible for years suddenly happened.

Theft

‘I do not expect any more power failures’, Fatjon Tugu, head of the energy department of Albania’s Ministry of Economic Affairs, says confidently. He is convinced that the reforms implemented these past few years have finally brought stability to the long-ailing sector.

It was the EU and international organisations like the World Bank and EBRD (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) which pressured the Albanian government into implementing reforms such as the liberalisation of the energy sector, raising electricity tariffs and privatisations.

Perhaps the most important measure was the privatisation of KESH’s distribution company, Operator i Sistemit in Shpemdajes (OSSH). OSSH suffered from a range of problems: high losses, theft, a failure to collect payments. Many households only had a meter fitted last year. Some 40% of the population did not pay for their electricity at all. As a result, the company did not have enough money to invest in the maintenance and construction of new electricity production or transmission. KESH had to import electricity, for which it needed to borrow money from the government and banks. Due to a lack of interconnections, a dominant position of energy traders and a regional energy shortage, import prices were high, further burdening KESH’s budget, causing a loss of over €200 million in 2007.

In September 2008, Czech company CEZ took over 76% of OSSH for €102 million. Transmission and distribution are now no longer the responsibility of the state. The Czechs have promised to invest €200 million in the distribution network over the next five years and to assume OSSH’s debts of €122 million.

CEZ is using this take-over to strengthen its position in the West Balkans. The company is confident that its experience gained from taking over distribution companies in the Czech Republic, Bulgaria and Romania will help it succeed in Albania. The Czechs view Albania as a growth market: consumption of the nearly one million Albanian customers is expected to rise by 5% annually, making it the second fastest growing market in Europe after Turkey.

The takeover agreement stipulates that the Czechs must reduce the percentage of lost or pilfered energy by 50% within five years or else bear the costs themselves. In return, CEZ is permitted to increase tariffs by 8% to 15% by 2010. It may introduce three rate increases in five years. According to Tugu, it was agreed that this year, ‘in connection with the elections, CEZ is not allowed to increase the consumer price for electricity’, which currently is 7 eurocents per kWh.

Albania, as all Balkan states, has always had low consumer electricity rates. Fearing social unrest and loss of votes, no Albanian government has dared to risk changing this practice, even though a price increase was badly needed to pay for improvements in the sector. The consumption price is still 50% less than the average rate consumers in Western Europe pay.

Foreign investors

In the production sector changes are also underway. Foreign investors are building new production capacity – for the first time since the 1980s. ‘Investors are interested in Albania because we have the resources to generate energy: mountains, rivers and suitable locations for their power stations’, says Tugu. The government has passed laws to facilitate private-public partnerships and loans for sustainable energy.

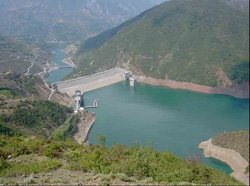

An example is Austrian energy company Verbund, which is building the first new hydro-electric power station in Albania in 30 years, together with its Austrian partner EVN. Verbund and EVN have signed a 30-year contract with KESH to build the 48 MW Ashta power station on the river Dina, requiring an

| Transmission and distribution are now no longer the responsibility of the state. |

Some people wonder whether this investment in expensive green energy is economically efficient for an impoverished country like Albania. KESH will pay €80 per MWh on average for the electricity it will buy from the Verbund. Tugu believes that the costs can be recovered by the income from electricity exports. ‘Our plan is to obtain maximum benefits from the hydro-electric power stations in the coming years. Once we produce sufficient electricity, we can export during peak hours.’ Albania has plans to build new transmission lines to Greece, Kosovo and Montenegro.

Watch list

In addition to the Verbund venture, there are other initiatives. A consortium including EVN and Norwegian Statkraft, has started the construction of three hydro-electric power stations with a total capacity of 320 MW. The project is expected to take 8 years and estimated to cost €1 bn.

The Albanian government is also planning two large projects, both in seaports: a 100 MW oil-fired power station in Vlore (to be completed in 2010) and an 800 MW coal-fired power station in Durres. Oil and coal must be imported for both power stations. Prime Minister Sali Berisha has said the north of the country is an excellent location for the construction of a nuclear power station.

|

|

The Fierza hydro power station in Albania |

But Simaku says it is justified to view the investment climate in Albania critically. He says the government is not too particular when it comes to upholding the law and foreign companies are given a clear field to abuse Albania’s natural resources. ‘I am all for diversifying energy production but decisions are being made that are neither backed by any feasibility study nor by any laws protecting the environment or the local population. These decisions go against expert advice.’

Environmental specialist Xhemal Mato of Eco-movement in Tirana is critical of the two seaport projects. Both towns are densely populated and are tourist attractions with attractive beaches and surrounded by nature preserves. The government is not being truthful about the consequences of waste and emissions, says Mato. Referring to the project in Durres, to be built by Italian company Enel, he says: ‘An independent and internationally financed environmental study has enabled us to prove that the government has lied about costs and the CO2 emissions. These are much higher than the authorities maintain.’ The project has been stopped for the moment, partly as a result of the study.

Near Vlore, in the protected Karaburun park, the government has given permission to Enpower Albania, a subsidiary of the Italian Moncada Energy Group, to build a 500 MW wind park. Critics say it is not clear how this project was approved. The wind park will mainly produce electricity for Italy. Planned new transmission lines under the Adriatic Sea are to link the Albanese and Italian networks. Critics are afraid that both nature and tourism will suffer from this project.

‘Investors are allowed to do as they please because we need the money’, says Matto, who is pleading for stricter controls. ‘This just proves once again that we have not reached the EU level.’

And there may be other problems on the horizon for the Albanian electricity consumer. ‘Last year’s rain and elections guaranteed our electricity supply’, says Simaku. ‘Now the money has run out and we may have to wait for new production capacity to come onstream.’

To read Anke Truijen’s earlier report in European Energy Review of November 2007 on the then-raging Albanian power crisis, click here.

Discussion (0 comments)