Time to reform the EU Emission Trading Scheme

on

Time to reform the EU Emission Trading Scheme

While the ongoing debt crisis has absorbed European attention, another centrepiece of European economic integration is also seeing hard times: the European Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS). According to Thomas Spencer and Emmanuel Guérin of the French think tank IDDRI (Institut du Déeveloppement durable et des relations internationales), the ETS needs to be urgently reformed if it is to play its role as backbone of European climate change policy. Failure to do so will lead to huge extra costs and damage the credibility of the EU. They analyse the key weaknesses of the ETS and suggest three steps that could be taken to salvage the system.

|

| The EU's Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) is not performing well and needs to be urgently reformed |

The ETS is a centrepiece of European climate change and energy policy, as recently reaffirmed by the Commission's 2050 Energy Roadmap. Its objective is to contribute to reducing emissions to levels considered "scientifically necessary" in a "a cost-effective and economically efficient" manner (article 1). The Energy Roadmap and the Climate Roadmap released in March 2011 have placed this objective within a long-term context: by 2050, the EU economy will need to be almost fully decarbonized.

Long-term credibility

The objective of climate policy should be to create a credible, "investment grade" framework to guide private economic decisions. A short-term carbon price can make some energy efficiency measures profitable, and potentially some cheaper renewable energies (onshore wind and biomass). But for more expensive, long-term projects what matters are firms' expectations about future carbon scarcity. These will be based on the long-term credibility of the targets, institutions, and policies in place. The ETS thus may be said to have two objectives: firstly, to make short-term emissions reductions profitable; and secondly, to contribute to credible long-term expectations of future carbon scarcity.

Econometric analysis (see here and here) and stakeholder interviews (see here) indicate that the ETS is performing to a certain degree against the first criterion, in leveraging some energy efficiency and fuel switching. However, analysis suggests that the overall role of the ETS in emissions reductions is relatively marginal, with other policies (such as renewable and energy efficiency targets) currently playing a more significant role. With the current low price, the ETS is probably not making a fully cost effective contribution to emissions reductions, meaning that greater effort is required from other, more expensive policies (see here). A policy mix is always necessary, as the carbon price alone will not induce energy efficiency measures nor higher cost, low-carbon technologies, but the current low carbon price leads to a misbalance within the policy mix, raising the costs of climate policy.

At the same time, the ETS is having an insufficient impact on long-term investment and innovation in the sectors it covers (see here and here). The short-term price signal is too low, and too volatile, to send credible signals about policymakers’ commitment. More importantly, in the long-term there is debilitating uncertainty about future carbon scarcity.

The ETS directive does contain an indefinitely declining cap (1.74% per year), but this is not perceived as credible, or sufficient, by market participants, because it is not consistent with the EU’s long-term

| The end result is a weak, and volatile, short-term price signal to 2020, and paralyzing uncertainty thereafter |

The end result is a weak, and volatile, short-term price signal to 2020, and paralyzing uncertainty thereafter. These two deficiencies reinforce each other. A credible long-term framework could help to support short-term carbon prices; and short-term carbon prices give credibility and visibility to long-term objectives. In sum, neither the short- nor the long-term policy framework really give useful information to guide large-scale investment.

What is at stake?

Failure of the ETS would have far-reaching consequences for the European energy sector and the EU as a whole. Four important things are at stake. Firstly, businesses must make significant investment choices in the near future, as the EU energy sector is approaching a large investment cycle. The IEA estimates that the EU power sector will need $694 billion investment in the current decade, and $1080 billion in the period 2021-2035. As argued by the Commission, “[t]he pattern of energy production and use in 2050 is already being set”. Thus it is vital to ensure that the current policy framework can shape the investment decisions that will define the EU energy sector over the next 30-40 years. Otherwise, the policy framework risks distorting and delaying investment, and raising policy costs.

Secondly, as well as coordinating private actors, the ETS is a crucial tool in guiding Member State energy and climate policies. The current weakness and damaged credibility of the EU ETS risks the “renationalization” of climate policy, as indeed presaged by the UK implementation of a carbon floor price to make up for the low ETS price. A number of EU Member States (e.g. UK, Germany, and Denmark) have adopted ambitious long-term policies, to which the low ETS price is proving more hindrance than help. Fragmented and uncoordinated climate policy in the EU will be more expensive, less effective, and, in the long run, probably less ambitious.

Thirdly, Europe’s international leverage in climate policy is determined by its cohesiveness. Durban demonstrated that a coherent and strategic EU position, based on a clear proposal, can move other

| The current weakness and damaged credibility of the EU ETS risks the "renationalization" of climate policy |

Finally, the EU ETS will be an important source of government revenue in the period 2013-2020. Using the prices assumed by the Commission in its latest modeling (€17-25 by 2020), the ETS would generate €150-190 billion over 2013-2020; under a 2020 price consistent with the Commission’s pre-crisis modeling (€30-55) it would generate €200-310 billion, according to research by Climate Strategies. Under current price forecasts, this means foregone revenues in the order of €50-210 billion. In the context of the fiscal and employment crisis, fiscal reform of energy and labour taxation could be an attractive part of the solution. This revenue could also be important for supporting research and development of low-carbon technologies in key sectors (power, steel, cement etc).

Thus, the long-term effectiveness, internal coherence, and international leverage of EU climate policy are potentially at risk if the ETS continues to underperform.

Fixing the EU ETS: a three-step process

The weakness of the ETS lies in three essential elements. Firstly, there is the current weak and volatile price signal, arising from the current oversupply of permits. Secondly and more importantly, there is the lack of a clear and credible post 2020 framework. Thirdly, there is the lack of institutional processes and mechanisms to ensure the credible future management of adjustments to the ETS. Therefore reform to the ETS must take into account these three aspects. The timing of the individual measures would be important, as explained below.

The most discussed short-term reform option is that of a “set aside”. Under this option, a quantity of emission allowances would be withheld from auctioning during Phase III, 2013-2020. The attraction of this option is essentially political, not economic. It can be undertaken by a decision of the Commission under its competence to define the amount and timing of allowance auctions. Therefore it would not entail reopening the emissions trading directive, which would be difficult in the current political climate.

|

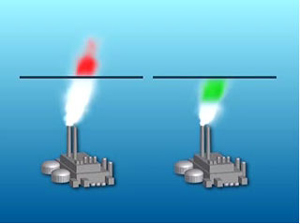

| Capping carbon (illustration: European Environment Agency) |

The second avenue is to send precise and credible signals regarding carbon scarcity post-2020. This requires launching the political process on defining the EU’s 2030 climate and energy objectives, including the ETS cap. Clearly this process would be slow and difficult, and would certainly require primary legislation to amend the ETS directive. It has already been proposed to make amendments to the Energy Efficiency Directive, which is currently moving through the co-decision process, to increase the rate of automatic reduction of the ETS cap (currently set at 1.74% per year). They seem unlikely to be adopted; fundamental reforms to this central policy instrument will likely require a dedicated impact assessment and longer political scrutiny. Instead, the Energy 2050 Roadmap process could deliver a request to the Commission to bring forward proposals on 2030 energy and climate objectives. Within this, the ETS should occupy a central position. In parallel, the set-aside option could be advanced, demonstrating to market participants that the EU is coherently addressing short- and long-term weaknesses in the ETS.

These two policy options could be complementary. The set-aside would raise short-term prices but not long-term certainty. A 2030 ETS cap may not immediately increase current carbon prices. Legislating a 2030 cap would take time, and given current market faith in government regulation and high market discount rates, its impact on short-term prices may be limited. In addition, the market is currently so oversupplied that a 2030 cap may not alter demand and supply until towards the second half of the current decade. Therefore, both approaches should be pursued: long-term certainty via 2030 objectives, and if necessary a short-term withdrawal of allowances from the system. Such a combined approach would strengthen the long-term investment incentive, which is the primary objective of the ETS. It would also strengthen the credibility of the regulator, as it responds clearly and logically to this objective.

Finally, in the longer term the EU needs to develop credible processes and institutions to manage the ETS. Emissions trading is inherently volatile, as supply is fixed politically and does not react directly to demand. Any changes in economic output or the political calculus will therefore feed into the price. Managing the ETS is difficult in a polity like the EU, where Member States are reluctant to give up sovereignty over energy and economic policies. This dynamic favours one-off, “big-bang” reforms (most recently in 2008 for the 20/20/20 package), which is not conducive to the efficient management of inherent volatilities in emissions trading. The UK Climate Change Committee and the Australian Climate Change Authority offer examples of the kind of independent advisory institutions that could be considered in the longer-term. While not perfect, the Australian system of a five-year-rolling cap (the cap is set each year x for the year x + 5) could offer an example of an approach that combines elements of flexibility with certainty.

|

About the authors Thomas Spencer (thomas.spencer@iddri.org)is Research Fellow Climate and Energy Economics at IDDRI, Emmanuel Guérin (emmanuel.guerin@iddri.org) is Programme Director Climate at IDDRI. |

Discussion (0 comments)