"Energy is bigger than any single country"

on

Interview: Christoph Frei, Secretary-General World Energy Council

"Energy is bigger than any single country"

The World Energy Council can truly be said to be the United Nations of Energy, bringing together the greats of the energy world. Yet the 89-old institution is not very well known to the outside world. Secretary-General Christoph Frei is trying to raise the relevance and visibility of the WEC - without endangering its unique depoliticized, low-stakes approach to energy diplomacy. EER spoke to him about this balancing act - and the energy challenges facing the world. The key, he says, is inclusiveness. "You need to work with, not against."

|

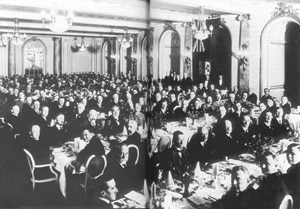

| Official dinner at the first World Power Conference, London 1924 |

Many of you will probably have to admit that you may have heard of the World Energy Council, but are not very aware of what it is and does. And this is strange, for there is hardly a more venerable - or influential - energy body than this institution, dating back to 1923.

Made up of 93 (!) national committees, representing virtually all countries of the world, an Officers Council with top-level executives from around the globe and contacts at the highest political level from China to South Africa and Saudi Arabia to Washington DC, the London-based organisation should be a household name in energy circles and far beyond. Yet, as Secretary-General Christoph Frei admits, when EER speaks with him in his office near Picadilly Circus, this is currently not the case. Indeed, he has asked himself the same question: "When you have so many committed top-level people on board and such a wide reach, how is it possible that our brand recognition is so low?"

The WEC's relatively modest fame is something that Frei, flanked by his Director of Communications Stuart Neil, would like to change - to reflect, as he says, the changing times, in which energy has acquired paramount importance. As former Senior Director for Energy Security, Anticorruption and Climate Change at the world famous World Economic Forum in Davos, the Swiss national Frei, who joined WEC in 2009, certainly seems to have the right experience for the job. In its own area, the World Energy Council is, like the World Economic Forum, the greatest network of the world, but not nearly as well known as the club from Davos. Incidentally, Stuart Neil has an appropriate background as well: he was Press Secretary of the British Queen before he joined WEC. "Same problem", he remarks drily. "Old family."

Off the record

|

| Christoph Frei, Secretary-General of the World Energy Council |

But that kind of trust cannot be very well translated into visibility. "We could be quoted in the Financial Times every day", notes Neil. "But only for a short while."

Indeed, characteristic for the WEC is that, as Frei puts it, it works by "lowering the stakes".

He gives an example. "WEC had a top-level meeting before the famous UN Climate Conference in 2009. We already concluded then that the agenda was not set in the right way and would go nowhere. What we now see is that people are beginning to realize they should throw energy issues at WEC before discussing them at the political level. We are not institutionally strong enough to deliver the process at the political level, but that's what keeps the stakes low. We have practitioners sitting at the table rather than politicians. This makes us the logical place to go to discuss an issue."

The key of the WEC approach, says Frei, is inclusiveness. "You need to work with, not against. Putting pressure on countries like India and China, does not work. And if you don't have those countries on board, you are irrelevant."

Talking shop

That may be so, but if you become too inclusive, don't you run the risk of becoming a harmless talking shop? How much impact does WEC really have?

"That's a tough one", Frei admits. "But", he notes, "I am convinced that based on our inclusive approach, we are able to drive true content. It's our responsibility to avoid populism. When we take a position, you can't get around it."

So how does this process of taking positions work at the WEC? Who speaks when WEC speaks?

Frei explains that WEC has three levels of governance. The fundamental decision-making body is the Executive Assembly, in which every member country is represented with one vote. Frei: "They don't pay the same, but they have the same vote."

Then there is the governing board, called the Officers Council, led by WEC's Chairman, Pierre Gadonneix, former CEO and Chairman of French energy company EdF. And there are the Standing Committees, which oversee the work carried out under the WEC umbrella.

Frei notes that half of the WEC's budget comes out of the country networks, 5% from events and 45% from contributions of "patrons" and "global partners" (i.e. companies) - but the latter, he says, "have no governance power". Those partners range from Siemens to IBM, and from Ernst & Young to Saudi Aramco - 32 in all. "You can apply the law of large numbers here: the larger the number, the more neutral you are."

The actual writing of the WEC reports he describes as a "volunteers' effort". The Standing Committees oversee this work, but delegate it to individual authors. An example is the WEC's report on nuclear power, "Nuclear Energy One Year After Fukushima", published earlier this year. Frei: "Interestingly, this was actually written by a brilliant Saudi economist who is employed by a major international oil company."

Post-Fukushima

Although WEC may not be known for its hard-hitting viewpoints, its post-Fukushima report on nuclear power is certainly not the result of some feeble compromise. In it, WEC concludes unambiguously that nuclear power will continue to expand globally in spite of the Fukushima-disaster. Can we conclude then that WEC is in favour of nuclear power?

Frei: "WEC is convinced that we cannot afford to lock the door to any technology. We believe there are no bad technologies, only bad management. The point is that we are not going to power the world with any one technology, in spite of what any lobby group might say."

But Frei adds that the WEC's message is not as simple as ‘being in favour of nuclear'. "Here is what our nuclear report says. Two-thirds of the world's existing plants is located in four countries: the US, Russia, France and Japan. Three-quarters of the world's new plants will also be built in four countries: China, India, Russia and South Korea. Has Fukushima changed the plans in those countries? Not in China, Russia or South Korea. In India there is growing resistance from the population, but experts say the country can simply not do without new nuclear power plants. Those are the facts. So we conclude that nuclear power will continue. But then we ask: is international governance in place to prevent the next nuclear accident? And our answer is: no, it is not. That's our message. From a German point of view, it may seem pro-nuclear, but from a French point of view, it may look very different."

|

| Greenpeace activists at the World Energy Congress (WEC) in Montreal - © François Parent / Greenpeace |

Energy Trilemma

This raises the question, what is WEC doing it all for? Frei likes to take a historical perspective on this. "When WEC was created in 1923, in the post-World War One period, energy was seen as a key enabler for development. You know the famous quote by Lenin: ‘Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country'. Electricity and energy were very important then. But there was also a growing understanding that energy is bigger than any single country. That there has to be an exchange of technology. In those days, security of supply and technology were more important than the environment. Over time sustainability became a key issue. Our mission has evolved into the goal of promoting the sustainable supply and use of energy for the greatest benefit of all."

The WEC's mission used to be translated into what was called "the four A's": affordability, accessibility, accountability and availability. But under Frei and Gadonneix that has been replaced by the Energy Trilemma: energy security, sustainability and the eradication of energy poverty. "The four A's were not very clear to me", he says. "I see the Energy Trilemma as a sharpening, a further development."

Frei concedes that the Energy Trilemma does not represent any "hard" targets or criteria, but, he says, "it would be very hard to get the world community to agree on absolute numbers. The fact is that there are three groups in society with different priorities: environment, affordability, security. If you neglect one, you will not achieve your goals. The neglected group will step up and kill your plans. The balance is very important. The Energy Trilemma is a unifying principle."

Expertise of industry

After having worked for WEC for three years, Frei gradually sees a "new WEC" emerging, one that makes the work and the huge knowledge base of the organisation more visible. A renewed website that will be launched next year, will open up a treasury of global energy data, promises Neil, based on the WEC's unique global network. All freely accessible.

One thing seems certain: given the huge uncertainties in the global energy regime, there could hardly be a better time for the World Energy Council to come to the fore. You might say: it's now or never. As Joan MacNaughton, a senior adviser of WEC,

| "Something as fundamental as energy requires a long-term approach, not subject to the vagaries of political decision-making" |

One important instrument by which WEC spreads its messages is through its annual "issues survey" of ministers, CEOs and leading experts in over 90 countries: the World Energy Issues Monitor. This publication shows which issues the world's leading energy stakeholders are concerned with, although it does not say what they think of those issues. Frei says he wants to make the Monitor more detailed in future.

As to those energy issues themselves, WEC tracks and traces all the major ones. For example, it has recently issued reports on smart grids and on Global Transport Scenarios. It concerns itself with carbon capture and storage (Frei: "Are we making progress on CCS? No"), shale gas ("a story that has almost been written") and shale oil ("a sensational but largely unwritten story as yet").

One of the biggest - perhaps the biggest - energy challenge today is how to find the huge sums of money needed to replace the ageing infrastructure across the globe, and do this in the face of an increasingly critical public and increasingly volatile political environment. Frei: "You have 65 trillion dollars that's being managed by institutional investors in OECD countries", he says. "Less than 1% of that goes into energy infrastructure. Why is that, when you consider that energy infrastructure tends to give solid, safe returns? Is the sector too complex? Too much exposed to volatility in government decision-making?"

In this context, Frei has an interesting suggestion to solve the problem of regulatory uncertainty. "We have managed to put monetary policy into the hands of an arm's length institution", he says. "But something as fundamental as energy also requires a long-term approach, not subject to the vagaries of political decision-making. Energy investments are long-term, political decisions tend to be short-term. Maybe we should persuade governments to take an arm's length approach to energy as well."

Discussion (0 comments)