Algerian gas – still a key part of southern Europe's energy mix

on

Algerian gas – still a key part of southern Europe's energy mix

As a reliable supplier of natural gas – on which some Southern European countries, particularly Spain and Italy, have grown heavily dependent – Algeria has a long-established position as Europe’s second largest external supplier of natural gas. But there have been some dramatic events in Algeria in the last few months. The sacking of long time energy minister Chakib Khelil and the dismissal of the Sonatrach CEO and several top managers of the national company on corruption allegations coincide with an aggressively pursued export programme now carried out at a time that European markets are awash with natural gas. Furthermore, Algeria continues to find it difficult to interest foreign investors in some of Algeria’s new prospective regions. Algeria’s new energy minister, Youcef Yousfi will have his work cut out not only in housecleaning at Sonatrach in the wake of the corruption scandal, but also in ensuring future gas supplies and defining a new Algerian energy policy.

|

| Chakib Khelil, former Algerian Minister of Energy |

These days, a trip to Algiers is not the intimidating affair that it was in the mid-1990s. At that time, Algeria was close to outright civil war, as insurgents and the security forces engaged in a brutal and murky struggle for control. One of the outstanding achievements of Algerian President Bouteflika’s more than ten years in power has been an enormous reduction in political violence, and while the North African country is by no means yet the world’s favourite tourist destination, business visitors to the capital are again common. The improvement in the security situation has importance to Europe not only from the point of view of the stability of a populous near neighbour, but also because Algeria is one of Europe’s most important energy suppliers. But all is not well in Algeria’s energy sector, however. The sacking last month of the long-serving energy minister Chakib Khelil came on top of a remarkable corruption scandal which led to the arrest of the CEO and several other senior managers of the state-owned oil and gas giant Sonatrach.

Important supplier

Algeria is a significant producer of crude oil – in 2009 production averaged some 1.8 million barrels/day – but the country’s strategic importance for Europe rests mainly on its position as a gas supplier, particularly to southern Europe. And while Algeria’s 51 Bcm of gas exports to Europe in 2009 were less than half of Russia’s 133 Bcm, Sonatrach is a more important gas supplier than Gazprom in southern Europe. Indeed, concerns over Algeria having too dominant a position prompted Spain to pass legislation in 1995 which limits any external supplier’s share of the Spanish market to no more than 60% - a level which is no longer in threat as other suppliers of liquefied natural gas (LNG) have progressively stolen Sonatrach’s market share in Spain over the years.

And gas is particularly important to Algeria. Natural gas makes up some 48% of Algeria’s total hydrocarbons production in energy terms, but its significance to Algeria goes beyond this. While Algerian oil production started up during the period when the country was under French rule, the first LNG exports came in 1964, two years after independence, and was one of the early achievements of the new state. Algeria was in fact the founder of the global liquefied natural gas (LNG) trade, being the first commercial exporter of LNG, with the UK being its first customer(these were the days before the discovery of North Sea gas). The development of the Algerian gas business – and the parallel growth of Sonatrach, which was established in 1963 – are therefore major sources of nationalistic pride in Algeria.

But the development of Algeria’s gas industry has not been all plain sailing, by any means. A planned major expansion in LNG output in the late 1970s went awry when falling US gas prices made LNG imports unattractive, causing buyers to pull out of long term contracts they had signed for the import of Algerian LNG. Algeria was left with a heavy debt burden, and LNG facilities that operated below their full capacity until into the 1990s. But despite the troubled early history of the LNG business, Algerian gas production grew steadily, aided by pipeline gas exports first to Italy, and then to Spain, and rising from 14.2 Bcm in 1980 to 49.3 Bcm in 1990.

The 1990s were difficult years for Algeria, as politically-inspired violence spiraled out of control following the cancellation in 1992 by the military of legislative elections which the FIS (Front Islamique du Salut), an Islamist party, was poised to win. By the mid 1990s the insurgency had reached a level which gave European countries serious concerns over reliance on Algerian gas. But despite a chaotic internal situation, and the loss of perhaps 100,000 lives in the violence, there were surprisingly few attacks on the oil and gas facilities, and no serious disruptions to gas exports.

Chakib Khelil

Abdelaziz Bouteflika – a veteran of the Algerian war of independence – was voted to power as president in 1999, and immediately set about putting in place a process of reconciliation which, while it has not by any means eliminated political violence in Algeria, has at least pulled the country back from the brink of chaos. But in addition to tackling the security problem, Bouteflika made a surprising choice for the post of energy minister, bringing into the job a former Sonatrach executive named Chakib Khelil who had spent the last 20 years or so in the World Bank in Washington – much of his work having been on energy sector reforms in Latin America.

And Khelil at first appeared likely to be a radically reforming minister. He proposed a series of reforms aimed at liberalizing the domestic energy market and changing the status of Sonatrach - turning it from an arm of the state into a fully commercial company. He went as far at one stage as to suggest that Sonatrach might one day be privatized, but this proved to be at least one bridge too far, and a strong public reaction made Khelil back-track on the privatization issue.

In fact, Khelil’s initial liberalizing tendencies and open approach faded away progressively over his tenure of just over ten years in office – easily a record for an Algerian energy minister. The centre piece of his reform package – a new Hydrocarbons Law to replace that dating from 1986 – had its provisions watered down before it was finally passed into law in 2006 after vigorous opposition both from the media and from inside Sonatrach itself. In its final form, the law contains provisions that ensure that Sonatrach remains in the driving seat in the Algerian industry, including allowing it to maintain control over Algerian gas developments.

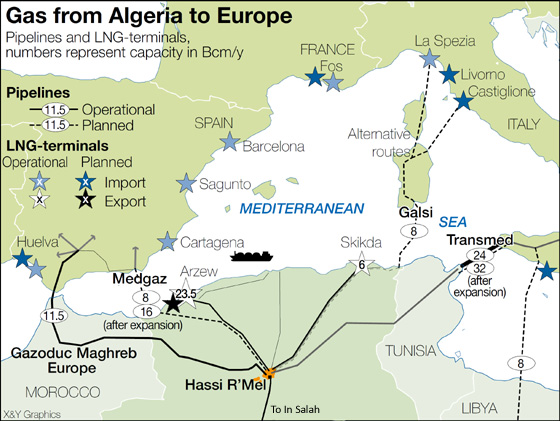

Khelil also put in place an ambitious new target for Algerian gas exports. From the level of around 60 Bcm/year which they had reached by 2000, Khelil set a new goal of 85 Bcm/year by 2005. This level would be reached by investing in new export infrastructure: the expansion of existing export pipelines, a new direct gas pipeline to Spain (Medgaz), another to mainland Italy via Sardinia, and a new LNG facility at Arzew. But this target had to be put back progressively for various reasons. The plans for an expansion in LNG capacity ran into trouble as a devastating explosion and fire in 2004 destroyed three liquefaction trains at Sonatrach’s Skikda facility. And after the Skikda disaster, controversy surrounded plans to build a new LNG plant at Arzew, as Sonatrach rescinded a contract it had signed with Repsol and Gas Natural for the construction after the Spanish companies tried to renegotiate the terms under which they had been awarded the concession. With the setbacks to LNG expansion, Khelil’s 85 Bcm/year goal will not be reached until 2013 or 14.

|

| The Hassi R'Mel production centre and its outlet infrastructure. Natural gas from the southern In Salah production region is also fed into the system at Hassi R'Mel. |

But in fact the delays to the expansion of pipeline and LNG export capacity may conceal a further problem: namely a shortfall in gas availability. Algeria’s gas production is built around the output from the super-giant Hassi R’Mel field, which contains around half of Algeria’s proven gas reserves. Hassi R’Mel functions as a “hub” for the Algerian gas system, with production from fields to the south routed to Hassi R’Mel for redistribution to the north. Hassi R’Mel produces valuable amounts of condensate (light crude oil) together with gas, and in order to maintain production of the condensate, around 60 Bcm/year of production must be recycled back into the Hassi R’Mel reservoir to maintain pressure. The need to maintain condensate production places a limit on Hassi R’Mel production, which means that further expansion of gas production must come from elsewhere, and the province that Sonatrach has had its eyes on for some years is the area to the south and west of Algeria, in the deep Sahara.

Gas fields around In Salah, some 500 km to the south of Hassi R’Mel, were discovered in the 1950s, but after the Hassi R’Mel giant had been found there was no need to develop these more distant and difficult fields. But by the early 1990s, with the restrictions on Hassi R’Mel production becoming obvious, Sonatrach looked again at development of the In Salah fields, and, following long and tortuous negotiations, signed a deal with BP in 1995 for the development of 9 Bcm/year of production from the In Salah fields and the construction of a new gas pipeline connecting the fields to Hassi R’Mel.

|

| A natural gas production field at In Salah in central Algeria |

Several projects now seem close to realization, all led by European companies who are keen to grasp the opportunity to be involved in upstream developments which, potentially at least, link to their downstream positions. Total/Cepsa, GDF Suez and Repsol/RWE/Edison are all pressing ahead with developments in the region, and in January this year it was announced that Total and Partex had been awarded a contract for development of the Ahnet fields, directly to the south of In Salah. Ahnet has the potential to produce around 4 Bcm/year at plateau, and the rights to develop the fields in partnership with Sonatrach had originally been offered as part of the first licensing round held under the new hydrocarbons law. But the arrangements proposed proved too complex, and the perimeter had to be remarketed.

So, although the programme for development of the south-western fields has suffered several delays, it now seems that Algeria will have the gas production to back up the increase in exports which will result when new LNG capacity comes on stream in 2013, when Khelil’s 85 Bcm/year target should finally be met.

Youcef Yousfi

But since Khelil set this target, profound changes have taken place in the European gas markets. Spain was severely hit by the recession, resulting in a 10.3% drop in gas consumption in 2009. In view of the drop in demand it is not surprising that the new Medgaz pipeline from Algeria to Spain, has seen its start-up date slip – ostensibly for technical reasons – to the latter part of this year. And other markets saw similar, though less dramatic drops in consumption.

The recession-induced reduction in European gas demand will reverse, but Europe is likely to remain structurally over-supplied with gas for some time to come. The main external suppliers – Sonatrach and Gazprom – have more than enough capacity for the market needs and with the huge expansion of LNG production from Qatar coinciding with low US gas prices, there is likely to be a surge of LNG seeking a more profitable outlet than that provided by the US Henry Hub gas price. And looking longer term there are the prospects of competition from new pipeline gas from the Caspian and Middle East, and beyond that again there is the potential for Europe to follow the US in a boom in shale gas production.

So Algeria’s coming boost in production may be badly timed. With the European markets likely to continue to be long in gas for some time, price-based competition is bound to increase, threatening the structure of long-term (20 year plus) contracts with prices linked to oil. For most of this year traded gas prices in North West Europe have been running $2-3/MMBtu below the long-term contract prices.

The prospect of a downward spiral in European gas prices will be very worrying for Sonatrach, most of whose gas is sold on long-term oil price-linked contracts, and will pose a difficult strategic problem for new energy minister Youcef Yousfi.

Algeria has always been one of the staunchest supporters of long term contracts, and was a vehement critic of the European Commission’s approach to the gas markets at the time the first Gas Directive was enacted in 1996. And despite his previous World Bank incarnation, Khelil largely held this line. Youcef Yousfi is a man very much steeped in the background of the Algerian oil and gas industry – he was one of the architects of the 1986 hydrocarbons law when he was head of Sonatrach, and he preceded Khelil in the post of energy minister. Yousfi is therefore – and probably rationally – more likely to seek to defend the interests of suppliers using whatever leverage he can muster, rather than embrace market restructuring as an opportunity.

One thing that Yousfi may choose to do is to press harder to make the Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF) behave a little more like OPEC, in an attempt to exercise collective power on the gas markets. Algiers has been chosen as the location for the secretariat of the GECF, and the Forum’s last ministerial meeting was held in Algeria, coinciding with the ill-fated LNG 16 congress in Oran in April, which saw delegate numbers drastically reduced following air travel disruptions caused by the Icelandic volcanic ash cloud. Algeria is rumoured to have lobbied for a strong statement on coordinated action at the Oran meeting, but the actual communiqué was very brief and distinctly less than volcanic, commenting only that "ensuring adequate and reliable supplies of gas at prices reflecting parity with oil prices and the advantages of natural gas is a challenge."

A challenge it undoubtedly will be, adding to several other challenges that Yousfi faces. The most urgent among these will be reacting to the corruption allegations surrounding the previous CEO of Sonatrach, Mohammed Meziane, and several of his top team and restoring faith in the sector. Already Yousfi has moved to introduce new rules governing the award of engineering and procurement contracts – the area which seems to be implicated in the corruption charges. But perhaps his biggest long-term challenge will be to stimulate enough continuing upstream activity to provide a flow of gas developments which will maintain the desired level of exports, as well as catering for the needs of a growing domestic market.

Yousfi apparently intends to go ahead with a new licensing round before the end of the year, and it will be interesting to see if he is more successful in attracting foreign exploration dollars than his predecessor. And Europe is not simply a disinterested observer of this scene. A balanced relationship with Algeria, and a continuing flow of investment into gas projects is, and will remain for some years, an important - although patchily achieved in the past - aim of Europe’s energy security policy.

| David is Managing Consultant at Gas Strategies. He specialises in the Southern European and Mediterranean energy markets and in LNG. Before moving into consultancy David held a number of senior posts with BP’s upstream business where he was responsible for BP’s Southern European gas marketing and took a leading role in establishing the In Salah Gas joint venture in Algeria. |

Discussion (0 comments)