Britain’s electricity sector headed for a cliff edge

on

Liberalisation called into question

Britain’s electricity sector headed for a cliff edge

Britain is careening towards a ‘cliff edge’ when it comes to generating enough electricity to meet demand post-2015. That was a major conclusion of a report published last month by regulator Ofgem. It urges rapid action to ensure the looming generation gap is bridged. The British government faces tough choices: it has huge climate ambitions – but cannot let the lights go out. The big question is whether and to what exent the government will intervene in the free electricity market.

|

| UK energy minister Ed Miliband |

| Highlights of the debate |

|

- Market regulator Ofgem: ‘There is an increasing consensus that leaving the present system of market arrangements and other incentives unchanged is not an option’ - Professor Jonathan Stern: ‘For me the key thing is that the era of free energy markets in the UK has passed. Liberalisation has finished. We’re going back to more intervention, more central direction, more government decisions and fewer market decisions about what’s going to be built.’ - David Porter, chief executive of the Association of Electricity Producers: ‘The companies see the need to invest. But it’s not as easy to make investment decisions as it should be, partly because of the carbon market not providing the steer that some companies would like. We’ve said over and over again that it’s vitally important that the UK should present a political and regulatory environment that makes it attractive to invest.’ - Stern: ‘If you believe that Miliband’s low-carbon transition plan is possible, then fine. But I haven’t found a single person who believes it’s possible to build renewable capacity at that rate. So all we can see happening is a lot more gas-fired generation.’ - Porter: ‘It leaves us with gas and offshore wind’ |

In its Project Discovery consultation paper released last month, UK energy regulator Ofgem concludes that if demand grows as expected, Britain faces a yawning gap between the electricity it will need and the amount it will be able to generate in the second half of this decade. It is unthinkable that the government will, to use the current buzz-phrase, allow ‘the lights to go out’. But many commentators, including energy regulator Ofgem, believe urgent reforms are needed to ensure the necessary investment in new plant is made. The government’s answer to these concerns will be announced on Budget Day – 24 March – less than two weeks from now. The energy sector is eagerly awaiting its announcements.

Fairly mad

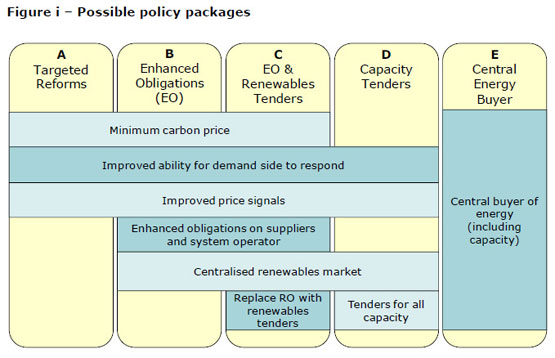

Ofgem has plenty to say in its report about the government’s possible options. It presents five policy packages that the government could choose from to implement electricity market reforms (see chart at the bottom). They range, in the words of one industry source, from the ‘fairly mild to the fairly mad’.

Launching the consultation paper, Ofgem’s chief executive, Alastair Buchanan, said: ‘Britain has a window of opportunity to put in place far-reaching reforms to meet the potential security of supply challenges we may face beyond the middle of this decade. We do not advocate change lightly . . . There is an increasing consensus that leaving the present system of market arrangements and other incentives unchanged is not an option. Ofgem has therefore put forward a range of possible options to unlock the £200 billion of investment Britain may need.’

At the ‘mild’ end of the spectrum are ‘targeted reforms’: a minimum carbon price to encourage investment in low-carbon generation; stronger encouragement for demand-side response from energy users through better price signals; and sharper signals in the gas and electricity wholesale markets to encourage suppliers to ensure they have better access to back-up supplies, especially at times of high demand.

At the ‘mad’ end of the spectrum is an eyebrow-raising proposal to establish a central buyer of energy and capacity that would determine the amount and type of new electricity generation needed, and could also tender for new gas infrastructure.

What prompted Ofgem to come up with so radical a set of proposals? ‘We were aware that the energy industry was facing an unholy trinity of challenges: the credit crisis, tough environmental targets, and increasing gas dependency,’ an Ofgem spokesman told European Energy Review. These factors have combined ‘to cast reasonable doubt over whether the current energy arrangements will deliver secure and sustainable energy supplies’.

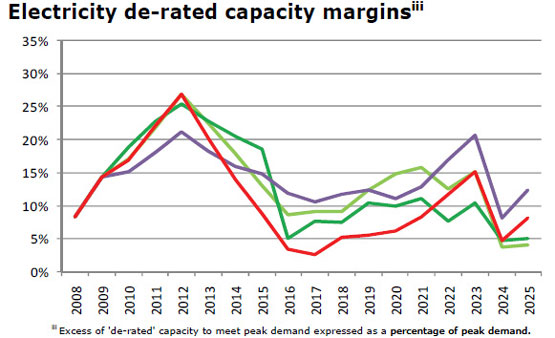

Ofgem has therefore joined those who worry that a generation gap will open up beyond 2015. ‘We refer to it as the “cliff edge”,’ said the spokesman. ‘There is an excellent illustration of this in the scenarios document that we published last October [see the chart on capacity margins]. It shows how capacity margins will change in electricity. We have a comfortable few years ahead of us – and this is part of our argument: we need to start to act now to mitigate that cliff edge. Our four scenarios have different implications for the cliff edge, but everyone accepts that that cliff edge is looming nearer.’

|

|

|

|

Capacity margin is an indication of how robustly an electricity system is likely to be able to meet demand peaks. It is a measure of how much extra generation capacity there is on the system than would be needed to meet expected peak demand, such as during an average cold spell. |

What about the concept of a central energy buyer? Isn’t that undoing two decades of liberalisation and boosting competition? ‘What we’re saying to government is here is a range of possibilities, from targeted reforms of markets to – if you want a firmer degree of certainty – a central energy buyer. Now this isn’t nationalisation. This could be carried out by National Grid. There are pluses and minuses to all the proposals. It’s not Ofgem’s role to make the decision. It’s the government’s job to determine energy policy.’

More intervention

The view of Professor Jonathan Stern, of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, is that: ‘Ofgem felt it was important to go through the different options. If you’re looking at options you should really look at leaving it to the market as against all the other options, including reinstating a central buyer like the CEGB [the Central Electricity Generating Board that existed pre-privatisation].’

‘For me the key thing – from all the noises coming out of government – is that the era of free energy markets in the UK has now passed. Liberalisation has finished. We’re going back to more intervention, more central direction, more government decisions and fewer market decisions about what’s going to be built. And that is being driven by a carbon agenda and not an energy agenda.’

Overall, the industry’s responses to the Project Discovery initiative suggest that the big generators do not feel that the market is failing. They worry that the government may intervene in a way that is less than helpful, instead of creating the conditions that will actually facilitate investment in new generation plant.

‘The general consensus is that we have a problem in making investment decisions that shouldn’t exist,’ says David Porter, chief executive of the Association of Electricity Producers. ‘The companies see the need to invest, partly because of the closure of a lot of plant and partly because of the green agenda, in particular last year’s Renewable Energy Directive from the EU. But it’s not as easy to make investment decisions as it should be, partly because of the carbon market not providing the steer that some companies would like. They want to follow the green agenda but they need more clarity. We’ve got to know that politicians really mean it about carbon. The only way that will come through is with a meaningful price for carbon emissions.

‘Potential investors also want to be sure that government policy is steadfast and long-term. We need to see a commitment to keeping policy stable. For example, we’ve seen attitudes to nuclear power change 180 degrees in the space of just a few years. We were pleased with the outcome of that – but only three years before government saw little future for it. Changes in policy of that kind send out a signal to the world and it’s not always a helpful one.’

Nor have the financial crisis and the global recession been helpful. ‘It’s not as easy to raise money as it used to be,’ says Porter. ‘Added to that, the UK’s not the only place that needs investment in energy infrastructure. Resources are not infinite and people will compete to offer the best deals. We’ve said over and over again that it’s vitally important that the UK should present a political and regulatory environment that makes it attractive to invest.’

Disappointing

Sara Vaughan, director of regulation and energy policy at Eon UK, one of the country’s largest electricity generators, stresses that Eon remains committed to competitive and liberalised markets and would like the government to do the same. ‘We believe that the market has delivered in the past and is continuing to deliver across much of Europe’, she says.

‘However, there have been some changes as a result of interventions: the 20:20:20 EC target, which has been translated in the UK to 15% of energy from renewables by 2020; and the Committee on Climate Change targets to de-carbonise the system by 80% by 2050. These are making a big difference to the market.’

Eon would like to see a strengthening of the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). ‘We believe the ETS is the right way to promote de-carbonisation of the economy,’ says Vaughan. ‘But there is an issue with the ETS in that it doesn’t have a long-term target in it. An effective long-term volume cap beyond 2030 would drive a more robust price. Copenhagen was clearly disappointing. In light of that and in a country like the UK that has decided to move quickly towards decarbonisation through its own internal targets, it looks as though something further will be needed. So we’re hoping to see the government’s continued commitment to dynamic markets – alongside an acceptance that those market frameworks need to change to deliver the investment that’s needed.’

A lot more gas

There are questions also over how feasible are the government’s climate change targets for 2020, given that that is now only a decade away. Moreover, the low/zero-carbon generation technologies the government is pushing for – renewables, nuclear, and carbon capture and storage (CCS) – are seen by many as highly unlikely to bridge the looming generation gap in time.

|

| Jonathan Stern, gas programme Director at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies |

Nor will nuclear come to the rescue. The government and the companies working to build new nuclear power stations in Britain hope the first plant will come on stream by 2018. But industry insiders privately concede that this is highly optimistic – more likely is that the first plant will come on stream sometime after 2020. Besides, even 2018 is too late to bridge the gap.

As for CCS, it is such a new and challenging technology that there is a consensus that the best that can be hoped for by 2020 is a handful of demonstration plants.

What options does that leave? ‘It leaves us with gas and offshore wind,’ says David Porter, though he admits that the intermittency of wind-power means that it needs back-up from less uncertain generation sources when the wind isn’t blowing. That too raises controversial issues. ‘There needs to be a more serious debate about the nature of that back-up,’ says Porter, ‘because we’re going to have more gas-fired power stations built. It is those that will keep the lights on and will overcome some of the difficulties that you see in the more sensationalist headlines. The role of those stations might change over time, depending on how much offshore wind gets built, and when. There is an issue about how you remunerate plant that doesn’t get used very often.’

Doubts about back-up

Views in the industry are not unanimous. ‘We have members that see a need for building plant specifically to back up offshore wind and we have others that see a more imaginative use of what by then will be existing gas plant,’ says Porter. ‘The doubts about back-up power are part of the difficulty that companies face when they’re contemplating new power station investments – not just from the point of view of a company thinking of building a wind farm or a company thinking of building back-up for a wind farm, but for everybody. Because all this has a bearing on their expectations of capacity margins, demand and therefore prices.’

Porter regards it as ‘very unlikely’ that we will actually see the lights going out. ‘We’ve got quite a robust, still fairly diverse, and quite sophisticated integrated power system. Added to that we have companies that have new power projects on the stocks. They’re mostly renewables and – importantly – gas. There is a question about how dependent we might become on gas. Views in the industry are not united on that issue. It’s fair to say that a number of companies would have been interested in building new coal-fired power stations to reduce their dependence on gas. But that’s been made more difficult than it was a couple of years ago. Having said that, there’s been a lot of investment in gas infrastructure: pipelines, storage, and port facilities for imported LNG. And there’s more to come.’

On the issue of gas infrastructure, Porter, Stern and Ofgem are united. ‘One of the big success stories over the last five or six years is the huge expansion of LNG regasification facilities in the UK,’ says the Ofgem spokesman. ‘The vulnerability is down to price. When oil prices rise, we’ve seen that consumers face steep rises in their energy bills. Obviously, the more dependent you become on one fuel the more vulnerable you are to fluctuations in oil and gas prices.’

Where they differ is on the question of how dependent we should allow ourselves to become on a single fuel, especially when much of Europe’s gas comes from Russia, given the events of January 2009, when supplies to Europe were interrupted by a dispute between Russia and Ukraine. ‘We have some members that would say we cannot afford to become any more dependent on gas while others would say “grow up, it’s actually easier to get than you’re implying”’, says Porter. ‘I would admit that there is concern among many companies in the industry about overdependence but it’s not a unanimous view.’

Impossible to deliver

Professor Stern’s view is that worries about gas dependence are overdone. ‘The one thing you have to say is that January 2009 happened. If you’d said to me could all gas coming through Ukraine be cut off for two weeks in the middle of winter, I would have said “no that can’t happen”. That means the Russians have exposed themselves to the accusation – whether it was fair or not – that they are not a secure supplier. There are those of us who believe this is a transit issue, which was about a commercial and political disagreement with Ukraine. And there are those – particularly in the UK and the new member states – who believe that this is the Russian government using energy as a political weapon. Those who believe that are not going to change their minds any time soon because their view is basically “this is a nasty evil country, run by nasty evil people, who are trying to wage war on Europe and are going to use anything they can”. It’s not a view I agree with but it’s a view I understand.’

Gazprom’s response to the Project Discovery initiative has been to insist that it is doing everything necessary to meet its commitments, including building major new pipelines that will circumvent Ukraine. And, besides, Britain’s vast LNG importation infrastructure means it could source gas from a wide variety of producers.

So what should the government decide on Budget day? ‘Miliband should hedge his bets by repeating the low-carbon energy strategy and saying this is what we’d like to do,’ says Stern. ‘And then say there are doubts that this is going to be possible, because of the difficulty of building such a huge amount of renewable capacity so quickly. And if that proves not to be possible, the fall-back is gas. It would be good for his credibility if he recognised that in public. I don’t think he’s doing himself or the government any favours by putting forward a strategy that is widely regarded as impossible to deliver. We can all agree that carbon reduction is the right aspiration – but it’s important to get some sort of reality as to how quickly that can be done.’

| According to Professor Peter Odell, the UK could do a lot more to boost its domestic gas production. To read his call for a more interventionist oil and gas policy in the UK, click here. |

|

| Ofgem's proposed policy packages for the UK's energy sector |

Discussion (0 comments)