Desert Powered Progress

on

Desertec can integrate the EU with North Africa and the Middle East on many different levels

Desert Powered Progress

The technical, economic and political obstacles to the famous Desertec vision are considerable. It seems much simpler to increase renewable energy production inside the EU without making ourselves dependent on external sources. Yet energy and climate policies should not be the only considerations when we think of Desertec, argue Oliver Gnad and Marcel Viëtor. When viewed from a geopolitical, strategic viewpoint – as a key integration and political project that can bind together Europe with the MENA region (Middle East and North Africa) – Desertec can be part of the answer to many of Europe’s long-term challenges, ranging from migration to economic growth and dependence on fossil fuels. It is time to bring Desertec to the highest political level in Europe: under the aegis of Lady Catherine Ashton and the European External Action Service.

|

| 'It is time to bring Desertec to the highest political level in Europe' |

In March 2009, the Desertec Foundation presented its answer: a concept by which half of the world’s electricity needs would be met by renewable energy sources by the year 2050, relying especially on solar thermal plants in desert regions. The concept builds upon the Trans-Mediterranean Renewable Energy Cooperation (TREC), the solar electricity initiative of the Club of Rome, and basic research done by the German Aerospace Center (DLR).

Almost at the same time, the newly established multilateral Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) also adopted the TREC vision. Calling it their “Mediterranean Solar Plan” (MSP), the UfM launched the first pilot project of a pioneering Mediterranean cooperation. It was intended to breathe new life into the paralyzed Barcelona Process while at the same time opening a new chapter in European energy policy. But since the Gaza conflict of 2008/2009, numerous Arab states have refused to collaborate with Israel, which is also a member of the UfM. Since then, the MSP has lost momentum and the Union for the Mediterranean has been treading water.

In July 2009 an industrial consortium dominated by German companies, the Desertec Industrial Initiative (Dii), banded together to examine the Desertec concept’s technical feasibility in North Africa. Companies in France and Spain have also pooled their resources for this purpose.

These types of initiatives are long overdue. In the long term, the European Union, and especially Germany, intends to satisfy a significant share of its electricity needs from renewable sources, and importing from sunny neighboring areas like the Maghreb region is particularly attractive.

“Feasibility” is the current buzzword, and the sole aim of all parties involved seems to be to construct solar, photovoltaic, and wind power plants in North Africa or build the first functioning high voltage direct current (HVDC) transmission lines in the European Union as quickly as possible. This is actually

| The Desertec concept has the potential to become a "grand design", a "Mediterranean Solar Union" of supranational dimensions |

Notwithstanding this substantial progress in infrastructure, Desertec is far from being “on line.” The technical prerequisites, and especially the general political and social conditions, are still not fulfilled.

Technical Challenges

Only around three percent of the power produced in the European Union is traded across borders—mostly on the “local border traffic” scale. Electricity markets are still economic protection zones. And if EU member countries have their way, this will remain so for the foreseeable future.

The safeguarding of Europe’s domestic markets for electricity is currently the greatest barrier to trans-Mediterranean energy cooperation. Therefore, the challenge for EU member countries is to open up national electricity markets in the EU and to harmonize them by eliminating competitive distortion.

This harmonization would require basic infrastructure that is not yet ready. Cross-border trade in electricity requires an intelligent European grid that can receive and transport dramatically fluctuating amounts of eco-electricity from thousands of small plants (also know as a smart grid). This would also require countless substations for adapting the different frequencies of national electricity grids, masses of inverter modules for AC to DC conversion, and adequate storage capacity—in the form of pumped storage facilities, electric vehicle fleets, or power-to-gas plants, for example.

In order to tackle large-scale infrastructure, measures that require precise harmonization, spatial planning, and plan determination procedures— such as designating the routes for high voltage transmission lines—will have to be streamlined. The German Energy Agency (dena) estimates that Germany alone will require at least 3,600 km in new energy routes, but in the past five years the country

| In the long term, the costs of "business as usual" will be much higher than those of new policies for the joint organization of mutual dependencies |

Financial challenges must also be considered. For example, according to EU Commission estimates, member countries will have to invest 1 trillion euros for infrastructure expansion in the energy sector in the next 10 years. The German government’s forecast says that Germany alone will have to invest 20 billion euros a year in the energy sector for the next four decades. Desertec, with estimated financial needs of 400 billion euros by 2050, has not yet been included in the calculation.

But regardless of the role that Desertec will play in supplying Europe with energy in the future, the EU will have to jump these technical, political, and societal hurdles anyway because they are indispensable for the comprehensive expansion of renewable power production within the EU. The challenges on this list are great enough, but Desertec tops them all. When companies have to make decisions on foreign investments of this magnitude, their risk has to be hedged for the long term.

Political Problems

What kind of investment risk does Desertec entail and how can it be minimized? The first issues are the medium- and long-term environmental conditions and the (security) policy framework in the MENA region. These are not questions that can be answered with any certainty, certainly not in the near future. Then, do the lessons learned with regard to the operation and maintenance of existing large solar thermal plants (e.g. the Mojave desert in Nevada/California or Almeria in Andalusia) also apply to extreme geographical locations like the Sahara? Pilot plants will be used to analyze this soon, but there is no long-term data available yet (meaning that experience-based calculations on electricity pricing are impossible).

|

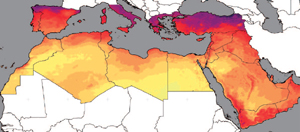

| The MENA region |

This leads us to the prerequisites for regulatory policy, infrastructure, and institutions that cooperation in the energy sector between countries in the MENA region or within the EU would facilitate. However, with a few exceptions (e.g. in Morocco or Egypt), these countries have a long way to go. Regardless of all the efforts directed at cooperation in the Mediterranean region in the past 15 years as part of the Barcelona Process, we need to soberly face the fact that we lack the basic institutional and procedural prerequisites for structural cooperation between the European Union and the MENA region.

Home Grown Potential

In light of the significant risks and objections on both sides of the Mediterranean, we have to ask why the Desertec initiative even needs to be driven forward? Should we not assume that we will be able to satisfy most of our energy needs by consuming less or producing renewable energy within the EU, entirely free from external dependency and risks?

Germany, for example, has ambitious energy efficiency targets. By 2050, 80 percent of its old housing stock (approx. 12 million units) will have to be renovated to save energy and by 2020, new buildings in Germany will be built in a climate neutral way. Through these measures alone, the German government believes it will double the country’s energy efficiency compared to 1990. This takes advantage of the immense potential of the existing infrastructure.

And in the area of energy production, the European Renewable Energy Council (EREC) believes it will be possible to generate two-thirds of the EU’s electricity from renewable sources within the EU by 2030 and 100 percent by 2050. After all, the output of conventional wind farms and photovoltaic plants is

| A project of this importance requires the boss's attention |

So, why do we need electricity from the desert?

A “Mediterranean Solar Union”

The answer is simple: Energy and climate policies are not the only aspects that should be considered when looking at the Desertec concept. Of course Desertec should initially be measured against technological and economic criteria. But at the same time, the concept should be discussed as a key integration and geopolitical project. The Desertec concept has the potential to become a “grand design,” a “Mediterranean Solar Union” of supranational dimensions.

Just as in its day the European Coal and Steel Community was the integration policy core of a Western Europe in the process of economic and political reconstruction, today the green energy sector could serve as an instrument for organizing the mutual dependencies of the countries on both sides of the Mediterranean. On both sides, the future survival of society will primarily hinge on the issue of a sustainable energy supply.

The green tech industries in the EU and the growth societies in the MENA region could exploit comparative technological and geographical advantages to their mutual benefit if they mesh their energy policies. They could tackle together the structural tasks this would require. These include opening the electricity markets in the EU-MENA region and creating structures for real cooperation and competition and models for innovative policy management (a feed-in tariff law, regional funding measures, structural adaptation programs, twinning models, etc.). And they could develop comprehensive added-value chains with local production and development industries and create sustainable jobs. All of this would be supported by an intelligent network of modern financing systems—from microcredit to consortium solutions, and from foreign direct investment and forms of market capitalization to mezzanine and public/private joint financing.

In the MENA region, the implementation of innovative technologies could also create an incentive structure for far-reaching educational policy measures, and an improved education system could boost the position of socially marginalized groups and ethnic groups. In addition, the problem of drought and the associated food shortages could be overcome by developing solar-powered desalination plants. These spillover effects would improve the security of the people in the MENA region and create opportunities for personal development, which would in turn reduce pressure on the EU caused by migration.

Viewed in this light, Desertec becomes the key project of a comprehensive neighborhood policy and a European-level planning task that covers all areas of society. The timing could hardly be better: The upheaval in North Africa is opening up the chance to create innovative forms of inter-societal

| Is a high level of energy dependency on a region that is historically characterized by authoritarian regimes advisable? |

But the European Union has no other choice. It can no longer postpone urgent strategic issues, whether pertaining to economic growth and political participation in the neighboring southern countries, the unsolved problem of migration, the race for natural (fossil) resources, or free trade. In the long term, the costs of “business as usual” will be much higher than those of new policies for the joint organization of mutual dependencies.

EU Interests in the Mediterranean

The current annus mirabilis in North Africa should inflame a discussion on the opportunities and limits of a long-term European policy of interests in the Mediterranean. The EU should quickly find the ways and means to create a European neighborhood policy that does not inevitably lead to the expansion of the Union but nevertheless provides for reliable partnership and an equitable distribution of the benefits of cooperation. Desertec would be an ideal pilot project.

But the Desertec vision, which took center stage as a comprehensive development concept for the EU-MENA region two years ago, is now being discussed mainly from the viewpoint of technical and economic feasibility. The discussion, which is now being led by national special interests and lobbies, urgently needs to be expanded into a fundamental debate on future development scenarios that could go hand in hand with an integrated policy in the EU-MENA region. The process should move step by step with a few particular milestones in aim, and should be under the aegis of Lady Catherine Ashton and the European External Action Service.

|

| Concentrated solar power |

Second, with the inclusion of the relevant organizations involved in international cooperation, the EU should step up its work on competency and capacity development in the MENA countries. This capacity development relates to political requirements as well as economic and scientific skills and the capacity to implement them. A coordinated, coherent approach is essential for success.

As the nucleus of a Mediterranean Solar Union, the Mediterranean Solar Plan should receive a quick political upgrade. The MSP office in Barcelona (as part of the UfM office) is now operative and has developed a roadmap. It needs insistent political support in order to fully tap this institution’s potential during the difficult transformation phase.

A project of this importance requires the boss’s attention. It should not be entrusted to the paralyzed Union for the Mediterranean, exposed to the divergent interests of different areas of authority, or be handed over to an industry consortium. Visions that affect society as a whole—especially a common European vision, which is able to replace financial transfer payments as a substitute for policy—need to receive political priority. Thus at center stage for Europe needs to be a reorientation of its bilateral and multilateral development cooperation, along with a revamping of EU policies toward the southern neighbors, especially its trade and migration policies.

|

OLIVER GNAD* is the head of GIZ AgenZ at the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. MARCEL VIËTOR is a resident fellow at the German Council on Foreign Relations. He focuses on energy and climate policy. *The opinions expressed in this article reflect the personal opinions of the author. This article was first published in IP Global, the Journal of the German Council on Foreign Relations. For this and other articles on energy and the environment see here. Related articles on European Energy Review Desertec sees positive side to political change |

Discussion (0 comments)