EU policy drives Turkey in the arms of Russia

on

EU policy drives Turkey in the arms of Russia

The European Union’s attempts to turn Turkey into an energy corridor to reduce its dependence on Russian imports has only been partially successful. The main problem is that the EU takes insufficient account of what drives Turkish external energy policy. If Brussels and the European countries continue on this road, the Turks are likely to deepen their already close energy relationships with Russia, frustrating Europe’s attempt at diversification, warns Yurdakul Yiðitgüden, a former Turkish Under-Secretary of Energy and Natural Resources .

|

| Pipelines crossing Turkish territory, like the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline in this picture, will increasingly fuel European energy demand. |

True enough, Turkey has historic relations with most of the Islamic countries and has intensified its economic and political relations to these countries in recent years. However, according to some political analysts, even more likely is a grand alliance between Turkey and Russia in the future. Russia, with its vast resources, and Turkey’s dynamic industry and young population may contribute to one another’s prosperity. For Turkey, Russia is also its principal energy supplier, as it is for the EU. Intensified energy cooperation between Russia and Turkey therefore makes considerable sense for Turkey.

For the EU, however, it may have two main consequences: on the one hand, it may help to increase gas volumes flowing to EU countries, while, on the other hand, it may harm the EU’s efforts to diversify its gas imports.

Thus, if the EU really wants to reduce its dependence on Russia, it would be well advised to deepen its energy cooperation with Turkey. So far, the policy of the EU towards Turkey has probably done more harm than good.

Turkish external energy policy

To begin with, there seems to be a lack of understanding in the EU of what drives Turkish energy policies. It is true that Turkey, as everyone knows, tries to establish itself as an energy hub between Central Asia and the Middle East on the one hand and Europe on the other. But this is only a secondary goal of its energy policy. Its primary goal is to enhance its own security of supply. Like the EU, Turkey is becoming increasingly dependent on energy imports while it finds its energy use increasing rapidly.

In the 1970s, oil was the main energy resource in Turkey, with a share of about 55 per cent. Turkey started to import natural gas in 1987, and by 2008 gas had become the leading energy source, with a share of 32 per cent, followed by oil at 30 per cent and coal at 28 per cent. The share of renewable energy in the primary energy mix is about 4 per cent.

In 2008, indigenous crude oil production in Turkey was 2.2 million tonnes. In the same year, 21.7 million tonnes of crude oil were imported from the main producer countries in the Middle East, including Iran (35 per cent), Saudi Arabia (14 per cent) and Iraq (9 per cent), as well as from Russia (33 per cent) and Kazakhstan (3 per cent). Russia had the highest share of petroleum products (totally 8.9 million tonnes), at 43 per cent. Between 1987 and 1994, natural gas was imported only from the USSR. By 2008, however, indigenous natural gas production had reached 1 billion cubic metres (bcm). On top of that, a total of 37.8 bcm of natural gas was imported from Russia (62 per cent), Azerbaijan (12.3 per cent), Algeria (11.1 per cent), Iran (11.0 per cent), Nigeria (2.7 per cent) and other countries (0.9 per cent).

Turkey’s increasing dependence on energy imports is a major challenge for its foreign policy. Besides diversifying supply and energy sources, Turkey is strengthening its economic and political ties with supplier countries: Russia, Iran, Iraq, and the other countries in the Caspian region, the Middle East and North Africa. For decades, Turkey has developed projects to import gas and oil from these countries.

In the 1960s, Turkey proposed the development of an oil pipeline from Iran to the Turkish Mediterranean cost, but could not obtain the support of the Shah. The second attempt, this time with Iraq in the 1970s, was successful. The oil pipeline which runs from the Kirkuk oil fields of Northern Iraq to Ceyhan marine terminal on Turkey’s Mediterranean coast, with a capacity of 71 million tonnes per year, also supplies Turkish refineries.

|

| The construction of the BTC pipeline crowned Turkish Caspian diplomacy efforts in the late 1990s and early 2000s. |

In the 1980s, then Prime Minister Turgut Özal promoted the development of a natural gas pipeline from Qatar to Turkey and continuing to Europe. There was not much support from European countries for the expensive project, however, and Turkey’s natural gas demand forecasts did not justify the huge investment. During the same period, Turkey constructed the natural gas interconnector to the Bulgarian border. Today, the Trans-Balkan natural gas pipeline from Russia – via Ukraine, Moldova, Romania and Bulgaria – to Turkey can deliver 14 billion cubic metres per year (bcma) to the Turkish transmission system.

In 1997-2001 the Iran–Turkey natural gas interconnector was built with an initial capacity of 14 bcma. Its capacity can be extended substantially by constructing additional compressor stations. The Blue Stream natural gas pipeline, running from Russia under the Black Sea to Turkey, became operational in 2003 and has a capacity of 16 bcma.

The Turkish government is also planning to bring Egyptian natural gas to Turkey. Under discussion is the extension of the Arab pipeline which runs from El-Arish in Egypt to the Syrian city of Homs to the Turkish border and the construction of an offshore pipeline across the Mediterranean. Another important aim of Turkish external energy policy since the 1990s is to develop the gas fields of Iraq and connect them to the Turkish network. A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to prepare feasibility studies for a natural gas interconnector between Iraq and Turkey was signed in August 2007 in Ankara. Other policy initiatives to transit natural gas to the EU will be discussed below.

Turkish energy policy towards the Caspian region has often been misinterpreted by foreign policy and energy experts. In their perception, Turkey intended to obtain the lion’s share of transport profits from Caspian energy. The other argument raised against Turkey was that the country was promoting unfeasible pipeline projects by applying political pressure. In reality, the Turkish approach towards the Caspian Region and Central Asia was intended to strengthen the independence and prosperity of the newly independent states, many of which have a Turkic population. To achieve this, the Turkish government provided the countries of the Caspian region and Central Asia with technical, educational, financial and military assistance. These measures were not limited to the oil- and gas-rich countries of the region. To diversify and secure its energy supply, Turkey cooperated intensively with regional governments to create favourable framework conditions for large energy infrastructure projects and invited international companies to assess their economic feasibility. None of the large cross-border pipeline projects can be realised without the firm support of the relevant governments. Turkey did not receive any support from its European allies for its Caspian Sea policy, and cooperated with the US, instead.

|

| Azerbaijan's Shah Deniz natural gas field will be an important source for Nabucco gas. |

Turkish efforts to gain access to gas production and to explore potential gas fields in Turkmenistan have not been successful. The Trans-Caspian pipeline from Turkmenistan to Turkey could not be realised. Kazakhstan has far more potential with regard to supplying Turkey with energy, but so far Turkish companies have not managed to take advantage of it. Some observers claim that Turkey needs one or two national champions to achieve its external energy policy goals. Some observers have proposed that TPAO should again operate as a vertically integrated oil company, conducting the whole range of activities, from exploration, production, transport and refining to retail. Others want to see the public pipeline company Botaþ as a natural gas monopoly, extending its activities to the exploration and production of gas abroad.

Turkey as an energy hub

In addition to trying to enhance its energy security, Turkey has also made efforts to establish itself as an energy hub between the large oil and gas producers of the Middle East and the Caspian region and Europe. The main prerequisite for an energy hub is a good physical infrastructure. The length of the main Turkish natural gas transmission network increased from 2,000 km in 2000 to 12,300 km in 2009. The entire gas network now is 57,000 kilometres long. Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is contributing more and more to the energy security of European countries. Turkey’s first LNG facility in Marmara Ereðlisi, 90 kilometres northwest of Istanbul, has been operational since 1994. The terminal can import 6 bcma of liquefied natural gas. Turkey’s second LNG facility was built by Çolakoðlu in a location north of Izmir. The terminal has been in operation since 2006 and has a capacity of 6 bcma.

Turkey’s energy infrastructure still lacks large-scale storage capacities for natural gas. Underground natural gas storage may contribute to balance seasonal, daily and hourly changes in demand and is essential to maintain the gas flow to the consumer in the event of supply interruptions. The first underground storage facility in Turkey, with a capacity of 1.6 bcm, became operational in April 2007 in Silivri, near Istanbul. A second underground storage facility, in Tuzgölü in Central Turkey and with 1 bcm capacity, is under development.

Further conditions for a well functioning natural gas hub are a good business climate and a transparent transit regime. The Natural Gas Market Act, No. 4646 of May 2001, was an important step towards the liberalisation of the gas market in Turkey. The reduction of Botaþ’s market share in the Turkish gas trade, carried out by auctioning its gas contracts, is one of the most significant aspects of the Act. Although severely delayed, the transfer of the first 4 bcm from Botaþ contracts to private sector companies was an important step for market liberalisation. The start of the gas import and trading activities of the Çolakoðlu LNG terminal will also contribute to market development. The Turkish government should encourage trading by international gas brokers in Turkey and establish a more transparent transit regime.

Energy cooperation between Turkey and Russia

Turkey has cooperated with Russia in the field of energy for many decades. During the Cold War, many industrial facilities in Turkey – including an oil refinery and a power plant – were built with Soviet financial and technical support. In 1984, Turkey and the USSR signed the first natural gas supply agreement (for 6 bcma). Gas flow commenced in 1987, via the Trans-Balkan pipeline, through Romania and Bulgaria. Economic cooperation with the USSR was based on barter agreements and helped to increase Turkish exports – especially of traditional agricultural products – to its northern neighbour. Turkey signed a second natural gas agreement – for the supply of 8 bcma via the Trans-Balkan pipeline – with the Russian Federation in 1996. Within the framework of the Natural Gas Market Act, Botaþ transferred 4 bcma of the total 8 bcma of the second agreement to private sector companies, including Bosporus Gas, a Gazprom joint venture in Turkey.

In 1996, Russia made an offer to Turkey to supply additional natural gas via an offshore pipeline under the Black Sea. In December 1997, the Blue Stream agreement was signed between the two countries. Gas flows from Russia to Turkey via Blue Stream started in 2003. The total length of the pipeline is 1,213 km and the subsea section is 396 km long. The total cost of the Blue Stream pipeline is 3.2 billion US dollars.

A second subsea gas pipeline, parallel to Blue Stream, was first mentioned by the Russian side in 2002. In August 2005, then President Vladimir Putin officially proposed the building of the Blue Stream II gas pipeline to the Turkish Prime Minister. The Blue Stream II pipeline was intended to supply gas to Turkey and the Middle Eastern countries, including Israel. However, the main aim of Gazprom was to transit gas to Southeast Europe via Turkey. The Turkish side welcomed the offer, but gave priority to the Nabucco project from Turkey to Austria.

In response to the progress of the Nabucco project and Turkey’s reluctance to support Blue Stream II, Gazprom signed an MoU with ENI of Italy in June 2007 to implement the South Stream pipeline project. South Stream starts at Russia’s Black Sea coast, where the Blue Stream subsea section starts, and continues to Bulgaria as an offshore pipeline. Russia signed intergovernmental agreements with the transit countries Serbia, Bulgaria, Hungary, Greece and Slovenia. During Prime Minister Putin’s visit to Ankara on 6 August 2009, Turkey granted Gazprom permission to carry out the necessary geological research within the Turkish Economic Zone of the Black Sea. The capacity of the South Stream project has been increased twice by the project developers, reaching 63 bcma. The total cost of the project is now estimated at 24 billion US dollars. The length of the offshore section of the pipeline will be about 900 km. From Bulgaria, two directions for the pipeline are under investigation: one via the Eastern Balkans to Central Europe and the other via the Western Balkans to Southern Europe. However, a final investment decision on South Stream has still to be made.

Turkey is trying to involve Russia in the Samsun-Ceyhan crude oil pipeline which bypasses the congested Turkish Straits and transports Russian and Caspian oil from the Black Sea coast east of Samsun to the Mediterranean port of Ceyhan. The 550-km pipeline has a nominal design capacity of 1.5 million bpd. ENI of Italy and Çalýk Holding of Turkey are developing the project jointly. The ground-breaking ceremony was held on 24 April 2007 in Ceyhan, attended by the Italian Minister for Economic Development and the Turkish Minister for Energy and Natural Resources. The visit of Russian Prime Minister Putin to Ankara in August 2009 increased the expectation that Russian companies may join the ENI/Çalýk project. On 18 October 2009, Italy, Russia and Turkey signed an MoU on the Samsun–Ceyhan oil pipeline in Milan. On the same day, ENI/Çalýk signed an MoU with JSC Transneft and OAO Rosneft to evaluate the participation of Russian companies in the project.

|

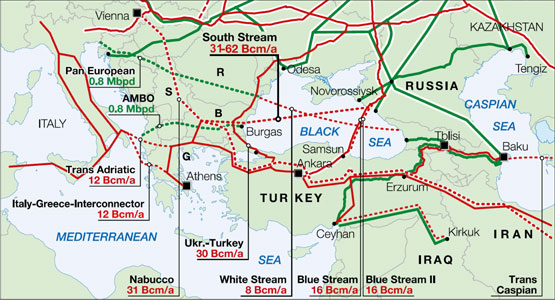

| Planned (dotted line) and existing (straight line) oil (green) and gas (red) pipelines in the Black Sea area. A lot of these pipelines cross Turkish territory or the Turkish economic zone in the Black Sea. |

Russia and Turkey also intend to jointly develop underground gas storage capacities in Turkey, according to the ‘Gas protocol’ of 6 August 2009. The ‘Petroleum Protocol’, signed the same day, foresees joint exploration and production activities by Russian and Turkish companies in third countries. On 12 December 2009, a consortium made up of Gazprom, South Korea’s KoGas, Malaysia’s Petronas and Turkey’s TPAO was awarded a contract to work in the Badra field – one of the smallest – in Eastern Iraq. Lukoil has established a petrol station chain in Turkey and is evaluating plans for further growth. Russia and Turkey are also cooperating in the field of nuclear energy. During the recent visit of Russian president Medvedev to Turkey on 11-12 May, an agreement was signed for the first Turkish nuclear power plant in Akkuyu at the Mediterranean coast to be built and operated by a consortium of Russian and Turkish companies.

Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, economic and political relations between Russia and Turkey have only intensified. Turkish construction companies, already active in Russia in the 1980s, have won contracts worth 25 billion US dollars in Russia over the past 20 years. In 2008, leaving aside trade with the EU as a whole, Russia became Turkey’s number one trading partner. The trade volume between the two countries reached 37.9 billion US dollars in 2008. Turkey is Russia’s fifth largest trading partner. Russia has a huge surplus in bilateral trade, however: in 2008, Turkey’s imports from Russia increased to 31.4 billion US dollars, the main items being natural gas, crude oil, petroleum products and coal, while Turkish exports – worth 6.5 billion US dollars – to Russia are mainly manufactured goods. According to the Turkish Trade Council in Moscow, direct investments by Turkish companies in Russia now stand at 7 billion US dollars. Close to 3 million Russian tourists visit Turkey every year. Turkey is also interested in cooperation with Russia in the defence sector. The Russian company Rosoboron won the tender to provide the Turkish army with anti-tank missiles, signing the contract in August 2008. The war between Georgia and Russia in August 2008 also put pressure on relations between Russia and Turkey. Turkey has close relations and cooperation with both countries and so found itself in a very difficult position. Ankara only mildly criticised the Russian intervention in Georgia and Moscow’s recognition of Abkhazia and Southern Ossetia as independent states. Turkey is promoting a Caucasus Stability Pact for the resolution of conflicts in the region, excluding external countries. The Georgia crisis also showed Turkey the vulnerability of the East–West Energy Corridor via Georgia.

After the end of the Cold War, many Turkish intellectuals and high-ranking military officers were discussing an alliance with Russia or a trilateral alliance between Israel, Russia and Turkey. Russia’s immense natural resources, Turkey’s rapidly growing economy, with its dynamic industry, and Israel’s high-tech know-how were seen as the potential strengths of such an alliance. Turkey’s relations with the United States cooled during the eight years of the Bush administration, mainly because of Turkey’s lack of support for the invasion of Iraq. The slow progress of EU accession negotiations and the negative attitude of France and Germany in particular towards Turkey’s membership dramatically reduced the popularity of the EU in Turkey. A strategic partnership between Russia and Turkey was suggested first during the official visit of then Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov to Turkey in 2000. The joint declaration signed during the visit to Russia of Turkish President Abdullah Gül in February 2009 was described by the Russian side as a ‘strategic document’. The official visit of Prime Minister Putin to Turkey in August 2009 elevated energy cooperation between the two countries to a strategic level. According to Sergey Markov – Director of the Institute for Political Studies in Moscow – Russia and Turkey should establish a new economic and political alliance. During the visit of President Medvedev to Turkey in May, the two countries signed 12 agreements, including the one on the nuclear power plant as well as an agreement for visa-free-travel. Russia plays an important role in the framework of Turkey’s new foreign policy, which is aimed at ensuring that there are ‘no problems with neighbours’. On the other hand, Turkey is aware of the imbalance between the two countries. Russia’s readiness to use military power to solve regional conflicts certainly does not fit into the picture of peaceful cooperation in the Caucasus and Central Asia. Future Russian interference in the internal affairs of Turkic countries in the Caucasus and Central Asia may cause Turkey to change its policy towards Russia.

Energy Cooperation between Turkey and the EU

All of this by no means implies that Turkey has not sought to establish good relations with Europe, including in the energy field – quite the contrary. Turkey is well aware that the EU is its largest trading partner by far. Roughly half of Turkey’s exports go to EU countries. EU companies have a long track record in Turkey. After the Cold War, Turkey participated in the negotiations on the Energy Charter Treaty and signed it in December 1994. During the following years, Turkey contributed to the negotiations on the Transit Protocol of the Energy Charter Treaty. Preparations for the synchronisation of the Turkish high voltage network with the European power network UCTE are at an advanced stage.

While developing the East–West energy corridor, Turkish plans included the channelling of natural gas from the Caspian region to other European countries. The Trans-Caspian pipeline from Turkmenistan to Turkey had a design capacity of 30 bcma: 14 bcma of the gas were foreseen for transit to Europe via Turkey. In 1998, Turkey signed an MoU with Bosnia-Herzegovina for future gas supply. In the same year, during the bilateral energy commission meeting with Austria, Turkey proposed to develop an infrastructure to transport Caspian gas to Central Europe. It should be noted that there was deadlock in relations with the EU after the December 1997 Luxembourg summit and no political support came from Brussels or the EU member states for the development of the East–West energy corridor.

The EU’s attitude towards Turkey started to change in 1999. In addition to the aim of rehabilitating relations with Turkey, the EU had two geopolitical reasons for this change. In 1998–99, Turkey made visible progress in negotiations on the BTC and the Trans-Caspian pipeline. The other important consideration was Russia’s reluctance to ratify the Energy Charter Treaty or to accept articles of the Transit Protocol of the Treaty that would allow the transport of Caspian energy resources to the West via the Russian transmission network. In June 1999, the European Commission invited Turkey to become a Full Beneficiary Country of the INOGATE (Interstate Oil Gas Transport to Europe) programme.

In June 2000, after a trilateral meeting in Brussels, the European Commission, Greece and Turkey signed a Concluding Statement to implement the South European Gas Ring from Turkey via Greece to Italy. In the following years, the Greek and Turkish state-owned companies Depa and Botaþ worked closely to develop a 296 km long Turkey–Greece gas interconnector. The construction work started in July 2005 and the pipeline was officially inaugurated in November 2007. The initial capacity of the pipeline – 7 bcma – may be extended in future to 11 bcma. For the extension of the network from central Greece under the Adriatic Sea to Italy a company called IGI Poseidon S.A. was established in June 2008. The Trans-Adriatic Pipeline is the other pipeline project between Greece and Italy. The 520 km long pipeline will cross northern Greece and Albania, westwards. The offshore section of the pipeline is routed from the Albanian cost through the Adriatic Sea to Italy.

At the third Austrian–Turkish Joint Energy Commission meeting in November 2001 in Vienna, the parties agreed to encourage natural gas companies from both countries to study the feasibility of natural gas transport from the Caspian region via Turkey to Austria. The meetings between OMV Erdgas and Botaþ were concluded with a cooperation protocol, signed in May 2002. In October 2002, Bulgargaz, Transgaz from Romania and MOL from Hungary joined the project. In June 2004, the Nabucco Company was established. In December 2007, RWE from Germany became the sixth shareholder of the pipeline consortium. In June 2009, an intergovernmental agreement for the realisation of the Nabucco project was signed. The 3,300 km long pipeline will cost 7.9 billion euros and has a design capacity of 31 bcma. The Nabucco Company will make the final investment decision on the project in the last quarter of 2010.

Both of the abovementioned projects enjoyed the financial support of the EU’s Trans-European Energy Networks programme for their economic and technical studies. However, the EU was criticised in Turkey for the slow pace of the development, the lack of coordination between the projects and the contradictory decisions and policies of member states. All competing pipeline projects supported by an application from a member state to Brussels are on the EU’s priority list. There is no ranking of the projects based on their contribution to Europe’s energy security.

|

| Silvio Berlusconi of Italy, left, Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey, centre, and Vladimir Putin of Russia join hands after a signing ceremony on South Stream in Ankara, July 2009. |

There are a number of critical questions that can be asked about the European Commission’s negotiating position on the Southern corridor with Turkey. The EU emphasises the need for further reforms in the Turkish natural gas market, but has not yet opened the Energy chapter in the accession negotiations. The Turkish demand to channel 15 per cent of the natural gas from transit projects to domestic supply is perceived as unacceptable, but the EU should pay more attention to the energy security of a future member. Between 2004 and 2009, valuable time was lost in securing the necessary volumes for the pipeline projects of the Southern corridor. Turkmenistan signed new supply agreements with Russia and China; Azerbaijan signed an agreement with Russia.

The recent activities of the Nabucco partner companies towards securing concessions in the region are a step in the right direction. However, a natural gas purchase agreement with the Shah Deniz consortium in Azerbaijan has not yet been signed, although it is essential for the investment decision with regard to the initial phase of the Southern corridor. There are problems regarding the other potential suppliers eligible for the second phase of the project. Iran, with the second largest gas reserves in the world, is not yet ready to resolve its nuclear dispute with the US and Europe peacefully. The other potential gas supplier, Turkmenistan, needs new investments to increase gas production. The Arab pipeline carrying Egyptian gas may be extended to Turkey in a short time, but the pipeline capacity and the increasing demand in transit countries Jordan and Syria will limit the volumes available at the Turkish border. Iraq is on the way to becoming an important gas supplier for Turkey and the Southern Corridor. Foreign consortiums participating in the oil field auctions of the Iraqi government are hopeful of supplying at least the second phase of the Nabucco project. As already described, there is a huge gas supply potential in the region, but gas sales agreements are necessary to trigger investment. The development of the Southern Corridor will put the EU’s external energy policy to the test. If the Southern Corridor fails to materialise, it will harm the credibility of the EU in the region and put pressure on EU–Turkey relations.

EU Membership

A final word should be said on the issue of Turkey’s prospective EU membership. In December 1964, Turkey became an associate member of the EEC, with the prospect of full membership. After 40 years, at the December 2004 summit, the EU declared that Turkey had fulfilled the Copenhagen Political Criteria to a considerable extent and that accession negotiations should be started. During the following years, relations between the EU and Turkey again changed for the worse after repeated statements from Berlin and Paris about a ‘privileged partnership’ instead of full membership and Turkey’s reluctance to extend the Association Agreement with the EU to the Greek part of Cyprus until the isolation of the Turkish part of the island is lifted.

Turkey will play a crucial role in future energy supplies to Europe. Turkey has close ties with the countries of the Caspian Region and the Middle East and a well developed energy infrastructure. The EU should encourage Turkey to speed up the accession negotiations and to become a member of the community in the near future. However, the support of the Turkish public for EU membership has fallen dramatically in recent years. It is not impossible that the next generation in Turkey might not even want to join the EU, even if all the criteria have been fulfilled. Many observers in Europe understand the importance of Turkey’s membership for the future of the EU. The EU needs Turkey not only for its energy security, but also for the contribution it would make to the European economy, the European defence system, European neighbourhood policy (Caucasus, Central Asia and the Middle East) and the dialogue with the Islamic world. With a strong political will on both sides and a fixed date for Turkey’s membership, Turkey may yet become a member of the EU within a few years. If this does not happen, the EU’s policy of energy diversification will suffer a serious blow.

|

Dr Yurdakul Yiðitgüden served as Under-Secretary of the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources from 1997 to 2003. He successfully led the Caspian Energy Policy of Turkey and coordinated the progress of the East–West–Energy Corridor and the South-European Gas Ring with regional governments and other global players and took a leadership role to implement energy market reforms. This article is based on a presentation Yurdakul Yiğitgüden gave at an international expert meeting on energy relations between the EU, Turkey and Russia, which was jointly organized by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) and the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP) in Berlin in December 2009. For more background information on the energy relations between EU, Turkey and Russia, click here |

Discussion (0 comments)