Gambling on Greenland

on

Gambling on Greenland

For the first time in its history, Greenland has awarded offshore oil and gas exploration licenses to oil companies, opening up this Arctic frontier to future oil and gas production. The licensing awards followed the first ever oil and gas discoveries in Greenland, made in August by Cairn Energy, propelling this nation with a population of 56,000 into the limelight of the global energy market. The government welcomed the discoveries, but Greenpeace has embarked upon an aggressive campaign to stop any more exploration in the area dubbed Iceberg Alley.

|

| The Arctic region: the next energy frontier |

What has drawn these operators to this Arctic island where ice layers up to 3,000m thick cover over 80% of the land? Exploration is a gamble involving hundreds of millions of dollars. Initial investments on the exploration blocks are expected to be between 1 and 1.5 billion Danish kroner (€130-200 million) per block. But the oil companies have no choice. They need to add new oil and gas reserves to their portfolio to keep up their production as their existing assets mature and output declines. Moreover, many of the easily accessible reserves in the world, for instance in the OPEC countries and in Russia, are off-limits to the western oil majors, so they are forced to look to frontier areas. As Statoil’s senior vice president for global exploration Tim Dodson put it: ‘While early access to such frontier opportunities entails more uncertainties related to probability of discovery, the potential reward of one or more sizeable discoveries may be high.’

First ever

All of the winners of the Greenland blocks have committed to drilling 2 to 3 exploration wells. Whether these efforts will pay off is uncertain. Until a commercial discovery is made no one will know how challenging and costly oil production in the Arctic will be. Oil production on the Arctic shelf is estimated

| Until a commercial discovery is made no one will know how challenging and costly oil production in the Arctic will be |

Oil exploration in Greenland goes back to the 1970s, but did not yield any results until the past summer, when the independent Scottish oil company Cairn Energy for the first time discovered hydrocarbons. The company, which is headquartered in Edinburgh, has interests in eight offshore areas spanning 72,000 square kilometres and has budgeted $1 billion for its ten well drilling campaign over the next three years. It views Greenland as a key growth area.

From July to October, Cairn Energy drilled three wells on its Sigguk block, off northwest Greenland near Canadian waters. After reaching 4,358 metres in volcanic sections on Sigguk, the company found two types of oil within its Alpha-1S1 well. They have different origins and levels of maturity, but a company spokeswoman declined to reveal more details for commercial reasons. Cairn is carrying out further geochemical analysis to develop a better understanding of its samples. The company had to suspend drilling at the onset of the winter. Ove Karl Berthelsen, Greenland’s Minister for Industry and Mineral Resources, described the oil discovery as an ‘encouraging result’.

Despite gas showing within Cairn’s two other wells on Sigguk block, these were abandoned because the gas discoveries were not large enough to justify development. The two wells cost $185 million to drill and when Cairn Energy released this update on October 26, its shares slumped by 7%.

When the weather allows, Cairn will drill a fourth well on Sigguk block, in 300-500 metres of water. These wells are the first to be ever drilled in this area. The company is using two state-of-the-art drilling vessels – the Stena Forth, a drillship, and the Stena Don, a semi-submersible drilling rig, which can

| Oil production on the Arctic shelf is estimated to cost between $500-700 per ton compared with developed regions where the costs are as little as $30-40 per ton |

Other operators in Greenland are still interpreting their seismic data to spot potential drilling locations. A spokesman of Danish company Dong Energy told European Energy Review that it could start drilling in 2011/12. ‘We are still deciding whether to do more seismic or not having collected some in 2008.’ In June, PA Resources started 6,300 km of 2D seismic drilling on Block 8 in west Greenland – a high-risk, high potential exploration frontier. ExxonMobil and Chevron also have interests off Greenland, but Chevron doesn’t plan to start exploration until 2014.

Debatable

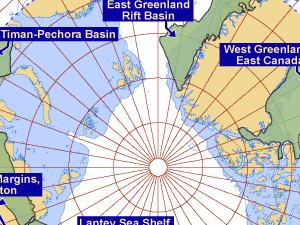

So how much oil and gas is there to be found in the Arctic waters off Greenland? According to research by the US Geological Survey (USGS), undiscovered offshore oil and gas resources north of the Arctic Circle between west Greenland and eastern Canada, including Baffin Bay, are more than 18 billion barrels of oil equivalent (boe). This is comparable to the total remaining oil and gas reserves in the UK part of the North Sea, which still contains 15-25 boe of recoverable reserves. The world currently consumes about 29 billion barrels of oil each year.

|

| Location of Arctic Basins assessed by the USGS (click to enlarge) |

Greenpeace launched a high-profile campaign in August, directed against Cairn’s drilling operations. Four activists scaled Cairn’s rig, forcing the company to suspend drilling for 30 hours. The activists gave up when the weather deteriorated and were subsequently arrested by the Greenlandic police. Sim McKenna, one of the campaigners who hung fifteen metres above the bitterly cold Arctic Ocean, said the action was necessary as the ‘drilling rig we're hanging off could spark an Arctic oil rush, one that would pose a huge threat to the climate and put this fragile environment at risk.’

Baffin Bay is home to 80-90% of the world’s Narwhals, and to blue whales, polar bears, seals, sharks, cormorants, kittiwakes and numerous other migratory birds. Greenpeace is calling for a moratorium on all new deep water drilling operations, in light of the Deepwater Horizon disaster. ‘Pressing on with new wells is reckless and irrational in the extreme,’ says Ayliffe. ‘Cairn Energy has steadfastly refused to publish the plan it has for dealing with an oil spill in the region, whilst the Greenlandic government has turned down Freedom Of Information requests to release the same documents. Because of this we have no idea what is being done to reduce the risk of a spill, which is incredible when you consider the risks oil companies have to take to operate there.’

Safety rules

It is not only environmentalists who are concerned about whether operators are equipped to contain spills in the Arctic. The issue is intergovernmental. Canada, which shares waters with Greenland, sent officials there to monitor and inspect Cairn’s drilling operations. ‘Following the incident in the Gulf of

| Even if we managed to pump out all the oil from under the entire Arctic, it would only provide enough to meet the planet’s demand for a couple of years |

The European Commission says that responsibility for the safety of oil operations rests with Greenland. ‘As with any oil exploration, spill or environmental damage cannot be ruled out, but the risks are kept to as low as possible with the existing legislation and its supervision’, says a spokeswoman from the Commission. ‘The correct implementation of the safety rules by exploration companies is the responsibility of the authorities in Greenland.’

Greenland is in some ways a peculiar nation. Geographically it is part of the North American continent. Geopolitically, the country is part of Europe. Nationally Greenland is part of Denmark, as a self-governing colony following 300 years of Danish rule. The government of Greenland encourages oil development because it is keen to find another source of income outside fishing and to reduce its reliance on £500 million per year in subsidies from Denmark. A full-fledged oil industry could lead to full independence from Denmark, offering jobs and upskilling the local population.

Berthelsen, the Minister for Industry and Mineral Resources, is ‘very confident that the licence holders will help explore Greenland’s oil potential in a safe and appropriate manner’, he says. ‘Safety has top priority and I shall be looking forward to following the results of their work.’ The government has scrutinized companies’ emergency response procedures and safety, health and environmental profiles,

| From the west coast of Greenland to east Canada there looks like there could be possible significant oil accumulations |

Common approach

Despite the high costs, the high risks, the stringent safety requirements and the opposition from environmentalists, oil companies seem to be determined to push on with oil and gas exploration in Greenland’s waters. Last November, the companies got together to form the Greenland Oil Industry Association (GOIA), which is chaired by Arne Rosenkrands of Dong Energy. GOIA will share data, best practices, and resources and liaise with the local government on environmental and safety matters. ‘With the increased focus on Greenland as a potential oil and gas province, the energy companies present in Greenland have been in dialogue on the need for a common approach to several issues. We are confident that the GOIA will make a solid contribution to the successful development of the industry in Greenland’, Rosenkrands says.

|

| Icy Greenland |

Clearly for the oil industry the stakes are high, and the outcome of their frontier battle against ice and environmentalists, is uncertain. But the potential rewards are also considerable. Says research geologist Donald Gautier at the USGS: ‘The geology of Northeast Greenland is very interesting, but the problem is that it is choked with ice all year long. In extreme north Greenland in the Lincoln Sea basin there could be hydrocarbon resources but it is so remote and again there are the ice issues. From the west coast of Greenland to east Canada there looks like there could be possible significant oil accumulations.’

Discussion (0 comments)