Gas is dead. Long live gas!

on

Why policy failures are opening up gas opportunities in Europe

Gas is dead. Long live gas!

Europe's natural gas industry is going through dark times. Policy failures within the European Union have combined with unexpected developments elsewhere to create a business environment hostile to gas. Amidst all the gloom, however, there are glimmers of light. Sooner or later Europe's policy-makers will have to wake up to some inconvenient truths: that gas is being elbowed out of the energy mix by coal and subsidised renewables; that greenhouse gas emissions are falling much more slowly than expected, largely because of the failure of carbon-pricing policy; that the US now has a competitive advantage over Europe because of its cheap energy; and that political opposition to shale gas in Europe is preventing some countries from exploiting their own unconventional resources. Sooner or later the EU will need to re-think energy and climate policy – as the UK is currently doing.

|

| (c) Spencer Platt / Getty Images |

The challenges facing the natural gas industry in Europe have been widely documented – not least in articles that have appeared in European Energy Review. Europe's gas businesses have gone through considerable structural change over the past decade as regulatory pressures have grown, mainly because of the determination of policy-makers to create a single competitive internal market. Contractual tensions have led to large financial losses amongst companies forced to buy imported gas under oil-indexed long-term contracts and to sell it on at lower hub-based prices.

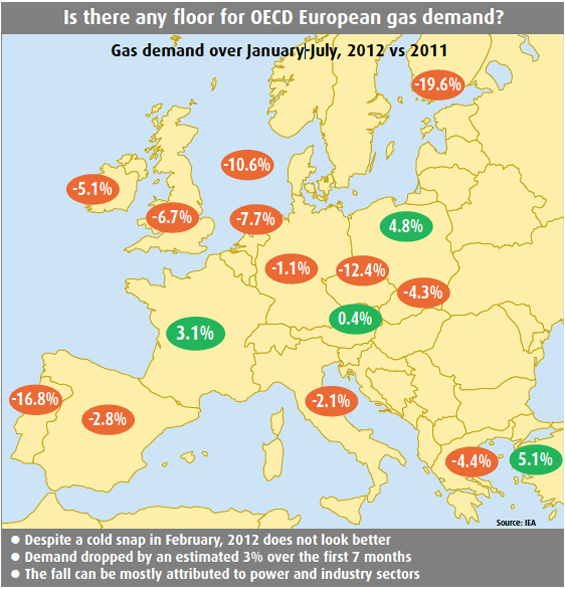

What was abundantly clear in Vienna, however, is that the main preoccupation of the industry today is an apparently structural loss of demand for its product. Taking their toll are heavily subsidised renewable energy sources, imports of cheap coal displaced by shale gas in North America, energy efficiency measures, and the economic woes of the Eurozone – all compounded by the failure of carbon-pricing policy. Gas demand in the European Union fell by 10% between 2010 and 2011, and a further fall is expected this year. The map below – from a presentation in Vienna by Anne-Sophie Corbeau, Senior Gas Analyst at the International Energy Agency (IEA) – illustrates this all too clearly.

Missing out on a "Golden Age"?

In the first seven months of 2012 overall demand was down by an estimated 3%. I asked Corbeau where Europe stood in the much-vaunted "Golden Age of Gas" that the IEA foresees. "Everywhere except in Europe," she replied.

As part of the electronic polling at the Vienna EAGC, Gas Strategies asked delegates: "What is likely to be the biggest demand driver between now and 2020?" Only 12% thought that "demand for gas will grow robustly as renewables fail to live up to their promise and nuclear power wanes in the wake of Fukushima". Last year almost half the voters chose this option. All the other possible responses were for a fall in demand for various reasons – so almost 9 out of 10 delegates felt that demand would decline over the coming decade.

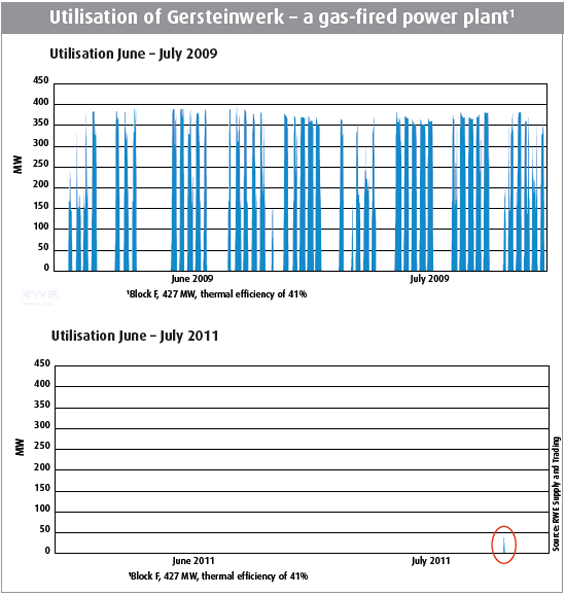

The scale of recent gas demand loss was dramatically illustrated by Stefan Judisch, CEO of RWE Supply & Trading, with the charts below. They compare the utilisation of a German peak-load gas-fired power station in June-July 2009 and June-July 2011.

"No," said Judisch, to ironic laughter from the floor, "the second chart is not a mistake. This is funny – and you laughed about it – but the economic reality behind it is tremendous."

Electric shock

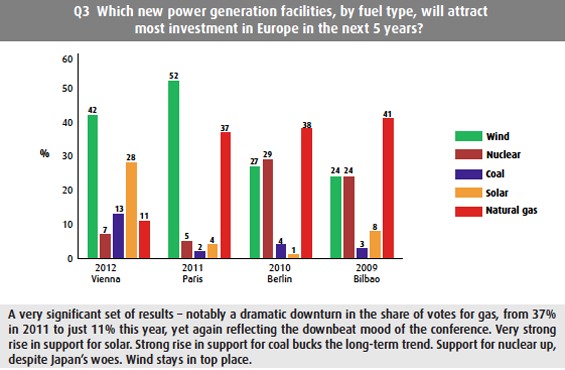

Given the importance of electricity generation in driving gas demand, delegates were asked: "Which new power generation facilities, by fuel type, will attract most investment in Europe over the next 5 years?"

The results, in the chart below, are shocking. Support for gas was down to 11%. In 2009 and 2010, gas was in the top spot (having been there since EAGC polling began in 2005). It was overtaken last year by wind, with 52%. Wind was top again this year but down to 42%. The biggest gain was for solar, which went from 4% to 28%. Coal jumped from 2% to 13%, a larger share than natural gas for the first time.

Commenting on how Europe's power generation fuel mix is changing, BG Group's Chris Finlayson – who will replace Frank Chapman as CEO from the start of 2013 – told delegates: "In Germany there are 11 GW of new coal-fired power stations under construction . . . If you look across the North Sea to the UK, a similar picture: coal consumption is on the up; nearly 5 GW of gas plant has been mothballed over the last 18 months. The only difference is that there is no new coal-fired capacity under construction in the UK."

The resurgence of coal in Europe has been driven by the price differential with gas, which in turn is being driven by several factors. One is the impact of the unconventional gas revolution in North America on coal prices. Cheap US gas has encouraged electricity generators there to switch from coal, leading to cheap US coal finding its way into Europe. Between 2010 and 2011, coal consumption in Europe grew by 4%, from 276 Mtoe to 286 Mtoe.

Another factor is that much of the gas that comes into Europe under long-term contracts is still priced on the basis of indexation to oil or oil products, making it relatively expensive. At the same time, heavily subsidised renewable energy sources – wind and solar power – have been growing rapidly as a result of policies to mitigate climate change. Meanwhile, the one policy instrument that could have made a difference amidst all this complexity – the EU's Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) – has so far spectacularly failed to deliver rational carbon prices.

Inconvenient truths

So where does this leave European energy and climate policy? Sooner or later, Europe's policy-makers will have to wake up to a number of inconvenient truths. Europe's future energy mix appears to be on a trajectory that makes no sense in a carbon-constrained world, largely because of the failure of carbon-pricing policy. A mix of "unabated gas" (gas without CCS) and renewables makes much more sense, in terms of climate change mitigation, than a mix of unabated coal and renewables.

This is shown by the embarrassing fact that greenhouse gas emissions in the US are falling sharply whereas emissions in Europe are falling more slowly than anticipated, and could start rising, because cheap shale gas in the US is driving cheap coal across the Atlantic into Europe. Moreover, the shale gas boom in the US is leading to low-cost energy, particularly electricity, which in turn is leading to an industrial renaissance by giving US industry a competitive edge over industries in Europe (and Japan). European companies have already begun complaining; Japan's have been complaining for some time.

In a scathing commentary on how Europe's governments are impacting the gas business, Erwin van Bruysel, Executive Vice President for Long Term Gas Supply at Eni's Gas & Power Division, told delegates: "Europe seems to undergo what happens across the oceans without having any significant impact itself. We accelerate closure of our nuclear plants in the aftermath of Fukushima, not to produce more power with natural gas but with imported American steam coal that has lost its home market to shale gas. The golden age of gas in the European power market has lost its shining growth potential under a thick layer of American coal dust."

Grounds for optimism

Paradoxically, it is precisely this predicament that policymakers have created that should give the European gas business some grounds for optimism. The industry appears to be all too readily accepting current market conditions as a 'new reality' that cannot be changed. This kind of fatalism is unnecessary and could even be dangerous.

The fact is that policies cannot continue as they are. To believe that Europe is headed for an energy future dominated by renewables and cheap coal generation is to believe that Europe will be fundamentally cut off from the rest of the world, where abundant gas is driving economic growth and reducing CO2 emissions. This would lead to a European energy sector dominated by subsidy, managed markets and high-cost generation versus a more competitive gas-based energy sector elsewhere. A truly unsustainable future.

So let us take a look at some of the more convenient (for the gas business) truths.

There is no doubt that the fundamentals of chemistry and physics work in favour of gas. As the most hydrogen-rich of the fossil fuels, natural gas emits much less carbon dioxide per unit of energy generated than coal or oil because the hydrogen in methane combines with oxygen to form harmless water vapour.

Moreover, modern gas-fired combined-cycle gas turbine (CCGT) power stations have efficiencies approaching 60%, significantly higher than even the best modern coal-fired plant. Gas-fired power stations are also good at load-following and so make an ideal complement to back up intermittent renewables.

As to pricing, it seems clear that oil indexation is no longer rational in liberalising gas markets and that its prevalence will continue to wane. That should help to make gas more competitive.

Currently coal prices are low compared with 2011 but higher than they were in 2010. US shale gas is undoubtedly abundant, but with new gas-based industries seeking to set up business there, new LNG export projects seeking approvals, and rising demand for gas in the power sector, can we be sure that Henry Hub prices will remain low on a sustained basis?

Likewise in Europe CO2 prices have been low but the next phase of the ETS scheme, due to start next year, may bring about a change in the carbon price. Simply put. Policymakers cannot let the ETS continue as it is. They will have to "fix" it or substitute it with another policy that does work.

A new dawn for gas in the UK

Interestingly, in the five weeks since the Vienna EAGC, the government of Europe's largest gas-consuming country, the United Kingdom, has issued proposed new policies that aim to address all of these trends – more of a new dawn for gas in the UK than just a few glimmers of light:

* On 29th November the energy and climate secretary Ed Davey introduced to parliament a new Energy Bill, the centrepiece of which is radical reform of the electricity market aimed at attracting investment in a "diverse low-carbon energy mix . . . of renewables, new nuclear, gas and CCS". Particularly relevant to gas is a proposed capacity market which would go some way towards remunerating operators of gas-fired power plant for their role in providing backup for intermittent renewables. The bill is expected to receive royal assent in 2013.

* On 5th December the government published a new Gas Generation Strategy, a package of "measures to provide market certainty for gas investors and to ensure fair competition". Interestingly, it was announced by the Chancellor of the Exchequer (finance minister) George Osborne during his Autumn Statement on the country's finances, highlighting the more prominent role that – in his view – gas should be playing play in the UK economy. The strategy addresses a wide range of gas-related issues, including the profitability of gas generation investment, the security and affordability of gas supply, the development of shale gas resources and the promotion of CCS technology.

* On 13th December the government announced it was lifting an 18-month moratorium on fracking, a controversial technique used to extract natural gas from shale; it was imposed following tremors resulting from its use in Lancashire by a company called Cuadrilla.

|

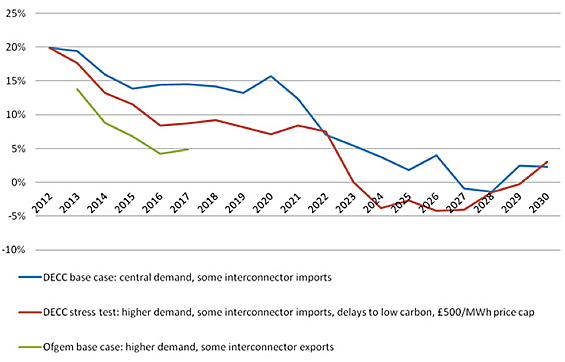

| This chart from the UK government's Gas Generation Strategy report shows how electricity generation capacity margins are projected to evolve in the absence of new investment in generation capacity. The report says: "New gas plant will play an important role in helping to replace those plants that retire and, increasingly, in helping to balance the intermittency and inflexibility of other forms of generation coming online." |

Whether the various policies proposed by the UK government will actually achieve their objectives will continue to be fiercely debated over coming months. That said, the aspirations are laudable and go a long way towards acknowledging the crucial role that natural gas will need to play in the UK's energy mix and the obstacles currently in the path of potential investors in new gas-fired power stations.

If other EU countries follow, the future for gas in Europe might be brighter than many in the gas industry now think.

|

An integrated European gas market: how realistic is it? One of the key conclusions to emerge from the discussion and debate at the Vienna EAGC was that the process of creating a single gas market in the European Union has gained considerable momentum. The deadlines may look challenging, and the various stakeholders have their own particular dissatisfactions with the process, but progress is undoubtedly being made. Commenting on how regulation is affecting gas market development in Europe, Kevin Alger, Head of Trading at RWE Supply & Trading, said: "In some markets – namely the UK, the Netherlands and Germany – liquidity continues to increase, price discovery is more transparent, and bid offers are tighter than ever. However, it's far from universal. In other countries markets have not developed at the same pace – in my view because regulators refuse to learn the lessons of those countries that have already implemented fully functioning markets. They should concentrate their efforts on harmonising rules through the implementation of network codes, as defined in the Third Package, first. We should also avoid wasting time on market coupling initiatives and concentrate instead on capacity allocation and congestion management issues ." He added that "Broadly speaking, the network codes and guidelines developed to date around capacity allocation and congestion management and balancing are progressing well. The danger is that regulators, the [European] Commission and politicians decide that things aren't happening quickly enough and disrupt the process through more initiatives." A key element of implementation of the Third Package is the Gas Target Model proposed by the Council of European Energy Regulators (CEER). It envisages the creation of functioning, physically connected, wholesale markets structured as entry-exit zones to facilitate the development of liquid and transparent virtual trading hubs across Europe. Gas Strategies asked delegates: "How realistic is this vision?" Almost half opted for: "It all sounds good in theory, but practical implementation will be hampered by the differences between national markets." Only 1% opted for: "The proposals are well thought through – and the deadlines realistic." A third thought that while the proposals were well thought through, the deadlines were not. A fifth opted for: "Sooner or later, Europe's regulators and policy-makers will wake up to the fact that a single integrated competitive internal European gas market is an impossible dream." In other words, most of those voting were more concerned about how long it might take to implement the proposals than their viability. That said, the fact that as many as 1 in 5 voted that a single internal market remains an "impossible dream" should concern regulators. Delegates gave a muted thumbs-up to the economic justification for investment in new interconnection capacity between markets. Gas Strategies posed the question: "A crucial part of the Gas Target Model is that markets within Europe need to be physically interconnected to achieve market integration and enhance security of supply. Will the building of the necessary new interconnection capacity be economically justified?" A majority of voters, 55%, believed that it would, either because capacity would only be constructed if enough demand existed to justify its cost, or because the benefits from improved supply security would enable regulators to spread costs across all gas consumers. However 29% thought it would burden consumers with unnecessary costs while 16% opted for "the idea may look attractive to theoretical economists but it is not what Europe needs". We did not get to hear the regulators' views in Vienna because they were largely absent. |

|

Report on European gas market from Gas Strategies To download the report: European gas - shaping strategies for survival, from Gas Strategies Consulting, click here. |

Discussion (0 comments)