German shale gas faces uphill battle

on

German shale gas faces uphill battle

Major oil companies are exploring tight and shale gas reservoirs in Germany, hoping to be able to reproduce the American unconventional gas revolution. German resources, experts say, could be large enough to change the energy equation in Germany significantly. Europe's largest economy is a major importer of gas and oil. But there is still uncertainty about the size of recoverable reserves. Worse, public opposition to shale gas production is growing, making it not unlikely that the German gas boom will go bust before it has started.

|

| Workers fracking natural gas (photo: PSFK) |

It's an oversimplified analogy, but that's pretty much what's happening right now in Germany.

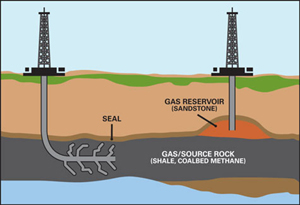

In Lower Saxony, North Rhine-Westphalia and Saxony-Anhalt, international oil companies, mainly from North America, are re-evaluating so-called unconventional gas fields - hydrocarbons trapped inside geological formations such as tight sandstones, shales or coal. The companies get the gas out by drilling into the rocks horizontally and then cracking them with a high-pressure missile of water mixed with sand and chemicals. The technology is called 'hydraulic fracturing', or 'fracking'.

In the United States, as most of our readers will know, fracking has unleashed a shale gas revolution, doubling domestic reserves. North American companies as a consequence scrapped plans to import LNG from the Middle East, with the tankers reserved for North America selling their load in Europe and Asia. This has kept spot prices low and has made the effects of the US shale gas boom global.

With the market maturing in North America, companies are looking for new shale gas opportunities. At the moment, they have every reason to do so. Oil prices hover around $120 a barrel, making gas an attractive alternative; ageing coal and nuclear power plants have been or will be shut down, making new gas-fired power stations the preferred choice for power producers; and finally, gas, experts predict, will play a more important role as a back-up to the fluctuating renewables. The oil and gas companies have now set their eyes on Europe for new unconventional gas reserves, and on Germany in particular.

In several states, companies are snapping up exploration permits for promising lots in a rush-to-resource frenzy, experts say.

'Exploration permits covering nearly two thirds of the state of Lower Saxony have already been given out,' Klaus Söntgerath, an expert with the Lower Saxony State Mining Authority, or LBEG, tells European Energy Review.

Pipeline projects

The companies planning to drill for unconventional gas (shale gas, tight gas and coal bed methane) in Germany include supermajor ExxonMobil, BASF's oil and gas arm Wintershall, 'Realm Energy, a company specializing purely in shale gas exploration. The firm most active in Germany is ExxonMobil. It

| In North Rhine-Westphalia, ExxonMobil plans to invest at least $100 million in unconventional gas drilling |

If the companies are successful, they could change the energy market in Europe's largest economy.

Germany imports about 66 billion cubic metres (bcm) of the 78 bcm of gas it uses annually (according to 2009 figures from the BP Statistical Review). Russia accounts for more than 40 percent of those imports. If Germany’s shale gas reserves prove economically recoverable, Gazprom would have to make more efforts to offer competitive contracts, especially as spot prices remain low. And a German shale gas boom would also affect the business cases for expensive pipeline projects such as Nabucco or South Stream.

But the 'if' at the start of the previous paragraph is a pretty big one. There are several hurdles that could stop a shale gas boom in Germany before it really begins.

The first hurdle is actual reserves. Many different figures are floating around how big Germany's - or Europe's - unconventional gas potential really is.

|

| Unconventional (left) vs. conventional (right) gas production (illustration: DTE Energy) |

Consultants WoodMackenzie estimate Europe’s shale gas reserves potential at an even more modest 4000 bcm. They foresee 13 bcm worth of yearly shale gas production in Europe in 2030 (that translates into be 45 rigs drilling around 400 wells) under a base-case scenario. Their more optimistic scenario foresees 60 bcm of yearly production (170 rigs, 2,000 wells). (Norway’s current annual gas production is around 100 bcm.)

‘In any case, it’s 15 years at the minimum before we will start to see a significant amount of production’, Ben Hollings, the head of WoodMackenzie’s gas research division, said last month at the Gastech conference in Amsterdam.

Worrisome reports

Even the industry warns of all-too-optimistic forecasts. ‘It’s practically impossible to come up with a meaningful figure for the gas resource in the shales’, Simon Blakey, an expert with Eurogas, the European gas industry association, said at Gastech. ‘You don’t know how productive the shale is going to be after you drill well after well after well.’

And that’s probably where the biggest hurdle for the shale gas boom comes in – public opposition to well-drilling.

In the United States, the shale gas boom was helped by the fact that landowners also own the resources beneath the surface of their land. In Germany, those resources belong to the state. The story of American pensioners becoming rich thanks to shale gas exploration on their land won’t be repeated here.

Moreover, worrisome environmental reports have emerged from the United States, where companies hunting for shale gas have drilled hundreds of thousands of wells over the past years. US scientists

| 'The political and public discussion is putting the brake on activities' |

Schönes Lünne

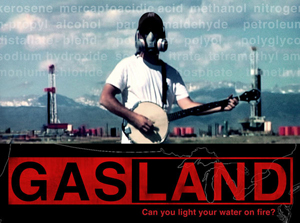

The controversial and much-contested documentary Gasland, nominated for an Academy Award, has moved those concerns into a worldwide spotlight. That wasn't a major problem in the US, where the film was released in 2010 - because the wells had already been drilled.

|

| The much-contested documentary 'Gasland' was nominated for an Academy Award |

Perhaps the company is too busy dealing with citizen movements such as 'Schönes Lünne' ('Beautiful Lünne'), an advocacy group that aims to prevent shale gas drilling near this small town in Lower Saxony. In neighbouring North Rhine-Westphalia, the state government, under pressure from local politicians, late last month imposed a moratorium on new shale gas drilling. ExxonMobil has tried to engage local advocacy groups via open roundtable discussions that started last week in Osnabrück. It's not expected to silence the opposition anytime soon.

A trip to Texas

‘The political and public discussion is putting the brake on activities’, Söntgerath, of the LBEG, tells EER. ‘Companies are engaging the public right now, and they’re carefully observing the negative publicity.’

Unlike the public, Söntgerath isn’t worried about the environmental effects of shale gas exploration. ‘Companies have been fracking here since 1977,’ he says. In 2008, ExxonMobil conducted a shale gas frack at Damme in Lower Saxony, ‘the only one we’ve had in Germany.’ The frack was conducted at a depth of 1,100 meters and cracked the rock horizontally for about 160 meters. ‘Everything went as planned.’

At Damme, the groundwater table sits at a depth of 30-40 meters, Söntgerath says. ‘So between the frack and the groundwater lie several hundred meters of rock and clay,’ he says. ‘It’s virtually impossible that frack fluids make their way into the groundwater via the geological formation.’

Söntgerath just came back from a trip to Texas where he talked to local officials to learn from what has happened there. The problems that have cropped up in the US are due not to fracking, but to poor

| The gas industry knows that it will have to do things differently in Europe |

Either way, the gas industry knows that it will have to do things differently in Europe. Planning restrictions are often tight, in part because of more stringent environmental laws and because of the continent’s dense population structure. Up to 400 people live on each square kilometre in EU countries, compared with 80 in the US.

'We can't drill the number of wells we've been drilling in the US,' Doug Bentley, the shale gas manager for Europe at Schlumberger, the world's largest oil and gas field services company, said at Gastech. 'They have to be placed better, we have to limit the number. We have to do more with less.'

So what if Germany, or even the whole of Europe, turns out to be too hostile to shale gas exploration? The oil companies will simply move somewhere else, says Blakey from Eurogas. 'They will look to Indonesia, or China or Australia.'

|

World shale gas resources according to the Energy Information Administration The US Energy Information Administration's 'World Shale Gas Resources: An Initial Assessment of 14 Regions Outside the United States' offers interesting figures. For instance this table, which shows the estimated shale gas technically recoverable resources for select basins in 32 countries, |

Discussion (0 comments)