Ghana: a race against the oil curse

on

Ghana: a race against the oil curse

The West African state of Ghana has the potential to become a major oil producer. Its oil reserves are significantly bigger than initially estimated. But then so is the challenge posed by the management of such riches. The Ghanaian government is becoming increasingly assertive, with Members of Parliament being trained in the niceties of oil contracts and royalty arrangements. ‘In the past Ghana uncritically signed agreements with the oil companies. Those days are over.’

|

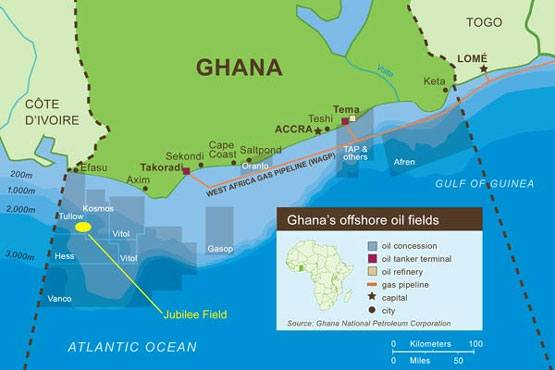

| Oil production off the coast of Ghana |

Takoradi lies some 250 kilometres west of the Ghanaian capital of Accra. Situated a further 250 kilometres west is Abidjan, capital of the Ivory Coast. Not so long ago Takoradi was a port city in decline, welcoming a mere two vessels a month to its dilapidated harbour. But since oil was discovered, times have changed dramatically. The discovery of the Jubilee oilfield in 2007 has dynamised the local economy. Oil corporations and service companies have engendered a huge demand for plant and personnel. The market value of the rundown colonial mansions along Beach Road has exploded and there’s a running battle for commercial sites.

The further development of the oilfield and the increasing number of exploration companies searching for other fields out to sea has led to a rapidly growing offshore industry. Two oil rigs, supply vessels and a growing number of geological research vessels all require operational support. Shipping agent Speijer manages the customs clearance of building materials, ship supplies and crew transfers, including helicopters and aircraft. Not exactly the standard package offered by a shipping agent. ‘The oil find has resulted in a new economy, and then you can’t simply keep doing what you’ve always done,’ Speijer explains. ‘We’re trying to get a piece of the action.’

Jubilee

For years Ghana was ignored by most oil companies. That didn’t stop the country from scouting for oil and investors – albeit with little success at first. So no one in the oil sector lost any sleep over the cheap offshore concessions granted by Ghana in 2004 to Kosmos Energy of the US and Anglo-Irish Tullow Oil. But that all changed in 2007, when they announced spectacular finds which sent a shockwave through the industry. Both companies discovered large reserves of ‘light’ – high-grade – oil. After further drilling, in late 2008 the capacity of the new Jubilee field was estimated at more than 1.2 billion barrels of oil – a considerable fortune with oil prices of some $80 per barrel. Not only that, but the field also holds large reserves of gas amounting to some 800 billion cubic feet (bcf) – equal to the annual consumption of Australia. Jubilee was the biggest offshore oilfield discovered off the West African coast for years and Kosmos and Tullow shares rocketed.

Production from the Jubilee field, which is coming on line in October this year, is estimated at 120,000 barrels per day (bpd), later ramping up to 240,000. Those are relatively modest numbers, but new finds off the coast of Ghana and beyond suggest that Jubilee could form part of an extended chain of oilfields stretching northwards to Sierra Leone and Senegal. The biggest oil multinationals, including ExxonMobil, BP and China’s CNOOC, are now all too eager to come on board. According to Ghana’s Ministry of Energy, future oil production is set to outstrip all current projections. ‘We believe that Ghana will be producing a million barrels per day in five to six years,’ says Kwaku Boateng, the Ministry’s Director of Petroleum Upstream. ‘Our prospects are brilliant.’

|

With one million barrels a day, Ghana will be promoted to the major league, alongside producers such as Indonesia. The country could easily become the third-largest oil player in the region, after Nigeria and number one producer Angola. And an eye-catcher in geopolitical terms. If the oil companies succeed in realising Ghana’s potential, the Gulf of Guinea will boost its daily oil production to over 6 million barrels, roughly 8 percent of the global total. Ghana’s stability will become a matter of international concern. That stability could be jeopardized if state oil revenues hit $2-4 billion a year, adding more than 20 percent to the national budget.

The rich oil reserves along Africa’s west coast have traditionally fuelled corruption and mismanagement. Ghana could prove the exception to the rule. For more than twenty years the country has been hailed as an oasis of calm in an otherwise unstable region. Its liberal reforms have made it the darling of foreign donors and investors. But the flood of petrodollars could tempt politicians to change course and extend state power, which is already considerable. ‘The Ghanaians are genuinely aiming to get it right, they want to set an example’, says the Dutch ambassador to Ghana, Lidi Remmelzwaal. ‘But good intentions alone will not be enough. The government wants to keep everybody happy. That won’t be an easy ride.’

Que sera, sera

The band on the sweeping terrace of the Shangri La Hotel in the Ghanaian capital of Accra launches into the resigned tones of Que sera, sera, Whatever will be, will be. The lyrics ringing out into the darkness of the surrounding night are symbolic of the way ordinary Ghanaians view the benefits the burgeoning oil industry may bring. ‘The money will go to the politicians, that’s certain. We won’t see a penny’, is what many local people say.

The country’s intellectual and political elite is similarly cautious. They have gathered in one of Accra’s most luxurious hotels for a two-day conference on biometric voter registration. Sagem of France is presenting a biosmartcard which it says can eliminate fraud in the upcoming 2012 general elections. This innovation, which has already proved its worth in elections following the bloody civil war in neighbouring Ivory Coast, appeals to the politicians and opinion-makers present in Accra. ‘The oil revenues have made bolstering the democratic election process a top priority,’ says Kofi Bentil of the liberal think tank IMANI, and one of the speakers at the conference. ‘Those petrodollars are an open invitation to people to get involved in politics and steal money, an incentive for keeping the state apparatus inefficient and developing a system that permits fraud. Just as in Nigeria and Angola, oil is bound to escalate the political tensions in Ghana.’

Those tensions can already be seen in some places, particularly in the coastal region facing the Jubilee field, where the population can see firsthand how the oil industry is gathering speed. In some cases expectations are unrealistically high. In West Ghana some villages are already reported to be quarreling over future oil money from the government. And there are reports of hot-headed youths threatening protest action and violence if no jobs are reserved for them. Some observers have even drawn comparisons with the violent Niger oil delta in Nigeria.

‘There are some ridiculous demands being made’, acknowledges Awulae Annor Abjaye III. He is the traditional leader of Western Nzema, the coastal region stretching from Takoradi to the border with Ivory Coast. ‘But we won’t take up arms like they did in Nigeria. People here know they can bring about change by voting in the elections. For our young people, too, that’s a better way than war and violence. But the government cannot be allowed to ignore us by saying that oil is a national treasure and that’s it. You can’t deny fishermen access to fishing grounds near the oil finds without offering them some kind of compensation. And any gas processing plant and petrochemical industry along the shoreline here will cost the people who live off the coconut palms their livelihood. The government has to compensate us. There must be schooling and work for the youth.’

New oil legislation

Concerns about the future of Ghana as an oil state are focused above all on the slow response of the government of president John Atta Mills that came to power in January 2009. There’s an urgent need for new legislation in order to ensure that future oil revenues are managed in a transparent way. And there needs to be greater clarity on the role of the national oil company GNPC. After all, bad examples of a mighty oil company in state hands lie close to hand. In Nigeria the NNPC is a breeding ground for corruption. And in Angola the highly competent national oil company Sonangol has grown into a mighty conglomerate with a wide range of international interests as well as a conduit for billions of petrodollars to the ruling elite.

But Ghana is taking a long time to decide on its policies. Of Ghana’s parliamentarians no one is more aware of this than Moses Asagra, Chairman of the parliamentary Committee for Energy Affairs. Asagra arrives more than an hour late for our appointment in Parliament House. ‘Large numbers of voters from my district came to my house to celebrate the inauguration of a minister and then I have to give them something to eat,’ he says apologetically.

| Black gold diggersThe most important shareholders of the Jubilee field are Tullow Oil (38%) and Kosmos Energy (23.5%). Other shareholders are Anadarko and Ghana’s national oil company GNPC. Jubilee is divided into two blocks: West Cape Three Points (operator Kosmos) and Deep Water Tano (operator Tullow). The full development of the field is estimated to cost between $ 3 and $ 6.6 billion. Other oil companies active in Ghana are ENI, Vitol, Aker and Hess. A useful report on Ghana’s blossoming oil industry can be found here. |

However, Ghana’s already running behind schedule, says Ishmael Edjekumhene. ‘Even if legislation is passed soon, it will be impossible to implement the new rules on time’, he says. Edjekumhene is director of an institution that has been schooling MPs in the finer points of oil contracts and royalty regimes. ‘Most of the parliamentarians knew almost nothing’, he says. ‘In the past they signed agreements with the oil companies without any regard for the small print. They allowed themselves to be dictated to entirely by GNPC.’

For this reason there is an ongoing risk of mismanagement and clientelism. Some observers point to indications that a new web of patronage is already being spun around the oil fields. But many Ghanaian policy makers regard their neighbouring countries with a slight feeling of superiority. They’re convinced their country won’t be the next to fall victim to the oil curse. ‘I hope we in Ghana can make the difference,’ says Kwaku Boateng at the Ministry for Energy. ‘We have discovered oil at a good time in the country’s history. We have democracy, government is functioning very well and we have a very active civil society. Ghana cannot afford to fail. And we have no excuse for failure. I think that we can succeed with the help of God.’

In any event Ghanaians have become increasingly assertive in their negotiations with foreign oil majors. Earlier this year the government halted the planned sale by Kosmos Energy of its 23.5% share in Jubilee to Exxon Mobil for $4 billion. The Ghanaians want to buy Kosmos’ stake themselves and sell part of it on, possibly to the Chinese. And the Ghanaian government wasn’t afraid to deploy strong-arm tactics to get Kosmos to see things their way. Kwaku Boateng is quite frank about this. ‘They [Kosmos] have other stakes in Ghana as well. So for their long-term interest in Ghana, it’s better for them to give government the opportunity to buy at a fair price.’

|

The Gold Coast Oil is no stranger to Ghana, a country that has acquired various nicknames down the years. A century or so ago the country was called ‘seepage coast’ because of the many places along its coastline where oil bubbled up through the ocean floor in shallow waters. For long years the black gold went unheeded because real gold claimed all the attention. For this reason the country’s British colonial masters named it the Gold Coast. Ghana’s early transition to independence, in 1957, earned it the soubriquet ‘The Black Star of Africa.’ The independent state’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, took much of the shine off that reputation with his policies to transform the country into an authoritarian socialist stronghold that stifled economic enterprise. Unexpectedly it was a mutineering air force general, Jerry Rawlings, who eventually put the country to rights. He paved the way for liberal reforms and democratic elections in 1992. The current president, Atta Mills, won the country’s fifth consecutive democratic elections in January 2009, taking over the reins of a relatively stable and prosperous country that is well-liked by foreign donors. But poor management of the expected flood of oil revenues could upset the status quo and propel Ghana into the chaos and elitist self-aggrandisement characteristic of the region as a whole. |

Discussion (0 comments)