IEA's 'changing energy landscape' portends a dysfunctional future

on

IEA's 'changing energy landscape' portends a dysfunctional future

Beyond the headline-grabbing projection that the United States will soon be the biggest producer of oil and gas, the latest energy outlook from the IEA is its gloomiest yet. The world will be well supplied with oil only if troubled Iraq becomes the second-largest exporter. Even so, oil prices will go on rising unless we enter another global recession. Carbon emissions will spew ever-faster into the atmosphere as we career towards being locked in to dangerous climate change; a credibility-stretching efficiency push could postpone this, but only by five years. Even by 2030, a billion people will lack electricity. Water is fast becoming a constraint on future energy supply. Perversely cheap natural gas will give US industry a competitive edge that will suck wealth away from OECD and emerging countries alike. And all this only if the IEA's arguably optimistic "central scenario" comes to pass. It could all end up a lot worse.

|

| IEA's Richard Jones (c) Switch Energy Project |

The messages in the 2012 edition of the IEA's WEO – seen by many as the most authoritative and influential annual projection of long-term energy trends – fall into two categories. The first consists of messages that we have heard before, but which have been updated to reflect another year of hindsight. It is the second category – messages we are hearing for the first time, or which have acquired a decisive new emphasis – that make this year's outlook especially interesting.

Launching the WEO in London last week, the executive director of the IEA, Maria van der Hoeven, said: "The global energy system is hugely complex, constructed of many interconnected parts that pull and push on one another. All of these changes need to be analysed and understood together if decisions are to be taken that put the world on track towards a secure, affordable and sustainable energy future . . . The global energy landscape is changing rapidly, and these changes will re-cast our expectation about the role of different countries, regions and fuels over the coming decades."

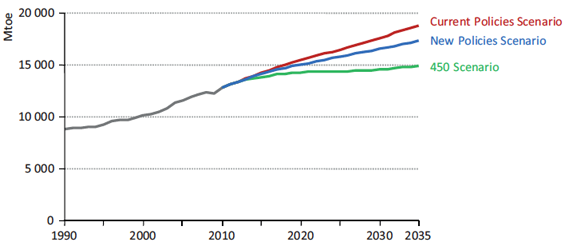

Inexorable growth in demand, carbon emissions and oil price

We knew already that the IEA expects global demand for energy to continue rising over the next two decades as the world's population grows, and as people in emerging economies aspire to the standards of living enjoyed by those who live in the wealthy economies of the OECD. In this year's WEO the projections are very similar to last year's: in the central New Policies Scenario (NPS), global energy demand grows by one-third over the period to 2035 (see chart 1), with China, India and the Middle East accounting for 60% of the increase – so the "centre of gravity" of global energy demand growth continues to move eastwards.

|

| Chart 1: Primary Energy Demand |

Another 'old' message is that the IEA believes that "the world is still failing to put the global energy system onto a more sustainable path". According to Fatih Birol, the agency's chief economist and lead author of the WEO, "last year [energy-related] carbon dioxide emissions increased by about 1 Giga tonne (Gt) to 31.2 Gt, which is a record high". Asked about the chances of keeping global warming within a 2°C rise on pre-industrial temperatures, he replied: "The chances are getting slimmer and slimmer. But we still hope that governments will change their position, because we need government support to address climate change."

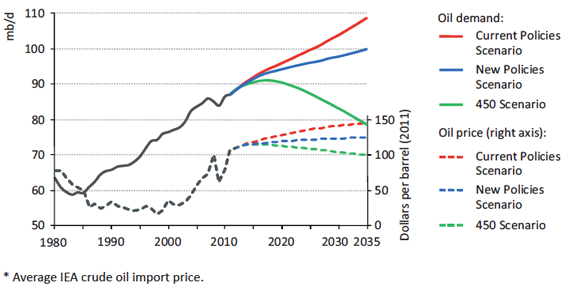

We have become used to high oil prices and it was no surprise to learn from Birol that "as of the beginning of this month, we have the highest oil price ever, on average, which plays a negative role in the global economic recovery efforts". This year's WEO assumes that average oil prices will stay high, increasing to $125/barrel in real terms (in 2011 dollars) by 2035 in the NPS (see chart 2).

|

| Chart 2: Oil demand and price |

So what's new?

The most dramatic new projection – reflected in headlines around the world – was that the United States is on track to become the world's largest producer of natural gas by 2015, overtaking Russia, and the largest producer of oil by 2017, overtaking Saudi Arabia for several years – with all that these developments imply. It is a result of a revolution in the production of unconventional oil that has followed on the heels of the revolution we have seen in production of unconventional gas.

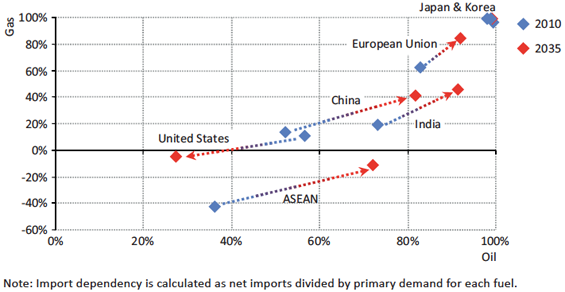

A major implication is that US energy import dependence will plummet from today's levels. Chart 3 shows how the projected US trend compares with projections for other countries; China, India and the European Union all move sharply in the other direction, while Japan, which already imports almost all its energy, stays more or less where it is now. As the WEO comments: "Together with efficiency measures that are set to curb oil consumption, this energy renaissance has far-reaching consequences for energy markets, trade and, potentially, even for energy security, geopolitics and the global economy."

|

| Chart 3: Import dependency |

Birol said that today's US oil imports of around 10 million barrels/day (b/d) were projected to fall to 4 million b/d within ten years, with 55% of the drop accounted for by rising indigenous production and as much as 45% "due to new efficiency standards for cars and trucks". By the end of the projection period, 2035, imports into the United States are only 3.4 million b/d and North America as a whole becomes a net exporter, as oil sands production in Canada grows to 4.3 million b/d.

This scenario of increasing self-sufficiency in oil in the US raises tricky geopolitical questions. One consequence would be that international oil flows would re-align, with around 90% of Middle East exports going to Asia. In the NPS a rising share of global oil trade has to flow through the Straits of Hormuz, the mouth of the Persian/Arabian Gulf (which Iran often threatens to blockade). As oil flows from the Middle East to Asia rise there will also be a growing reliance on the Straits of Malacca, with "oil transit volumes as a share of global trade rising from 32% in 2010 to 45% in 2035", according to the WEO.

Some analysts have argued that the US would have less of an incentive to protect these vital shipping routes, while China, for example, would increasingly feel the need to ensure their security.

The key change in US oil production has been the rise in production of unconventional oil – so-called "light tight oil" – using the same production techniques used for shale gas. The IEA sounds a note of caution about its projections, given how new this phenomenon still is and the uncertainties surrounding policy, especially in the face of public opposition to the production techniques used, especially hydraulic fracturing, or "fracking".

Over-reliance on Iraq?

Not that the world can relax about the adequacy of oil supply even if the IEA projections for the US are realised. Even with the projected increase in North American production, oil supply will only comfortably meet projected demand if another expected new development becomes reality: an increase in oil production in Iraq so large that it would make the nation the world's second-largest exporter by the 2030s, overtaking Russia. In other words, Iraq accounts for 45% of the growth in global production to 2035.

"Today Iraq is producing about 3 million b/d," said Birol, "and in our central scenario, which is significantly lower than the government's expectations, that goes to 6 million b/d by 2020 and to 8 million b/d by 2035. According to our numbers, Iraq's oil will be very cheap to produce – about 15 times cheaper than the Canadian oil sands for example and about 7 times lower than Russian oil production. And, unlike some of Iraq's neighbours, international companies and capital can go to Iraq for investment."

That said, Iraq remains a troubled country. As the WEO comments: "Development of the [oil and gas] sector will be determined by the speed at which substantial impediments to investment are removed, clarity on how Iraq plans to derive long-term value from its hydrocarbon wealth, international market conditions, and Iraq's success in consolidating political stability and developing its human resource base."

Birol concedes that failure would hinder Iraq's recovery and put global energy markets on course for "troubled waters". Because of the uncertainties, the IEA has developed a "Delayed Case" scenario for Iraq that results in a much less ambitious trajectory for oil production growth – capacity reaches 4 million b/d by 2020 and 5.3 million b/d in 2035. A global consequence would be oil prices nearly $15/b higher by 2035 than in the NPS.

Given the importance of oil prices, EER asked the IEA's deputy executive director Ambassador Richard Jones to explain how prices are determined for the WEO projections. He replied: "We only assume the prices, we don't project them. What we do is look at what the impact of certain policies will be. First we look at the impact on demand and ask: 'What kind of price will generate the supply?' Then we do an iteration. 'At that price would the demand be the same?' The answer is 'no – it would be affected in some way or another'. So we get new estimates of demand, of supply and price. The price is a solution of the model. It's designed to balance the assumptions that we make in other areas."

Gas price tensions

One trend that was already clear last year but which has gained new emphasis is the divergence of natural gas prices we are seeing in the three main gas-consuming regions: North America, Europe and Asia Pacific. Not only has this divergence persisted, it has grown wider. "At its lowest level in 2012," says the WEO, "natural gas in the United States traded at one-fifth of import prices in Europe and one-eighth of those in Japan." US gas prices have since risen but the differentials are still huge and likely to remain so for the foreseeable future.

The differentials are having some dramatic consequences. In the US, where gas prices are set by gas-on-gas competition, the gas glut caused by the unconventional gas revolution has pushed prices to levels not seen for a decade. Even today, Henry Hub prices are struggling to reach $3.50/MMBtu. At these levels, those electricity producers that can are switching from coal to gas.

This in turn has freed up cheap coal for export, much of which is finding its way to Europe, where gas prices are much higher, causing electricity generators there to switch from gas to coal. A bizarre result – though driven largely by market forces – is that in the US, where climate policy is virtually absent, greenhouse gas emissions have fallen sharply, whereas in Europe, where climate policy is almost an obsession, emissions are rising.

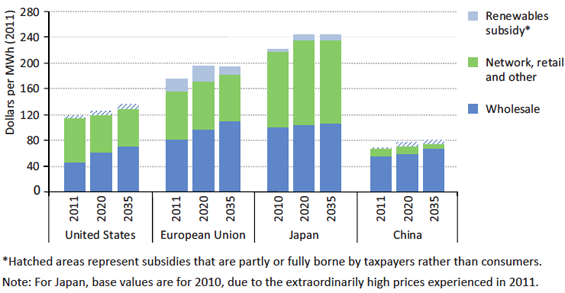

More fundamental is an industrial renaissance under way in the United States, based largely on cheap gas – and therefore cheap electricity – which is giving it a competitive advantage over other regions. This is particularly so in the case of Japan, which imports gas in the form of LNG, mainly under the terms of long-term contracts linked to oil prices. Average import price in recent months has been over $16/MMBtu, with prices under pressure as more LNG is imported to fill the gap left by the closure of most of Japan's nuclear power stations in the wake of last year's accident at Fukushima. Chart 4 shows how the IEA expects average household electricity prices to evolve in China, the United States, the European Union and Japan by 2035.

|

| Chart 4: Household electricity prices |

"That's one of the things that we hope people are paying attention to," Ambassador Jones told EER. "Energy is a factor of production and any time that you have a cost advantage in a factor of production means you're going to be competitive in that area. Electricity prices in the US and China are lower than in Europe and are likely to stay lower because gas prices are lower. And this isn't a question of subsidisation, it's strictly supply and demand."

Birol's view is that: "Oil-indexed pricing will be more and more under pressure. We have seen some countries make improvements even in existing contracts. We expect that there may be tough negotiations between the exporters and importers in new long-term contracts – and the hands of the importers will be stronger. It is far too early to say that the days of oil-indexed pricing are over, but we expect more flexibility in favour of importers."

Fall-out from Fukushima

Another trend re-shaping the global energy system that was already evident a year ago but which has gained emphasis over the past 12 months is the impact of the accident at Fukushima on the nuclear ambitions of several countries, including Japan, Germany, Switzerland and France. Even a year ago, few believed that we would see the closure of all Japan's 54 nuclear power stations by the middle of this year. Even today, only two plants have been allowed to re-start. Meanwhile, in the US and Canada, the competitiveness of nuclear is being challenged by the availability of cheap natural gas.

The IEA has therefore scaled back the anticipated role of nuclear power in the NPS. However, while projections are lower than in last year's WEO, nuclear output still grows in absolute terms in the NPS, as capacity expands in China, South Korea, India and Russia.

"To be honest with you, we are worried about what happens to nuclear energy," said Birol, "because in the absence of nuclear energy the 2°C [climate change trajectory] will be completely impossible."

Efficiency push

A key initiative in this year's WEO is a focus on energy efficiency and what can be done to make the most of this "hidden fuel". "Energy efficiency is a key option in the hands of policy-makers," said van der Hoeven, "offering cost-effective benefits with regard to energy security, emissions reduction and a host of other policy objectives. In the last year many energy-consuming countries – including China, the United States, the European Union and Japan – have announced new energy efficiency measures. But, despite this, current efforts fall well short of tapping the full potential."

The IEA has therefore come up with recommendations which, it believes, would, if effectively implemented, generate substantial benefits, including: halving the growth in global primary energy demand to 2035; making universal access to modern energy easier to achieve; and, crucially, extending the amount of time available to tackle climate change by five years.

Time to focus on adaptation?

Worthy as the IEA's work is, it is hard to escape the feeling that the 2°C climate change objective is not just unattainable but moving further out of our reach. Rivalling the bone-chilling effect of the WEO sentence that we began with is this one: "No more than one-third of proven reserves of fossil fuels can be consumed prior to 2050 if the world is to achieve the 2°C goal, unless carbon capture and storage (CCS) is widely deployed."

The IEA has been consistently over-optimistic about the prospects for CCS and there is little evidence that it will have any substantial impact on greenhouse gas emissions any time soon,

| It makes so much more sense to pay to avoid climate change than to adapt to it |

With this in mind, EER put the following question to Ambassador Jones: "Doesn't the 2°C target look rather hopeless? We're going into the [UN climate change] talks in Doha now, following on from Durban, Cancun and Copenhagen. Isn't it time to abandon the 2°C target and target adaptation?"

He replied: "Let me tell you: adaptation's more expensive. I don't want to abandon a less expensive alternative prematurely, just because politically people are having problems with it. I can't say that the recent hurricane [in the US] was caused by global warming, but all the models predict that there will be more such events. Think about the expense for that. It makes so much more sense to pay to avoid climate change than to adapt to it."

Discussion (0 comments)