Iraq: OPEC’s rising or falling star

on

Iraq: OPEC’s rising or falling star

Iraq stands as one of the major wildcards in the global energy market. Its ultimate success or failure as an oil powerhouse hinges on the outcome of its turbulent transition to either a functioning nation-state or a factious and violent status quo threatening its survival as one country. Despite the growing violence, Iraq hit the milestone of oil production last year for the first time in three decades. Will Iraq rise as OPEC’s next star?

|

| Iraqis work at the Rumaila oil refinery near Basra (c) Nabil al-Jurani / AP |

Iraq’s announcement of a new Integrated National Energy Strategy (INES) this June reinforces its ambitions for the hydrocarbon sector [4]. The INES envisions a surge in crude oil output from current 3 mbpd to 4.5 mbpd in 2014 and 9 mpbd by 2020 [5], which is more modest than Iraq’s earlier stated goal of 12 mbpd by 2017 [6]. Baghdad aims to increase this production without any input from its contentious Kurdish semi-autonomous region, relying only on new oil from the south [7]. But the ability to meet these oil output figures are threatened by the lack of a comprehensive hydrocarbon law, sabotage, and the decrepit state of energy infrastructure and bottlenecks that prevent delivery and processing of increased levels of oil output. A victim of years of wars, sanctions, and underinvestment, Iraq's infrastructure is barely able to move crude oil that it is currently producing and is unlikely to handle output beyond 3.5 mpbd from both the north and south without debottlenecking, modernization and expanded capacity. Bottlenecks exist in every part of Iraq’s energy value chain from export terminals, storage sites, pipelines, refineries, to ancillary services such as shortages of skilled manpower, water supplies, and electricity. This article assesses the relative status and bottlenecks of key assets of Iraq’s energy infrastructure in terms of condition and capacity, relative importance of infrastructure assets for increased oil production and exports, and significance of ancillary services.

Bottlenecks in the energy infrastructure

The main barrier to Iraq’s ability to compete in the global oil market is not production, but inadequate infrastructure. Sourcing nearly three-fourths of its crude from southern oilfields and the rest from northern fields near Kirkuk,

| Iraq has the potential to rival key oil producers in OPEC, aided by low production costs and easy geology |

|

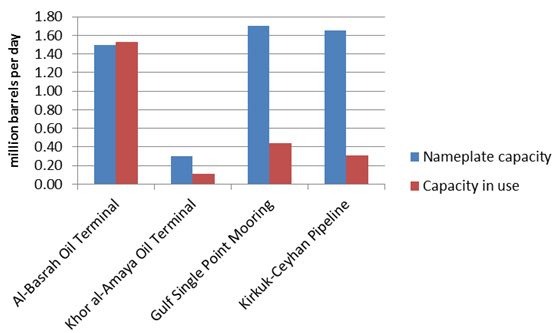

| Figure 1. Iraq’s major oil export infrastructure and capacities Source: “Iraq Energy Outlook,” IEA, October 2012, p. 22.; EIA Iraq Country Analysis, April 2, 2013 |

Rehabilitation and upgrades of the ABOT and KAAOT began in 2004 and are not yet finished [10]. To boost the capacity of export terminals, Iraq completed two single-point mooring (SPM) platforms in the south last year, with the capacity of 0.85 mbpd each [11] and it plans to build three additional SPMs [12]. Despite the growing capacity levels, exports through Iraq’s southern terminals have not increased as expected because of an antiquated pipeline system serving the terminals and technical issues with an SPM. In particular, several undersea oil pipelines that feed ABOT and KAAOT from the shore have been severely corroded, constraining their full capacity use [13]. Further, a delay in a launch of eight new storage tanks [14] in a major southern oil distribution hub Fao, which is a vital link between southern oilfields and offshore SPM platforms, and limited pumping capacity at Zubair added constraints to export increases [15]. Exposure of SPMs to bad weather is an additional challenge, particularly in the winter time. Removal of these bottlenecks and new capacity from additional SPMs will facilitate Iraq’s goal of ramping up the export capacity of southern terminals to 8 mbpd [16].

Compared to the export terminals in the south, the only functional cross-border pipeline from Kirkuk to the Turkish port of Ceyhan runs at relatively less capacity (see Figure 1) and faces greater constraints. First, Iraq’s crude oil pipeline system is old and corroded with limited export volume as a result of war damages and disrepair. A target of frequent attacks since the U.S. invasion, the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline carried only about 0.312 mbpd in 2012 out of its built-in capacity of 1.65 mbpd [17].

| Bottlenecks exist in every part of Iraq’s energy value chain |

The infrastructure is a key to success

In an effort to add more pipeline capacity to oil exports, Iraq signed an agreement with Jordan this spring to build a 1,680-kilometer pipeline, with a capacity of about 1 mbpd, from Basra to Jordan's Red Sea port of Aqaba [20]. Once built, the Iraq-Jordan oil line would be the first cross-border pipeline since the construction of the Iraq-Saudi Arabia pipeline in the 1980s, which was later confiscated by the Saudis as compensation for its neighbor’s debts. Another cross-border oil pipeline, Kirkuk-Banias, linking Iraq to Syria was in need of an entirely new pipeline sourcing oil from Basra [21] long before it was shut down with the U.S. invasion of Iraq and the start of the latest Syrian conflict.

Although Iraq seeks to reduce its dependence on export terminals in the Persian Gulf by shifting more exports to pipelines, the combined nameplate capacities of 2.5 mbpd of both Kirkuk-Ceyhan and Iraq-Jordan pipelines are not likely to match the size of the seaborne terminals in the near term. Given the ongoing insurgent attacks on the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline, the pipeline system is the most vulnerable component of Iraq’s export infrastructure. Therefore, the southern export route presents relatively greater opportunities to benefit the increased production and access to global markets.

As part of rehabilitation of the energy infrastructure, Iraq is channeling its efforts to upgrade its refineries. While Iraq’s refining capability is not yet export-oriented, it is an essential part of the energy infrastructure as domestic demand for oil derivative products is expected to increase.

| Water for oilfield injection is in highest demand in southern Iraq, where it is also the scarcest |

Other Hurdles

Addressing the immediate bottlenecks in Iraq’s energy export infrastructure is inseparable from other factors that chart the direction of the country’s energy industry, such as critically important ancillary services and the overall political climate. A problem that affects the political and economic climate in the country is a severe shortage of electricity. A reliable power supply is at the core of Iraq’s economic reconstruction as every component of its critical infrastructure – transportation systems, oil and gas production, distribution and export, water supplies, and power grid – is being rebuilt. But the country still gets only about six hours of electricity at most [24] as a result of wars, ongoing sabotage, and insufficient grid infrastructure and power capacity. Last year, the total power plant capacity was at 9 gigawatts (GW) from 15 GW that was needed to meet the country’s peak demand [25]. In turn, electricity shortages disrupt oil production and exports. As major increases in oil output and experts depend on heavy use of electricity, power failures prevented oil from being pumped into tankers in the south, at times bringing export terminals to a halt. At this juncture, energy companies in Iraq have no choice but to generate their own power to continue their operations.

Iraq’s energy sector is also in need of massive water supplies for injection into oilfields to keep reservoir pressure and to increase oil production. Because Iraq has not invested in the infrastructure to inject natural gas into oilfields, any increase in crude output will necessitate a corresponding rise in water injection. Water for oilfield injection is in highest demand in southern Iraq, where it is also the scarcest. Given the shortage of freshwater supplies in much of Iraq, Baghdad needs major investments in water pipelines to pump seawater to oilfields. According to an IEA scenario, “Iraq’s net water injection requirements will increase from 1.6 million bpd in 2011 to more than 12 million bpd in 2035 [26].” These estimates are based on oil production and water injection figures of Iraq’s Ministry of Oil and energy operators. Building of a Common Seawater Supply Facility (CSSF), a massive water-injection project that would treat seawater from the Persian Gulf and send it 100 kilometers inland for oil extraction use, will be important to Iraq’s ability to meet water needs for oil output. Once built, the CSSF would process up to 15 mbpd of seawater [27]. But this infrastructure is not expected to come online before 2017.

Finally, the broader political and security situation in the country continues to affect the energy industry. INES anticipates that Iraq will make major decisions on infrastructure improvement in coming years with a caveat that political and bureaucratic difficulties may get in the way. In fact, a prolonged lack of a legal regime guiding the exploitation of hydrocarbons in the country is still a bone of contention between the Kurdish semi-autonomous region and Baghdad. At the same time, poor governance, sectarian divisions, and terrorism, which claimed 4,137 lives and 9,865 injured since early 2013 [28], drove many skilled workers away from Iraq, including those critically needed for the energy sector. The escalating sectarian violence and the recurring sabotage of the oil pipeline system present an immediate risk to the modest progress that Iraq has made to restore its energy infrastructure.

- “Iraq Country Analysis,” Energy Information Administration, accessed August 13, 2013.

- “Iraq July Oil Exports 1.2% on Month to 2.324M B/D – Sources,” Wall Street Journal, August 1, 2013.

- “Iraq Country Analysis,” Energy Information Administration, accessed August 13, 2013.

- “Iraq’s Integrated National Energy Strategy,” Middle East Economic Survey, June 17, 2013.

- “Iraq Targets 4.5 Million Barrels a Day in 2014,” Al Arabiya, June 12, 2013.

- “Iraq to Increase Its Oil Production,” Alsumaria.tv, June 6, 2011.

- “Iraq Excluded Kurds from Ambitious 2014 Oil Output Target,” Hurriyet Daily News, June 18, 2013.

- “Iraq Country Analysis,” Energy Information Administration, accessed August 13, 2013.

- Carol Amon, “Iraq Oil Industry,” International Advisory Services Group, March 2011,

- John Lee, “Iraq Undecided on Basra Port Maintenance,” Iraq Business News, August 16, 2013.

- Kadhim Ajrash and Nayla Razzouk, “Iraq Plans to Start Second Offshore Export Facility Today,” Bloomberg Business Week, April 20, 2012.

- “Iraq Energy Outlook,” International Energy Agency, October 2012.

- JJ Sutherland, “Aging Oil Terminal Vital to Iraq’s Economy,” National Public Radio, June 20, 2009.

- “Iraq Completes Building Eight Oil Tanks on Gulf,” Al Shorfa, February 27, 2012.

- “Iraq: Selected Issues,” IMF Country Report, International Monetary Fund, July 2013, p. 6.

- “Iraq Energy Outlook,” International Energy Agency, October 2012.

- Ibid.

- “Oil Market Report,” International Energy Agency, February 13, 2013.

- “Iraq Reopens Strategic Pipeline,” Iraq Business News, December 6, 2012.

- Hassan Hafidh, “Iraq Begins Design of Pipeline to Jordan,” Wall Street Journal, February 28, 2013.

- Issam al-Chalabi, “Iraq’s Oil Export Outlets,” Middle East Economic Survey, November 3, 2009.

- Ibid.

- Kadhim Ajrash, “Iraq to Invest $130 Billion in Upstream Sector Over 5 Years,” Bloomberg, March 16, 2013.

- Ali Abel Sadah, “Iraq Suffers Power Crisis as Temperatures Soar,” Al Monitor, July 31, 2013.

- “Iraq Energy Outlook,” International Energy Agency, October 2012, p. 30.

- Ibid, p. 67.

- “Iraq Country Analysis,” Energy Information Administration, accessed August 13, 2013.

- “UN Casualty Figures for July,” United Nations, August 1, 2013.

Discussion (0 comments)