Pressure mounts to develop UK shale, as drillers jostle for acreage

on

Pressure mounts to develop UK shale, as drillers jostle for acreage

In the UK politicians are becoming excited over the prospects for shale development, anticipating lower energy prices, improved energy security, higher growth and jobs, lower emissions and increased tax revenue, with many of the early fears apparently proving unfounded. However concerns remain over lengthy and complex planning rules and public protest.

|

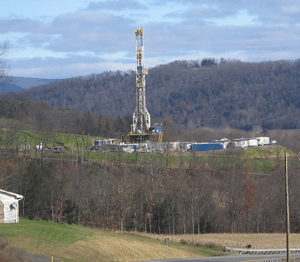

| Derrick and platform of drilling gas wells in Marcellus Shale - Pennsylvania - source Wikipedia |

Eager UK politicians remain frustrated at current slow progress in shale drilling, and appear committed to do something about it. Since the removal of a moratorium on hydraulic fracturing in 2012, the UK has not yet received or approved any applications for exploratory drilling, although Cuadrilla – headed by ex-BP chief John Browne - says it will soon apply to drill and hydraulically fracture four wells in Fylde, Northwest England, where it holds an exploration and production license. More are expected to follow – IGas already produces about 3,000b/d conventionally onshore UK, and with unconventional licenses now covering over 1 million acres, plus backing from GdF, it is expected to proceed with planning applications in its license areas soon.

So far concern over slow progress has prompted proposed tax measures that George Osborne, the UK finance minister, called “the most generous for shale in the world”. More recently ministers announced plans to give energy companies the right to run shale gas pipelines under private land, restricting the need for planning permission to drilling sites. Other rule changes are being considered to make drilling easier and ensure there is not an overburden of red tape and regulation, bringing the lengthy planning process – which can easily take 4 years - down to manageable levels.

The UK government is enthusiastic for several reasons. It believes shale gas holds the promise of lower energy prices, with consultants Poyry, for example, forecasting gas prices up to 14% lower on average from 2020 to 2050 if development goes ahead - others say prices could be cut by as much as 30%. With an eye on falling US CO2 emissions, UK politicians also believe shale gas could be an efficient means of meeting emissions targets, compared to the £2 billion a year (and rising) subsidies it spends on renewables. There are also substantial advantages to the UK in reducing energy import costs and improving energy security, against a background of declining North Sea production. “Of all European countries, the UK’s North Sea experience provides the best infrastructure and capabilities necessary to exploit this resource”, said a senior Platts editor.

Shale gas is also expected to be good for development and jobs. A recent government report on onshore licensing concluded that unconventional oil and gas could quickly generate 32,000 new jobs, many of which would go to relatively deprived regions. Others are even more optimistic - in April a report from the UK Onshore Operators Group (UKOOG) predicted shale gas development could create over 64,000 jobs and generate investment of £33 billion over an 18 year time frame.

Fears associated with fracking are being challenged too, with the Institution of Mechanical Engineers and leading operators emphasising recently that they believe shale gas exploitation and production can be done safely in the UK. Politicians are quick to point out that the record of shale gas drilling in the US is almost blemish free, while UK regulation is much tougher. With the pending closure of the last of the UK’s coal mines some see domestic shale gas as a cleaner and safer potential replacement.

Until more test drilling has been carried out, precise reserves and recovery costs will be uncertain, but some analysts are already suggesting the 1000 trillion-plus of recoverable cubic feet of gas, maybe accompanied by billions of barrels of oil.

Community credentials

A focus on local incentives, including £100,000 per well and a 1% revenue tariff, as well as local retention of business rates, is spurring shale gas’ UK community credentials. UKOOG estimate that this could generate more than £1.1bn over a 25 year period for local communities, or £5-£10 million per site. Still more could be offered, with industry group, Energy UK, suggesting possible joint ventures with Councils and residents, including drillers handing out shares in their companies.

While national media has tended to focus on protests, national opinion polls are generally positive, and – perhaps with the incentives in mind - local communities even more so. The Green party, which is the only one to oppose fracking, came last with 4% of votes cast in a recent Fylde Borough council by-election – the hotspot for Cuadrilla’s proposed development. Online petitions opposing drilling at sites in northern and southern England have all failed to garner more than a few hundred signatures.

In early May a House of Lords report urged the Government to “go all out for shale” and find solutions to the current slow progress, providing robust but quickly navigable regulation. But it also said there should be no short cuts for developers, with well inspectors independent, rather than being employed by the drilling company.

Moving targets

Concerned over the EU’s international competitiveness, and worried by the fragmentation of the internal market brought about by national subsidy schemes for renewables, the European Commission’s 2030 climate and energy package dropped its renewable targets, providing instead a 40% emissions reduction target by 2030. At the same time, reform of the EU Emission Trading Scheme is likely to see carbon prices rising. Both measures will favour cleaner fossil fuels, adding to the attraction of shale gas development.

“With a carbon target rather than a technology target after 2020, shale gas becomes more attractive due to its low carbon credentials. It may be a fossil fuel but it is a clean one,” said shale gas expert, Nick Grealy. Gas produces about half the CO2 of coal and none of the other toxic pollutants such as sulphur dioxide. “In Europe policy makers are warming to the merits of shale gas, but remain wary of a sceptical and ill-informed public as they look on across the channel and hope the English don’t screw it up.”

The UK government’s current overall target aims for 11% of all energy consumed to come from renewable sources by 2020. If re-elected the current government are expected to follow Europe and swap renewable targets for emissions ones, and possibly a carbon tax too according to Nick, but not until after the general election in mid-2015. While there is strong support for shale gas among all the main political parties, the Labour party is thought less likely to favour a market based system. “It’s not a question of renewables or shale gas – the gas is an essential backup for intermittent renewables and it will replace either coal or LNG transported half way around the world,” said Nick.

The UK is increasingly making its views felt in Europe, including a recent submission to the European Commission from Prime Minister, David Cameron. There is also bilateral cooperation, with Poland and the UK working on a review of the potential impacts of shale gas, and how it might help the EU reduce its dependence on imported fossil fuels. Europe’s heavy reliance on Russian gas has pushed the issue of energy security back up the agenda, with member states pushing the commission to review the issue by June, which should also be favourable to shale gas.

Alongside the UK, the International Energy Agency (IEA) is also urging greater development, pointing out that countries such as Austria and The Netherlands – traditionally a major gas-producer – among others, have great potential. Maria van der Hoeven, executive director of the IEA, recently noted that “it is time to re-assess [Europe’s] energy security and to look at different cost-effective pathways to guide the transition”. Nick Grealey believes the current European energy commissioner, Günther Oettinger, is “open to changing his mind when events change”.

Given the rapid switch in focus from shale gas to shale oil in the US, talk is increasingly moving to the liquids potential of UK acreage. The Platts editor noted this would mean development would not depend on regional gas prices, but would be driven by Brent-related international oil prices, providing an even stronger incentive for shale development. Meanwhile in the US, drill rig counts and costs keep going down, wells per pad, laterals and frack stages keep rising, and production for both oil and gas is soaring. “Europeans are very naive to believe this is just an American opportunity,” said Nick.

Discussion (0 comments)