Shale gas battle in Bulgaria - high stakes for Europe

on

Shale gas battle in Bulgaria - high stakes for Europe

The recent announcement from the Bulgarian Ministry of Energy that US oil company Chevron has been awarded a shale gas exploration licence in the north of the country, has brought a new urgency to the long-simmering debate on shale gas in Bulgaria. The Bulgarians are asking themselves whether shale gas would be the best way of achieving greater energy independence and what its potential environmental hazards might be. For the Russians in particular there is more at stake than may be apparent at first sight. Atanas Georgiev reports from Sofia.

|

| US ambassador to Bulgaria H.E. James Warlick (left) frequently discusses energy matters with Bulgarian Prime Minister Boyko Borissov (photo: US Embassy, Bulgaria) |

The Bulgarian government is extremely enthusiastic about the prospects of shale gas for Bulgaria. Energy Minister Traycho Traykov has even said that 1 trillion (1,000 billion) cubic metres of gas could be found in Bulgaria, which would cover the country’s consumption for 300 years. The government claims that shale gas production would improve diversification of supply and could bring various economic benefits: domestic gas supply at reasonable prices, revenue from royalties and taxes, increased employment, investments in infrastructure and improved geological knowledge.

Yet the government’s support for shale gas cannot be viewed in isolation from geopolitical considerations. The ruling rightist party GERB and Prime Minister Boyko Borissov tend to have good relations with the US, whereas the opposition Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP) is traditionally more aligned with Russia. Shale gas development is heavily pushed by US companies and the US government in Eastern Europe, both for commercial and political reasons – and just as heavily resisted by Gazprom and the Russian government. With presidential and local elections coming up in October, the shale gas issue will no doubt remain strongly politicized for the time being.

Growth potential

Bulgaria is a small gas consumer. In the last ten years its consumption averaged 3 bcm (billion m3) annually, with the global economic crisis pushing this number down to almost 2.5 bcm in 2009 – the lowest level since 1976. To compare, a country like Belgium uses some 20 bcm. In Europe only Sweden consumes less gas than Bulgaria.

However, natural gas has a lot of growth potential in Bulgaria. Currently only about 3% of households use natural gas, as this market segment was not developed until the 1990s, but the Energy Strategy of Bulgaria until 2020, which was adopted this year, envisions a further development of gasification for household consumption. District heating companies have been gradually replacing other fossil fuels with natural gas, and there are plans for construction of the first natural gas power plants. There are also plans for building gas interconnectors to Romania, Greece, Serbia and Turkey. And last but not least, the planned gas pipelines Nabucco and South Stream, if they are built, will both cross the country, promising the possibility of new connections to the gas network, for instance for some of the municipalities that now have no access to gas and no distribution networks. All of these developments augur well for gas consumption in the coming years.

With gas use likely to grow, diversification is becoming an all the more urgent issue. Bulgarians of course remember the Ukranian-Russian gas crisis of 2009 when the country was left without imports for a month. With Ukrainian-Russian relations cooling off again, there are fears that another crisis may occur during this winter or later on.

No market

There currently is no real gas market in Bulgaria. The country depends for 95% of its consumption on Russian gas, which is all supplied by one wholesale supplier, Gazprom, transported via one pipeline (through Ukraine), and bought and resold by Bulgargaz, a subsidiary of the state-owned Bulgarian Energy Holding EAD. The remaining 5% of supplies is also delivered to Bulgargaz, which likes to include alternative sources in the mix to keep prices down. Bulgargaz sells the gas at regulated prices to industrial consumers, power companies and households. This means that there is no diversication whatsoever in the national gas market, making business and households extremely vulnerable to supply crises and price changes.

Domestic production from conventional wells amounted to just 74 million bcm last year, according to data from the energy ministry. Currently known conventional gas reserves are a mere 10.5 bcm.

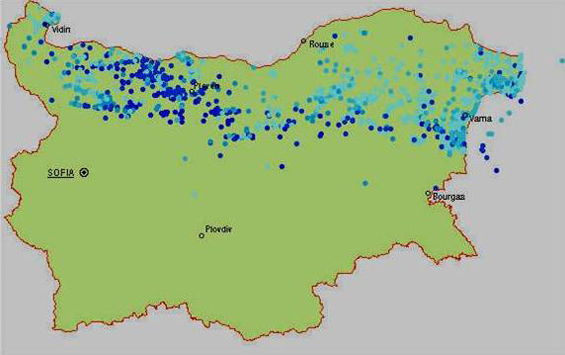

The lack of large oil and gas fields in Bulgaria has always been regarded as a disadvantage for the country. Most of the exploration drilling was done after 1947 in Northern Bulgaria and the Black Sea and currently the total number of wells is about 1,000. Local production of natural gas from the Black Sea coast, operated by the Edinburgh-based company Melrose Resources, almost reached 7% of national consumption in 2008. Currently the company is exploring new fields, but there is no sign that significant discoveries will be made.

|

| Currently there are about 1000 conventional oil and gas wells in Bulgaria (photo: Ministry of Economy, Energy and Tourism, Bulgaria) |

So this explains the euphoria among some energy experts when the shale gas potential of Bulgaria became known in the last year or so. After the rise of shale gas exploration and production in the United States and the start of exploration in Poland, American companies turned their attention on Bulgaria. In June, Chevron became the first company to receive a (5-year) exploration license. The company has announced that it expects technically recoverable shale gas reserves in Northeastern Bulgaria to amount to between 300 bcm and 1 trillion cubic meters. This is colossal in comparison with the current gas consumption and reserves of the country. The Ministry is currently preparing for a second concession procedure for shale gas exploration in Northern Bulgaria.

Extremely difficult

Energy Minister Traycho Traykov has said that domestic production of shale gas may turn out to be cheaper than alternatives. The energy ministry has also pointed out that Chevron pays €30 million for its drilling concession. This is more than the revenue from all other gas concessions combined. In addition, shale gas drilling, the Ministry says, will have other positive economic effects, e.g. on employment and on the infrastructure in the drilling region.

However, the Minister’s price comparison seems rather premature. Shale gas production is not expected to start until at least five years after the exploratory drilling. Moreover, it is difficult to make a comparison with Russian gas prices, as there is still no renewal of the long-term contracts of Bulgargaz, with Gazprom and its subsidiaries which expire at the end of 2012. Gas prices are also hard to predict because the future liberalization of the national gas will bring new logic to price formation and contracting. Analysts expect that the construction of Nabucco and of the planned interconnectors to Bulgaria’s neighbouring countries will introduce new suppliers to the market. If this happens, spot markets are expected to grow and replace at least some of the long-term contracts.

One of the most talked-about options is the IGB (Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria) that could be used to supply gas from the Revithoussa LNG terminal. Its construction is expected to start next year and it will be connected to the planned ITGI (Interconnector Turkey-Greece-Italy) pipeline as well. In addition, Bulgaria has an understanding with Azerbaijan for 1 bcm of gas supplies annually, but currently this gas cannot be transported, as the only pipeline connecting the two countries is owned by Gazprom, which refuses to allow such a deal. IGB and ITGI could make this import possible and thereby support the liberalization of the market. If these plans come through, alternative sources may have a better price than local ones. Ironically, shale gas production in the US has already affected European markets by decreasing global spot prices of LNG, and if this trend is maintained, it could make shale gas production in Europe relatively expensive. All these factors make economic analysis extremely difficult and suggest that decisions taken now, out of short-term considerations, could prove to be disadvantageous in the medium and long run.

It is also not certain whether diversification is best served by going for shale gas. It may turn out that better diversification results could be achieved with decisive action on alternative gas supply routes (interconnectors, Nabucco, South Stream, etc.), alternative sources (Caspian gas, LNG) or alternative suppliers (competitors to the current monopoly supplier Gazprom and its subsidiaries). All these gas supply diversification options have been widely discussed and could be implemented in a reasonable time frame. Moreover, they are conventional solutions and none of them includes environmental risks as shale gas does.

New players

Any developments in shale gas in Bulgaria will have geopolitical and economic repercussions that extend beyond the immediate commercial impacts. In particular for Russia, the future of the Bulgarian gas market is of some importance. Even though currently Bulgarian national consumption amounts to about 1.6% of Gazprom’s exports, the country has an important geostrategic position - both for the

| Shale gas production by American companies will bring new players into this market that may challenge the hegemony of the Russians |

What should be noted in this context is that shale gas exploration and production by American companies in Bulgaria will not just increase domestic production, it will also bring new players into this market that may challenge the hegemony of the Russians. It could also lead to increased demands for liberalization.

Energy routes

Currently the strongest opposition to shale gas in Bulgaria is motivated by environmental fears. Some of the environmental arguments are used by the political opponents of shale gas, but this does not mean that these concerns are not genuine. The shale-gas rich region of Bulgaria is in the North-Eastern part of the country. This is an important agricultural region. In addition, communities here get their drinking water from underground aquifers. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has not given a clear answer yet as to whether the process of hydraulic fracturing can be done safely without affecting underground waters.

A report published by the Atlantic Council in June describes some of the known risks related to shale gas drilling. The report, a result of two US-EU meetings of industry and institutional experts, suggests that environmental hazards exist and the proper way to deal with them is to compensate affected stakeholders. In the case of remote farms in the US this could mean providing a reserve water source if the primary one is damaged, but this could not be applied so easily to larger communities in Europe, where density of population in gas-rich regions is larger. The report also points out that exploration and production of shale gas should observe national and European legislation related to surface and underground water sources. The most important piece of legislation in this field is the European Water Framework Directive (WFD), which requires that EU member states ensure ‘the least possible changes to good groundwater status, given impacts that could not reasonably have been avoided due to the nature of the human activity or pollution’.

Ultimately the government will have to decide, with the active participation of society, which options to pursue: conventional energy diversification policies or unconventional gas exploration and production. Poland is now cited as a model for shale gas exploration, but the case of Bulgaria is somewhat different for several reasons. First, the political bias against Russia is not so strong in Bulgaria. Energy cooperation with Russia has been a fact of life and most probably will be for a long time to come. Secondly, the geographical position of Bulgaria is better in terms of energy routes – the country is on the path of both Nabucco and South Stream, with prospects for several interconnectors connecting it to other sources as well. Bulgaria also has the possibility to use more renewable sources for electricity and heat production and increase its energy efficiency potential. Thus, diversifying energy supplies by banking on shale gas may not be the most logical route to take.

|

Who is Atanas Georgiev? Atanas Georgiev is assistant professor at the Faculty of Economics and Business Administration (FEBA) at Sofia University. He coordinates the Master Programme “Economics and Management in Energy, Infrastructure, and Utilities”. From 2005 to 2009 he worked at Uconomics Ltd., first as a consultant in energy sector restructuring, later as managing editor of the Bulgarian “Utilities” Magazine and programme manager for a number of trainings and conferences in the fields of energy, infrastructure and utilities. He has published a number of articles about the energy and utilities sector. Since January 2010, he has become managing editor of publics.bg – an online professional medium supporting the development of public services and energy in Bulgaria. See also his earlier article on the Bulgarian gas market for European Energy Review: Bulgaria - gas consumer or future gas hub? |

Discussion (0 comments)