The Southern Gas Corridor: Reaching the Home Stretch

on

Who will win the first leg of the pipeline race in South East Europe?

The Southern Gas Corridor: Reaching the Home Stretch

After many years of speculation about possible gas pipelines to be built in the so-called Southern Corridor, a first likely winner will be announced shortly. It probably won't be the EU-backed Nabucco nor the Russian-backed South Stream, but the much less ambitious Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), owned by Eon, Statoil and EGL. This is the prediction of Friedbert Pflüger, Director of the European Centre for Energy and Resource Security (EUCERS) at King's College London. In this article written for EER, Pflüger, who served for twenty years as a Member of Parliament and was State Secretary in the first Merkel government, explains why the Southern Gas Corridor is crucial to Europe's energy future and how it is likely to develop.

|

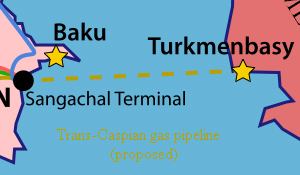

| The Trans-Caspian gas pipeline (click for complete image) |

There have been lengthy speculations in recent years about the Southern Gas Corridor – seemingly endless discussions about various pipeline concepts, and their geopolitical meaning and economic feasibility. This is understandable, as the different projects have numerous stakeholders, including transit governments, gas buyers, transportation companies and international financial institutions that are involved in project-financing.

But these discussions will soon come to an end – at least for the time being. This is because the consortium operating the Shah Deniz II gas field in Azerbaijan, which needs to come on stream by 2018-2020, will shortly have to announce how they will arrange for the transport and sale of 10 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas annually – the first and, for now, the only major non-Russian gas supply that will traverse the Southern Corridor. Taking into account all the pros and cons of the pipeline projects downstream of Turkey, the most likely winner of the first leg of the race will not be Nabucco, the Interconnector Turkey-Greece-Italy (ITGI), or South Stream but rather the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP).

The History of the Southern Corridor Debate

To explain the significance of this outcome, we first need to take a brief look at the history of the Southern Gas Corridor. Following the break-up of the former Soviet Union, the United States and the Turkish government pursued a strong policy to support an independent development of the emerging new economies in Central Asia and the Caucasus region. This drive was underpinned by the US State Department's 1997 Caspian Basin Report, which estimated huge reserves of gas and oil. There was a strong emphasis on the common Turkic cultural, historical and linguistic links that stretch across Central Asia and a strong advocacy for the development of east-to-west oil and gas pipelines. This would enable the oil and gas producing Caspian and Central Asian countries to export their hydrocarbons without traversing the territory of the Russian Federation or Iran. Although the results were mixed, they did lead to the 1,764 kilometer one million barrel/day Baku-Tiblisi-Ceyhan Pipeline.

Another project concurrently promoted by the US government at that time was the Trans-Caspian-Pipeline (TCP), designed to deliver gas from Turkmenistan to EU-markets via the territories of Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey. In June 1998, a consortium including Amoco, GE Capital and Bechtel Enterprises came together to sponsor the TCP project, which involved a 750-mile new-build pipeline

| With the discovery of the Shah Deniz Field, the core "driver" behind the Southern Gas Corridor concept shifted from Turkmenistan to Azerbaijan |

With the discovery of the Shah Deniz Field, the core "driver" behind the Southern Gas Corridor concept shifted from Turkmenistan to Azerbaijan. Shah Deniz now provided a strong commercial driver to implement the original US-objective to develop a large-scale transportation solution to link Caspian gas to European markets.

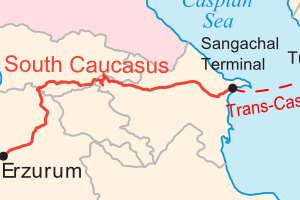

As a result, instead of TCP another project became reality: the South Caucasus Pipeline (SCP), which came onstream in 2006. The SCP, owned by BP, Statoil, SOCAR, Lukoil, Total, TPAO (Turkey) and NICO (Iran), transports gas from Shah Deniz through Azerbaijan and Georgia to Turkey, where it interconnects with a new-build pipeline constructed by BOTAS to Erzurum. It has a capacity of 8.8 bcm, which might be expanded to 20 bcm after 2012.

The Shah Deniz Field has proven recoverable gas reserves of 1.2 trillion cubic meters (tcm) with considerable upside potential. To compare: gas consumption of Germany is about 80 bcm per year. The field has been developed in two phases with the first one already delivering approximately 6.8 bcm annually to Turkey and 3.2 bcm into the local markets of Azerbaijan and Georgia.

The second phase of Shah Deniz is most relevant now for the upcoming decisions on the Southern Corridor pipeline. A final investment decision for Shah Deniz II is expected in 2013, once the transportation route to Europe (including interconnectors) has been selected and host government risks allocated. Before a final decision is taken by the Shah Deniz consortium, it will also be necessary that commitments along the transportation value chain, including with downstream off-takers and transportation providers, are finalized.

Gas volumes from the second phase are expected to be 17.6 bcm per year, with 1.6 bcm being delivered to the local markets in Azerbaijan and Georgia, 6 bcm to Turkey and the balance of 10 bcm dedicated to the markets in Southeastern Europe and the EU (note that Turkey’s 6 bcm may also be re-exported by Botas to yield a potential 16 bcm to Europe).

The Shah Deniz Field is operated by BP, which has a share of 25.5% and is also the technical operator of the SCP Pipeline. Statoil's share is the same and the Norwegians are the commercial operators of SCP. The other partners include the state-owned Azerbaijan company SOCAR, French Total, LukAgip (a joint venture of Italian ENI and Russian Lukoil) and NIOC of Iran, who all have a 10% share, and TPAO of Turkey, which has 9%.

EU Becomes a Supporter of the Southern Corridor Project

The geostrategic aim developed by the US started to receive strong support from the European Union following the gas supply disruptions in early January 2006, when serious disputes arose between Russia and Ukraine over gas prices, payments and supplies. The transport of gas was cut off for four days, which led to serious shortages in some Eastern European countries and which, even more importantly, demonstrated the enormous dependence of Europe on Russian gas imports.

Given the political panic following the cut-offs and considering the fact that Europe's own reserves would further decline in the future, thus increasing the dependence on Russian gas even more, the EU

| 'Today eight Member States are reliant on just one supplier for 100% of their gas needs - this is a problem we must address' |

Here is a brief chronology of the events that followed:

- On 13 November 2008 the EU Commission published its EU Security and Solidarity Action Plan outlining its initiative for the Southern Gas Corridor. It signalled that Brussels would support more independence from Russia as was made clear by EU Commission President José Manuel Barroso's statement that the EU needs “a collective approach to key infrastructure to diversify our energy supply – pipelines in particular. Today eight Member States are reliant on just one supplier for 100% of their gas needs – this is a problem we must address. We must shield European citizens from the risk that external supplies cannot honour their commitments.”

- On 1 January 2009 a second gas dispute between Russia and Ukraine broke out, with deliveries resuming on January 20th, albeit at higher prices. As a result, the fears of a potential Russian energy blackmail in the future intensified.

- On 8 May 2009 representatives of key Central Asian and Caspian countries, Turkey, and Egypt signed a declaration of support for the Southern Gas Corridor at the Prague Summit. The Prague Summit’s official declaration considered "the Southern Corridor concept as a modern Silk Road, interconnecting countries and people from different regions and establishing the adequate framework necessary for encouraging trade, multidirectional exchange of know-how, technologies and experience." Here, the Nabucco pipeline project, first proposed in 2002, was expected to play a key role. Consisting of a consortium of six companies with equal shares of 16,67%, including Austria’s OMV, Hungary’s MOL Group, Bulgaria’s Bulgargaz, Romania’s Transgaz, Turkey’s BOTAS, and Germany’s RWE, the pipeline would be expected to deliver gas from the Caspian Sea and Middle East regions to Europe with a throughput capacity of 31 bcm/year.

- On 13 January 2011 EU Commission President Barroso, accompanied by EU Energy Commissioner Günther Oettinger, signed a Joint Declaration with the President of Azerbaijan to bring gas from Shah Deniz Phase II as well as additional gas from Baku to Europe.

Nord and South Stream

|

| The four Southern Corridor gas pipeline projects compared (click for larger image) |

With Nord Stream, the Russians demonstrated their ability to break their dependence on the Ukraine, Poland and Belarus as transit countries and emphasized that the EU will remain the main gas market for them. There is already talk of Nord Stream transportation capacity being expanded by an additional (third) pipeline.

Apart from Nord Stream, the Russians also introduced South Stream as a direct reaction to Europe's Nabucco visions, which they believed to be a serious threat to their monopoly to supply Europe with pipeline gas. Gazprom (50%), ENI (20%), EDF and Wintershall (15% each) formed a consortium to transport 63 bcm of gas via a subsea Black Sea pipeline through southeast Europe to Hungary and Austria.

While Gazprom stresses time and again that this pipeline is not meant to outcompete the existing Southern Gas Corridor projects, chiefly Nabucco, its target markets are roughly the same as Nabucco’s. Although Gazprom claims that South Stream will not bring new volumes of gas to the EU but merely seeks to redirect already contracted volumes, it still has to explain why it is prepared to significantly erode the netback value of its gas by paying for a new-build €16 billion project. Why invest so much money for the shipment of old gas through a new pipeline?

Even after the German decision to phase out nuclear power by 2022, and even with the most optimistic forecasts, it is hardly economical to build 63 bcm of new capacity in addition to the existing Jamal transit route through the Ukraine and the 55 bcm added by Nord Stream. It seems more likely that the Russian project South Stream is mainly designed to undermine the ability of the European Union's Southern Gas Corridor projects to contribute to a diversification of its gas supplies.

Moreover it is crystal clear that South Stream also serves the aim to put additional pressure on the Ukraine to behave in Moscow’s interest. In late December 2011, Gazprom's CEO Miller said that “South

| With Nord Stream, the Russians demonstrated their ability to break their dependence on the Ukraine, Poland and Belarus and emphasized that the EU will remain the main gas market for them |

Nabucco's Declining Chances

While EU member states agree that gas supply diversification is necessary, they do not agree on how to achieve this goal. South Stream aside, even other diversification projects that the Europeans themselves came up with could not be implemented if Nabucco were realized. There simply would not be enough supply.

So, Nabucco does not only face opposition from Gazprom, it also meets with growing skepticism within the EU, for the following reasons.

- Many EU countries, among them Germany and Italy, have a strong interest in avoiding confrontation with Moscow, which they consider to be a reliable energy partner. Is Nabucco, with its 31 bcm capacity, not a provocation to the Russian partners with whom they have constructively worked together for the past decades and whose gas supply seems to be more reliable than gas shipped through many other countries with different levels of stability and competing interests?

- Especially after German utility RWE (which has always been the driving force of the Nabucco consortium) in the summer of 2011 signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Gazprom concerning the joint construction of new (gas-fired) power plants, doubts about the seriousness of RWE's commitment to Nabucco became widespread. This despite the fact that RWE's CEO Jürgen Grossmann stated repeatedly that the new cooperation with Gazprom would not change the company’s policies towards Nabucco. These doubts have not diminished after the recent news that the deal between RWE and Gasprom will not be realized.

- The main problem with Nabucco, though, was (and is) of a different kind. The question is where should the gas come from to fill the pipeline? The Nabucco shareholders appear to have presented Shah Deniz II sellers an offer to purchase 21 bcm of gas for shipment through Nabucco. The catch is that Shah Deniz has only 10 bcm to sell. Even if the 6 bcm that is sold to BOTAS (Turkey) is added for re-export, the total volume of available gas is only 16 bcm. Without a doubt, there are other potential sources of gas, namely in Northern Iraq or perhaps in the future in Iran, but for the responsible planning of a complex multi-billion Euro pipeline project, concrete availability of gas is needed within a definite timeframe. The project must guarantee profit to the shareholders and banks. So it has to be economical and not just a geostrategic idea. Large energy projects are rarely driven by downstream interests, convincing as they may appear. It is an error to believe that just because the political will and the strategic rationale for a certain project are strong enough the gas will flow. Political will is an important condition for realizing a project, but certainly not a sufficient one.

Thus, only if the EU is prepared to put its own (taxpayer) funds into the project and wait for future gas reserves to be produced in the Central Asian/Caspian/Middle East area could Nabucco become economically feasible. So far, though, it seems that only China is capable of realizing projects driven solely by downstream interest. Beijing financed and constructed the Turkmenistan-China pipeline by itself, thereby becoming the sole "driver" of the project. Perhaps there was a certain moment in which it was possible to purchase additional gas for Nabucco. But the window of opportunity to supplement the 10 bcm from Shah Deniz II, for example from the Kurdish Region of Iraq where huge reserves have been discovered and where the political will to ship that gas to Europe is strong, has been missed. The unity and political will within the EU has not been strong enough to convince the various players to invest and connect the dots in time. - As for the possibility that Turkmen volumes of gas may be added to the Shah Deniz II gas, it is necessary to consider the following obstacles. First, it is very unlikely that the Russian Federation will lift its objections to the implementation of a Trans-Caspian Pipeline due to environmental reasons. Given the large-scale gas transportation commitments that Ashgabat currently has via Russian pipelines, Moscow retains the ability to credibly sustain its opposition. Second, Azerbaijan will likely prioritize the development, production and export of its own gas reserves in addition to Shah Deniz II (Absheron, Umid and ACG ‘Deep’Fields) rather than assist in transporting Turkmen gas to Europe. Third, the Russian Federation’s support for Armenia is a ‘Sword of Damocles’ that could potentially be wielded to re-open the conflict with Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh. Even assuming that Baku would be prepared to strike a commercial agreement with the shippers of Turkmen gas, there needs to be a commercial player that is prepared to finance the construction of the Trans-Caspian pipeline (TCP). The further development of Turkmen upstream production (South Yolatan), the development and construction costs associated with the 800 km East-West pipeline across Turkmenistan and the development and construction costs of the TCP would add at least three additional projects and hence additional complexity to the Southern Gas Corridor. And, other than the Turkmen state, no private sector sponsors have yet come forward to support any of these projects.

So, as of early 2012, it seems very unlikely that Nabucco will become reality. This brings the competing downstream projects of the Southern Gas Corridor into focus. Before we look at these, however, we should say something about the timeframe for a decision on Shah Deniz II.

The Challenge in Early 2012

The Shah Deniz Field is being developed pursuant to a production sharing agreement (PSA) signed in 1999 and is, therefore, subject to a finite term ending in 2036. Even with the recent five-year extension,

| Although Gazprom claims that South Stream will not bring new volumes of gas to the EU, it still has to explain why it is prepared to significantly erode the netback value of its gas by paying for a new-build €16 billion project. |

But implementing the Southern Gas Corridor transportation line involves much more than selecting buyers and a corresponding downstream project(s). The Southern Gas Corridor is in fact a collection of separate projects that all require careful coordination and alignment. These projects include:

1. The Shah Deniz Upstream Capex (approximately $23 billion).

2. The Downstream European Projects (ranging from € 3 to 17 billion) which themselves again involve much coordination and alignment, permitting, planning and construction as well as alignment with existing transportation service operators (TSOs). What is needed are intergovernmental agreements between the transport countries, host government agreements between the transportation provider and the specific country, sufficient political support within the countries and the proven ability to handle the complicated engineering and construction processes, as well as legal permitting. Also needed, at least in some cases, is agreement on storage facilities or possible interconnectors to adjacent gas markets.

3. The expansion of the BOTAS system in Turkey (approximately € 2-4 billion). Ankara has an interest in buying and reselling gas and not necessarily in transiting gas only. Consequently, although a suite of intergovernmental and other agreements were signed on 25 October 2011 in Izmir between Turkey and Azerbaijan providing for the upgrade of the BOTAS-system, much work remains to be done to align specifications on the upgrades, investment, host government support and so on. However, recent reports out of Turkey suggest that BOTAS and SOCAR are now working on a new-build Trans-Anatolian Gas Pipeline (‘TANAP’), although details on funding remain scarce.

4. The needs of the Shah Deniz consortium for transportation capacity by the South Caucasus Pipeline (SCP) to accommodate Phase II volumes momentarily differ from the expectations of the Baku government to provide transportation capacity for additional Azeri reserves. Accordingly, there are hints that a new 56” pipeline will be built across the territory of Azerbaijan that will interconnect with the existing SCP in Georgia and will there, in turn, be expanded by adding two compressor stations, which will increase the transported volumes.

Given these complex tasks, the time for a decision on the Southern Gas Corridor is now. A concrete gas source has to find its market and there is no time to wait for other gas sources like Turkmen or Northern Iraqi gas. All this can and most certainly will be an issue later, but it cannot be a key factor in the decisions the Shah Deniz consortium and the Baku government have to take in the next few weeks.

ITGI, TAP and SEEP

|

| South Caucasus Pipeline (click to zoom out) |

The ITGI is really two projects in one: the Greek onshore section and IGI-Poseidon, the offshore leg linking the Greek Ionian coast to southern Italy. So far, these projects lack a credible solution to explain how more than 550 km of new-build onshore pipeline will be financed and made available on time to receive Shah Deniz II gas at the Turkish-Greek border and ship it to the Greek-Ionian coast. The assumption is that DESFA, the Greek state natural gas TSO, will construct the pipeline. But the Shah Deniz consortium and the Azerbaijan government will certainly closely observe the potential execution risks associated with such a solution. Moreover, the IGI-Poseidon offshore section constrains scalability and neither of the two IGI-Poseidon shareholders (DEPA and Edison) represent credible buyers or the capability to deliver the infrastructure.

The approach of the Trans-Adriatic-Pipeline (TAP) is, on the other hand, to construct and finance a new-build pipeline across the territory of Greece from Komotini (near the Turkish-Greek border) to the Albanian border, across Albania and the Adriatic Sea to Italy. In addition, the TAP shareholders are prepared to enter into a joint venture with DESFA for the Greek onshore section. Albania, which has gained a lot of stability since it became a NATO-member in 2009, has signalled that it will do its utmost to cooperate with the TAP consortium when it comes to planning and constructing the pipeline through Albania. Tirana has recognized the enormous chance of the integration into a transnational energy project of this dimension and sees the advantages of becoming an energy-hub for the Balkans, as there are concrete ideas of building an interconnector from Albania to transport gas to its Balkan neighbor countries, the Ionian-Adriatic Pipeline, thereby opening the perspective for an entirely new market. All this can be achieved because TAP’s main shareholders EON and Statoil represent some of Europe’s most experienced and capable onshore and offshore pipeline construction management and pipeline operators. With these important players and the third large shareholder, Switzerland’s energy utility EGL Group, TAP also has credible financial support behind it. Therefore TAP, not having been in the center of the debate like Nabucco, might nevertheless come out as the winner of the game.

But there is another serious bidder which, until now, is pretty much unknown to the broader public: the South-East Europe Pipeline (SEEP). The project, proposed by BP in September 2011, is the newest

| Many signs indicate that TAP and (perhaps a little later) SEEP will become the major Southern Gas Corridor pipelines |

Similar to what the TAP project offers regarding the possibility to transfer gas to other Balkan states, SEEP could also deliver gas to additional countries along the route including Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and potentially Croatia. Another advantage that SEEP shares with TAP is that both pipeline capacities can be increased by compressors from their original capacity of 10 bcm in the future. However, SEEP, unlike TAP, is for the time being more of a concept than a fully developed project proposal. Many of the details are still unclear, a detailed feasibility study has as-of-yet not been carried out and there is no concrete cost estimate on the table.

Still, even if TAP, which is much more mature than SEEP at this stage, will win the tender when the Shah Deniz consortium makes its upcoming decision, it might well be that SEEP will be awarded a contract at a later stage. With TAP and SEEP, Europe would have one route which would link Shah Deniz with Southern Europe and another that would ship the gas to Central and Eastern Europe. Moreover, both are small enough to minimize risks and flexible enough to be enlarged if demand in Europe grows and additional supply from Azerbaijan or gas resources from Iraq, Iran, Turkmenistan or even Egypt would be ready to be delivered. It will not be Nabucco, nor will it be ITGI. Many signs indicate that TAP and (perhaps a little later) SEEP will become the major Southern Gas Corridor pipelines.

What will these developments mean for the EU? On the one hand, it is obvious that Russia will remain an important energy partner for the EU. On the other, however, it is also clear that Russia alone cannot meet the EU’s need for a balanced and competitive gas market. Liquefied natural gas and supplies from other regions are becoming new alternatives for Europe and are increasingly putting pressure on oil-indexed gas prices. For European energy companies, these developments provide a positive perspective by increasing their options in terms of sourcing, duration of contracts and price. This enhances competition – and that is welcome news.

|

Who is Friedbert Pflüger? Friedbert Pflüger is Professor and Director of the European Centre for Energy and Resource Security (EUCERS) at King’s College London. He served for twenty years as a Member of Parliament and was State Secretary in the first Merkel government. Pflüger is an adivsor to the Albanian government on its gas policy. He wrote two earlier articles for EER:

|

Discussion (0 comments)