US and EU trade sanctions against Chinese solar PV cells: a blow for solar power and sustainable development

on

US and EU trade sanctions against Chinese solar PV cells: a blow for solar power and sustainable development

US and (potential) EU trade sanctions against Chinese solar panel producers will only benefit a handful of domestic panel producers, and will inflict great damage on the rest of the solar power industry in the US and EU, argues John A. Mathews, professor of global strategy at the MGSM Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia. Worse, they threaten to block the sensational cost reductions that have been going on in the global solar sector, ultimately hurting developing countries the most. "The contrast between the narrow calculations displayed in these trade actions, and the broader concerns over sustainable development and mitigation of global warming, is stark indeed", concludes Mathews.

|

| US and (potential) EU trade sanctions threaten to block the sensational cost reductions that have been going on in the global solar sector (c) sinautech.com |

On October 10 the US Department of Commerce (DoC) handed down its final ruling in the anti-dumping and countervailing duties case against Chinese solar photovoltaic (PV) cell producers, imposing tariffs of 31% and more on PV cells imported into the US and countervailing duties to match subsidies of 15%. This followed an interim ruling by the DoC in April, in the now-famous case brought by a group of US solar cell producers led by German-based SolarWorld. The finding has to be confirmed by the International Trade Commission, in November, but this is considered a formality.

So the "Great Trade War" initiated by the US against China in the field of clean technology continues. While in one set of forums dedicated to mitigating global climate change the US presses China to build its renewable energy industries, in the forums of world trade the US has brought cases against Chinese solar PV cell exporters, and wind power system exporters, seeking to curb their success.

Since China exports 80 to 90% of its solar PV cell production, with much of the output going to the US, these determinations by the DoC will hurt many of the Chinese producers who have stayed at home. But it will have no bearing on Chinese producers who have already set up manufacturing and assembly operations in the US, nor will it impact on Chinese producers who set up operations in third countries such as Taiwan.

China has fought the charges, naturally enough, and has opened up a new front through its Ministry of Commerce initiating investigations of US exports to China of solar PV manufacturing equipment and US exports of silicon ingots, the highly specialized initial product that all solar PV cell producers need.

US trade surplus

This is where the US action is likely to have a boomerang effect, hurting American firms more than Chinese. It is not widely known that the US actually runs a trade surplus with China on solar systems,

| It is not widely known that the US actually runs a trade surplus with China on solar systems, recording a surplus of $240 million in 2010 |

Now in a "normal" trade environment, this is exactly what would be predicted - in a pattern first recognized as a development trajectory by the Japanese economist Akamatsu and his famous "flying geese" model of trade adjustment. The developing country first imports products; then it starts to make the low-value products while importing the high-value components and equipment; then eventually it moves upstream to produce these for itself, and the process finishes as it moves to export these products and components - to the next developing country. China’s trajectory in solar PV cell production is an exact version of this story.

But US actions to turn clean energy into a trade war have induced the Chinese to move faster up the value chain than anticipated. Now firms like SolarTech, Yingli et al are moving to cover as many steps in the value chain as they can, while internationalizing their operations. Specialist polysilicon firms are moving to the top of the world ladder, led by China's GCL and LDK. Equipment producers are emerging, such as JYT and Jinggong. (See "Chinese PV equipment suppliers grab further market share", SolarBuzz, Jan 16 2012) China's moves to focus more on growing its domestic market rather than exports as a growth strategy will now be accelerated, giving these components and equipment suppliers a ready market in China as well as the full-fledged PV cell producers.

Indeed China's 12th Five year Plan (covering the years 2011 to 2015) sets a goal of having three to four PV equipment suppliers operating by 2015 each with annual sales exceeding RMB 10 billion, with the

| China's moves to focus more on growing its domestic market rather than exports as a growth strategy will now be accelerated |

Chinese counter-actions targeting the PV equipment and polysilicon suppliers from the US could therefore have a devastating impact on American high-tech producers. Dow-Corning CEO Robert Hansen has commented on the negative impact of the US trade action, pointing to job losses and losses of exports along the entire value chain.

Tragedy

Exactly the same arguments now apply to Europe as well. In September, the EU responded to another consortium of solar cell producers, again led by Solarworld, and announced that it would launch an investigation into Chinese solar PV cell exports to Europe. The investigation would have to be completed within nine months, and if upheld would result in the EU bringing an action against China in the WTO, as well as imposing counter-tariffs. China's polysilicon producers have launched a counter-action, and are urging the Ministry of Commerce to launch a formal investigation of European exports of polysilicon to China. As in the case of the US, European companies like Wacker Chemie, which carries most of the polysilicon trade, would be hit hardest by any Chinese counter-action.

The tragedy is that the case against Chinese exports brought by the US and EU manufacturing groups led by SolarWorld is argued solely in terms of the interests of a handful of panel producers, occupying just the middle portion of the value chain, and ignores the economic damage that will be inflicted on the large numbers employed in the upper and lower reaches of the value chain. The trade conflict ignores the wider issues (particularly the issue of global warming) and the real determinants of the Chinese trade successes.

|

|

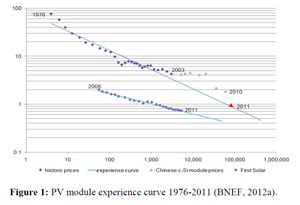

Figure 1. PV module experience curve, 1976-2011 (click to enlarge) Source: BNEF Bazilian et al (2012), Fig. 1 |

As I have argued in an earlier article (Solar panels in China: An emerging US-China trade dispute?, The Globalist, Jan 19 2012), the reason that global solar panel prices have been falling is due entirely to Chinese determination to increase the scale of mass production, driving costs down along the experience curve, and to dramatic reduction in the price of polysilicon. Consider the PV learning curve shown in Fig. 1.

In this chart, based on and updating the chart on experience curves contained in the IPCC report on Renewable Energies, the overall experience curve is shown in the upper blue line, indicating that costs had reduced to the long anticipated point of $1 per watt by the end of 2011 and bringing solar PV power within the range of almost all emerging and developing countries. The years immediately preceding this show that costs hovered for several years (2004 to 2008) at around four times this level ($4/W) - a phenomenon now understood to be due to suppliers being able to command feed-in tariff rates locked at these levels, while restricted polysilicon supplies (e.g. from the US and EU) meant that there was little price competition. It was this that led many to believe that costs of renewable energies would always exceed those of conventionally fuelled power. But as polysilicon supplies became more flexible, so manufacturers reduced their prices, which in turn reduced input costs for solar cell producers, and their prices fell as well. The message for developing countries is clear: the costs of solar PV cells are falling at around 45% per year. Solar power is becoming a viable option worldwide because of China's actions in bringing down the costs.

The bottom blue line represents the cost curve for thin-film solar cell producers, dominated by the US firm First Solar. Because thin-film PV cells utilize much lower quantities of silicon their costs have always been lower - but are not yet enjoying the economies of scale of amorphous silicon cells. (And they are excluded from the US trade action.)

Now the trade action threatens to block all these learning curve cost reductions, by raising prices for solar panels and limiting market growth. A small group of PV cell producers in the US and the EU will benefit in the short-term, while the higher value-adding producers in the US and Europe will pay heavily through China's counter-action, and consumers everywhere will lose through having to pay more for solar cell installations.

The real losers will be developing countries who will miss out on the anticipated cost reductions in solar PV systems through the deliberate interruption to the experience curve perpetrated by the DoC and (potentially) by the EU. The contrast between the narrow calculations displayed in these trade actions, and the broader concerns over sustainable development and mitigation of global warming, is stark indeed.

|

About the author John Mathews (john.mathews@mgsm.edu.au) is the Chair of Strategy at the Macquarie Graduate School of Management at Macquarie University, Sydney, and for the past three years held the Eni Chair of Competitive Dynamics and Global Strategy at the LUISS Guido Carli University in Rome.. He is a member of the Advisory Board of the Climate Bonds Initiative, London; the Jamison Group on Alternative Fuels in Australia (advisers to the National Roads and Motorists Association); the GLOBELICS network; and the Network for Sustainable Financial Markets. Professor Mathews has been a Visiting Fellow at the Rockefeller Foundation's Bellagio Study Centre, and was convenor of a Bellagio Study group on sustainable biofuels. He has consulted to the OECD, the World Bank, UNCTAD, UNIDO and the ILO on various aspects of industrial development, global dynamics and technological capabilities diffusion. His most recent books are "Strategizing, Disequilibrium and Profit" (Stanford University Press, 2006); "Dragon Multinational: A New Model of Global Growth" (Oxford University Press, 2002); and "Tiger Technology: The Creation of a Semiconductor Industry in East Asia" (Cambridge University Press, 2000). He is currently finalizing a new book on the theme of "The Next Great Transformation: The Greening of Capitalism." |

Discussion (0 comments)