Will UK competition be sacrificed at the altar of low-carbon power?

on

Will UK competition be sacrificed at the altar of low-carbon power?

Next week is the deadline for consultation on market reforms aimed at decarbonising electricity generation in the UK. The government has yet to publish the responses. But at a recent Ofgem seminar in London it was clear that the spread of views will be wide. Power company EDF Energy supports the proposals because they would create strong incentives for investment in low-carbon energy sources, such as nuclear power and renewables. But investment bank Rothschild fears they would unravel all the work of recent decades to make electricity generation competitive.

|

| Once again Britain is blazing a trail for innovative energy market reforms (photo: EDF group) |

Once again Britain is blazing a trail for innovative energy market reforms. During the 1980s and 1990s, it led the world in bringing competition into markets for natural gas and electricity. But that was during an era when climate change was not a policy priority. Today it is. So the government has been formulating policy proposals that would decarbonise electricity generation while maintaining supply security and keeping the market competitive.

This will not be an easy feat. Power companies have voiced support for the proposals. But there are some who argue that they would propel the electricity market towards a 'single-buyer' model - the kind of model that policy-makers have spent decades trying to get us away from.

Growing threat

Last December the UK government launched the consultation for its Electricity Market Reform (EMR) policy proposals. It set 10th March as the deadline for responses and promised a White Paper in late spring. Announcing the proposals in parliament, energy secretary Chris Huhne said: 'The case for reform is clear . . . As old coal and nuclear plants shut down - and demand for electricity grows - we must build the next generation of power stations . . . Without action we will face a real and growing threat to the security of our supply. The reserve margin will fall over the next decade, and the risk of interruptions to our energy supplies will rise.'

The investment challenge is huge. Over the coming decade the UK needs to replace a quarter of its power stations. At the same time 30% of the nation's electricity will need to come from renewables by 2020, up from 7% today, to meet the EU's renewable energy target. The country will also need new nuclear and gas-fired power stations, with gas-fired power playing a key role in backing up intermittent renewables. A further complication is that the government is not confident the current market will guarantee enough electricity at peak periods - because of an expected fall in the reserve margin of spare generating capacity.

£110 billion challenge

Huhne says more than £110 billion of investment in power generation capacity and grid connections is needed by 2020 - 'double the investment rate of the last decade'. And the government expects most of

| 'The UK government's two current consultations, on carbon-price floor and electricity market reform, represent precisely the sort of strategic, holistic and fair reforms needed to drive timely investment' |

- Carbon-price floor - Electricity generators have been lobbying for years for a higher and more certain carbon price than is provided by the EU's Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). The government’s response is a range of proposals from the Treasury that would create a long-term carbon-price floor (with the level rising over time). These proposals have been the subject of a separate Treasury consultation, with a deadline for responses of 11th February. Final decisions are due before the Budget, so that legislation can be introduced in the 2011 Finance Bill.

- Long-term contracts with price guarantees - To make low-carbon generation investments yet more attractive, the government is proposing long-term contracts with Feed-In Tariffs. The proposed model is a 'contract for difference' (CFD) that would top up payments when wholesale prices are low and claw back money when they are high. This would effectively give low-carbon generators guaranteed prices for their output - arguably the most controversial aspect of the proposed reforms.

- Capacity payments - To encourage the construction of reserve plants, or demand-reduction measures (so-called 'negawatts'), additional payments would be made under a proposed capacity mechanism. The objective is to ensure 'an adequate safety cushion of capacity as the amount of intermittent and inflexible low-carbon generation increases'.

- Emission performance standard - To limit the amount of carbon that the most dirty - in other words, coal-fired - power stations emit, an Emission Performance Standard would reinforce the existing requirement that no new coal plant is built without CCS technology.

'Strategic, holistic and fair'

The government has yet to publish the responses to its consultation, but a good indication of how controversial they are came in a recent Ofgem seminar, at which EDF Energy and investment bank Rothschild set out their views.

Vincent de Rivaz, chief executive of EDF Energy, the company spearheading the hoped-for nuclear power renaissance in the UK, following its takeover of nuclear generator British Energy in 2009,

| 'In fact, it may be difficult for any new generation investment to occur without one or other form of contractual protection against the market price' |

His views are of particular interest given that, along with partner Centrica, EDF Energy plans to invest 'upwards of £20 billion' on four new nuclear power stations in the UK. The first is due to come on stream in 2018. De Rivaz said that reforms would need to be delivered in 2011 to allow a final investment decision (FID) to take place next year.

'Inadvertently disruptive'

However, Huhne's assertion that 'the competitive market will remain at the centre of our energy policy' and De Rivaz's view that the reforms 'will sustain a liberalised energy market' were challenged by Stephen Vaughan, vice-chairman of European utilities at Rothschild.

Vaughan is a energy reform veteran. He has been with Rothschild since 1988. He worked on the privatisation of the UK electricity supply industry and advised British Energy on its sale to EDF - a company that is of course controlled by the French government. Describing the government's proposals as 'radical', he believes they may be 'inadvertently disruptive'. 'The ever-growing proportion of generation that's protected, either by CFDs or by the targeted capacity payments, will inevitably make that liberalised portion of the market less predictable and it will shrink,' he warned.

'In fact, it may be difficult for any new generation investment to occur without one or other form of contractual protection against the market price. As this happens, the market will evolve increasingly to look like the single-buyer model - the model that was rejected during the 1990s in favour of the liberalised market.

European impact

Vaughan noted that 'it's going to be interesting to see how the proposal, if adopted, might impact policy in other European countries. Historically the UK has been something of an evangelist for the liberalised market. This apparent reversal could prove to be a real turning point for the liberalised market across the whole of Europe. We are convinced that we shouldn't jettison the liberalised market. It's just simply addressing the wrong risk.'

|

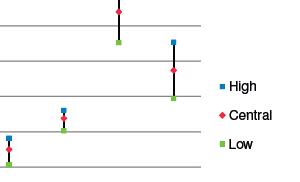

| Levelised costs of generation technologies (graphic opens in a new window) |

De Rivaz, speaking for his company which plays the leading role in marketing French nuclear energy technology to the rest of the world, regards the idea of a carbon price floor positively. He said the EU's Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) is 'a key tool in driving decarbonisation', but noted that its carbon price has been consistently below the level originally envisaged. 'With today's price at around €14/tonne of CO2 the incentive for investors to direct limited capital into low-carbon investment now is compromised,' he said. 'We firmly believe that a floor price for carbon which starts low and increases over time, when new generation comes on line, will help reinstate the anticipated price trajectory of carbon in the UK, driving investor confidence.'

To strike a fair balance for both customers and industry, he believes the floor price should follow the middle path currently proposed by the UK government, reaching £30/t of CO2 by 2020. 'The carbon floor will be vital in allowing the UK to take the steps needed to meet our share of European decarbonisation targets. In the long run we believe that the investment it will facilitate will help keep energy prices affordable, which is an issue for every EU member state.'

De Rivaz also showed himself a supporter of capacity payments. 'As we take the steps needed to meet the EU target of sourcing 15% of energy from renewable sources, so too do we need to plan for increasing intermittency on our grid created by technologies such as wind', he said. 'In rewarding such generation for its important function in maintaining security of supply, we believe these payments should be made to all plant that is ready and available at times of peak demand.'

About the proposed CFDs (long-term contracts with price guarantees), De Rivaz said that, 'through addressing risks and volatility in the marketplace, these arrangements complement carbon price and capacity reform in providing price certainty for customers and investors. They will allow investors such as us to deliver investment at the lowest possible cost whilst protecting energy users against the possibility of high gas and power prices.'

Capital constraints

Describing the long-term CFDs as 'the policy mechanism most obviously directed towards large-scale low-carbon generation projects', Vaughan agreed that 'the price certainty that this will give to all forms of low-carbon generation will probably be attractive to investors'. But in addition to pointing out the issue of how price guarantees will affect competition in generation, he questioned the availability of sufficient

| 'A carbon price floor will be vital in allowing the UK to take the steps needed to meet our share of European decarbonisation targets' |

Vaughan made a clear distinction between divisible scaleable projects, such as regulated networks and onshore wind, which he described as relatively easy to fund, and large-scale multi-billion-euro non-scalable investments, typically low-carbon projects such as offshore wind, nuclear and CCS. This latter category, he reckons, makes up about half of the investment required in the UK. He sees these large-scale generation projects as presenting the greatest challenge, because of 'the funding constraints of the large-cap companies that are the main sponsors of those projects'.

|

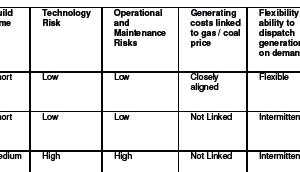

| Technology characteristics (graphic opens in a new window) |

In the longer term, it may be even more fascinating to see just how the government's determination to meet climate change targets will impact the success of its last great electricity experiment: the introduction of competition into the electricity generation market.

Discussion (0 comments)