Adaptive 3D printing

January 28, 2017

on

on

Three dimensional printing ('3D printing') enables objects to be fabricated quickly, by stacking thin layers of polymer according to an accurate pattern. Once an object is ready, the polymers from which it is built are 'dead' – meaning that it is not possible to attach new polymer chains to it.

Researchers from MIT have succeeded in developing a technique that allows objects to be printed and subsequently permit new polymers to be added, which alter the chemical composition and mechanical properties. This technique also enables two or more printed objects to be joined together in order to create more complex structures.

Back in 2013 the researchers already discovered that, when subjected to UV light, it was possible to break the polymers in defined locations, which results in extremely reactive 'free radicals'. Here it now becomes possible to join new monomers from a solution in which the object is submerged. This method is actually very difficult to control because the free radicals are really too reactive.

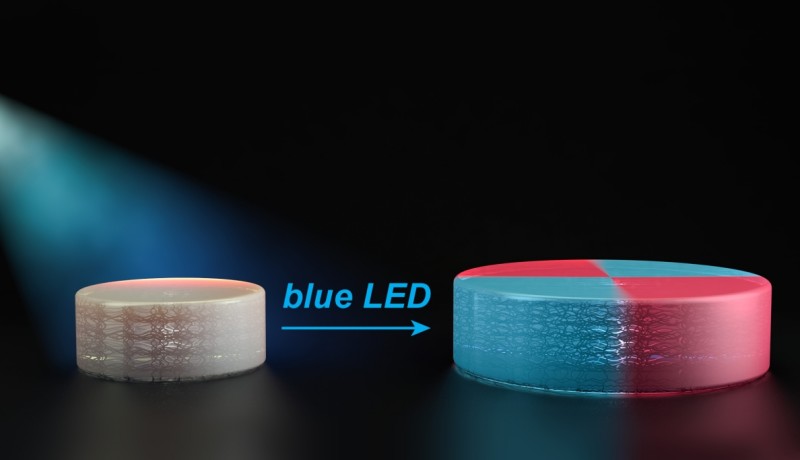

The researchers, under leadership of professor Jeremiah Johnson, have now developed polymers that react differently when under the influence of light. Each of these polymers contain chemical groups (so-called TTCs), which behave like a folded up accordion. These groups are activated by organic catalysts under the influence of blue light. These new monomers are then joined to the TTCs, which extends them. Because these monomers are incorporated uniformly into the structure, they give the material new properties.

A disadvantage of this new technique is that this process has to take place in an oxygen-free environment, for now. The researchers are however testing other catalysts which can be used in the presence of oxygen.

Researchers from MIT have succeeded in developing a technique that allows objects to be printed and subsequently permit new polymers to be added, which alter the chemical composition and mechanical properties. This technique also enables two or more printed objects to be joined together in order to create more complex structures.

Back in 2013 the researchers already discovered that, when subjected to UV light, it was possible to break the polymers in defined locations, which results in extremely reactive 'free radicals'. Here it now becomes possible to join new monomers from a solution in which the object is submerged. This method is actually very difficult to control because the free radicals are really too reactive.

The researchers, under leadership of professor Jeremiah Johnson, have now developed polymers that react differently when under the influence of light. Each of these polymers contain chemical groups (so-called TTCs), which behave like a folded up accordion. These groups are activated by organic catalysts under the influence of blue light. These new monomers are then joined to the TTCs, which extends them. Because these monomers are incorporated uniformly into the structure, they give the material new properties.

A disadvantage of this new technique is that this process has to take place in an oxygen-free environment, for now. The researchers are however testing other catalysts which can be used in the presence of oxygen.

Read full article

Hide full article

Discussion (0 comments)