Beating heart charges implanted devices

March 04, 2019

on

on

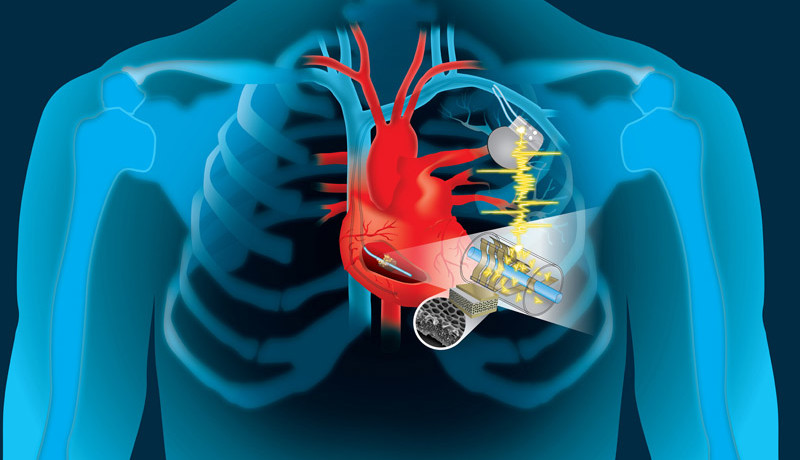

The mechanical power of the beating human heart is so strong it can be used to recharge implanted devices. Engineers at Dartmouth's Thayer School of Engineering have published a study that describes how kinetic energy produced by the beating heart can be converted into electrical energy to charge a wide range of implantable devices.

Millions of people already rely on pacemakers, defibrillators and other life-saving implants which use batteries that need replacing every five to ten years. The procedure to replace the batteries is costly and not entirely risk-free in terms of possible complications and risk of infection.

The idea they came up with is to modify pacemakers to harness the kinetic energy of the wire that connects to the heart, converting its continual rhythmic movement into electricity to charge the batteries. The material wrapped around the wire is a type of thin polymer piezoelectric film called ‘PVDF’. When this material is incorporated into porous structures — either an array of small buckle-beams or flexible cantilever transducers — it is able to convert even small mechanical movements into electricity. In addition, the electrical signals generated could be used to provide the sensor information required by the heart pace maker and enable data collection for real-time patient monitoring.

The results of this three-year study, conducted in collaboration with UT Health San Antonio clinicians, have just been published in the journal Advanced Materials Technologies.

The remaining two years of NIH funding will be used to complete the preclinical phase and obtain regulatory approval. At the moment, a commercially available fit-and-forget type pacemaker is probably still about five years down the road. A first round of testing using animals was completed with positive results.

Millions of people already rely on pacemakers, defibrillators and other life-saving implants which use batteries that need replacing every five to ten years. The procedure to replace the batteries is costly and not entirely risk-free in terms of possible complications and risk of infection.

A reliable energy source

The team set out to tap into a natural source of energy available in the body and use it to recharge implanted batteries. It goes without saying that the energy harvesting process must not impede any bodily function. The generator must also have a high level of biocompatibility, low weight, small dimensions and be flexible. On top of that, the energy source must not only be suitable to power pacemakers, but also scalable to support future multi-functionality.The idea they came up with is to modify pacemakers to harness the kinetic energy of the wire that connects to the heart, converting its continual rhythmic movement into electricity to charge the batteries. The material wrapped around the wire is a type of thin polymer piezoelectric film called ‘PVDF’. When this material is incorporated into porous structures — either an array of small buckle-beams or flexible cantilever transducers — it is able to convert even small mechanical movements into electricity. In addition, the electrical signals generated could be used to provide the sensor information required by the heart pace maker and enable data collection for real-time patient monitoring.

The results of this three-year study, conducted in collaboration with UT Health San Antonio clinicians, have just been published in the journal Advanced Materials Technologies.

The remaining two years of NIH funding will be used to complete the preclinical phase and obtain regulatory approval. At the moment, a commercially available fit-and-forget type pacemaker is probably still about five years down the road. A first round of testing using animals was completed with positive results.

Read full article

Hide full article

Discussion (0 comments)