China and the Emerging Global Energy Governance Architecture

June 30, 2015

on

on

At The Hague II Ministerial Conference on 20-21 May, China signed the International Energy Charter (IEC), joining more than 70 countries across the world in signalling their commitment to build robust energy governance architecture enabled by the declaration.

The relevance of this event can hardly be underestimated; bearing in mind the role that China plays on the global energy scene as the world’s largest energy consumer (accounting for 23% of global energy consumption), as well as the largest energy producer (accounting for 19.1% of global energy supply. [1] Last year was marked by the decline in China’s energy consumption growth, which was less than half the ten-year average (2.6% compared to 6.6%) [2] as the country’s economy has been slowing down and rebalancing away from energy intensive industries such as steal, coal and cement. China’s ‘new normal’ growth rate and energy consumption pattern is characterized by the movement towards greater efficiency and slow down in oil demand growth [3]. At the same time, we observe an increase in China’s use of natural gas and LNG, as the country aims at gradually replacing some coal and oil in its energy mix and bring natural gas at 10% of its energy consumption by 2020 [4], as well as boosting renewable energy generation. That being said, China remains to be the world’s largest growing energy market, driving the global import growth of oil and refined products. [5]

The endorsement of the IEC by a country is considered to be the first step towards signing the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT). Although it remains to be seen whether and/or under which conditions China may take this next step, the fact that it signed the IEC is a strong political signal in itself, which marks China’s engagement in the creation of global energy governance.

As the Energy Charter goes through the modernisation process (see Article 2), it currently moves to its second phase, which not only involves improving the procedures of the Energy Charter Process, but may potentially lead to negotiating the updated version of the Energy Charter Treaty in the future.

At the moment, relations with China and the Energy Charter are indeed livelier than ever. It is safe to say that the country is a very active participant in the Energy Charter Process, especially now that a new window of opportunity has opened up for shaping and influencing the future of the political framework of this international energy governance platform.

China is not new to the Energy Charter Process. Having received observer status in 2001, the country sent several of its governmental officials as secondees from the Chinese National Energy Administration to the Energy Charter Secretariat, who participate more and more actively in such Energy Charter initiatives as the Task Force for Regional Energy Cooperation in Central Asia. The latter has a particular focus on the cooperation in the region’s secure energy supply and sustainability. [6]

Last year, the Chinese energy major China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) requested membership in the Industry Advisory Panel (IAP) of the Energy Charter, and it proposed to host the next IAP meeting in Beijing in July 2015. The latter will look into the added value of the ECT in promoting energy investment projects.

When it comes to assessing the relevance of the International Energy Charter and the Energy Charter Treaty for China, several aspects of the country’s national and regional energy priorities, as well as the dynamics within the Process and the broader Energy Charter constituency have to be considered.

The holistic understanding of energy security put forward by the IEC, which encompasses security of supply, security of demand, security of energy transportation and transit, and not least, alleviation of energy poverty provides a common ground for cooperation with China, as well as the international forum for political and industry dialogue between China and such key energy partners, as the countries in Central Asia and Africa.

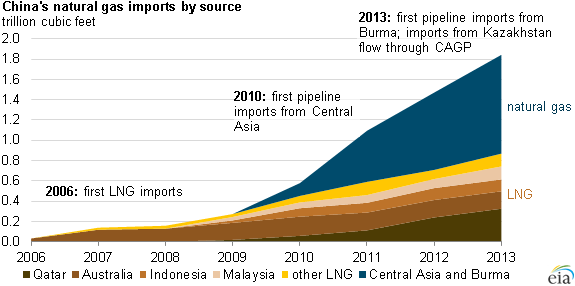

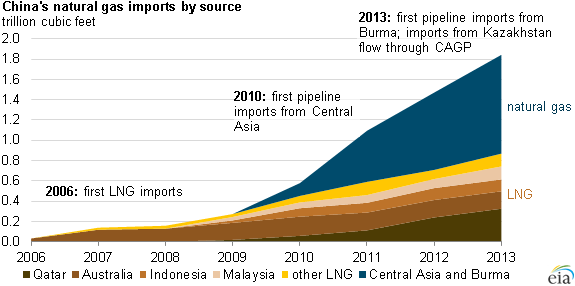

Energy cooperation between China and Central Asia clearly plays a crucial role in meeting growing Chinese energy demand, as well as the country’s ambitious goal of securing strategic petroleum reserves and crude oil storage (by 2020 China aims to build strategic crude oil storage capacity of at least 500 million barrels). When it comes to natural gas, the share of the supplies from Central Asia in Chinese imports has been substantially increasing over the last decade (Figure 1).

Figure 1. China’s Natural gas imports by source

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, International Energy Statistics

On the political level, the importance attributed to the region is reflected in the country’s ‘One Belt One Road’ initiative [7] or ‘The New Silk Road’ envisaged as a network of energy infrastructure projects (as well as rail and roads) and other infrastructure projects, stretching from Xi’an in Central China, through Central Asia and reaching Moscow, Rotterdam, and Venice.

As stated in China’s address at the Energy Charter’s Ministerial Conference in the Hague on 20 May, “the proposed ‘Silk Road Economic Belt and 21 century maritime silk road’ involves 65 countries, covering existing domain and expanding in the direction of Energy Charter. China will further develop energy communication and deepen the cooperation with member countries, observing countries and international organizations with the aid of Energy Charter.” To this end, four objectives for the multilateral and bilateral cooperation were highlighted further: “First, enhancing the pragmatic cooperation level with emerging economies. Second, [China] welcome[s] the Energy Charter to participate in the “One Belt One Road” process together with China and relevant countries. Third, [China would urge the Energy Charter to] continue pushing forward the negotiation on the energy transit issue [Transit Protocol]. Fourth, [to] enlarge the communication and cooperation with Chinese energy enterprises.”

Notably, the first countries that the leader of the People's Republic of China, Chairman Xi Jinping, visited after his inauguration were the ones in Central Asia: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

Having entered the Central Asian oil and gas sector back in 1997 with some 9 billion USD investment deal between CNPC and Kazakhstan, for the past two decades China has been actively investing in the region’s energy sector and has developed a robust network of pipelines bringing natural gas reserves from Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan (through Lines A, B, C of the Central Asian Gas Pipeline (CAGP), and Line D - currently under construction - bringing natural gas from the second stage of the Galkynysh field), as well as acquired equity in some of the upstream projects.

Both energy investments and trade relations between China and Central Asian countries have been evolving and gaining maturity, moving from the exploration and production sector to downstream and refining, pipeline operations, as well as energy production from renewable sources, developments of power grids, and uranium exploration and trade (Kazakhstan has the second largest uranium reserves in the world after Australia).

One may recall the statement of Mr Uzakabai Karabalin, First Vice Minister of Energy of Kazakhstan at the Ministerial Conference in The Hague who emphasized the importance of the Chinese endorsement of the International Energy Charter for Kazakhstan: "the fact that China has signed the International Energy Charter pleases us, as it is impossible to transfer large volumes of gas and oil between the two countries and at the same time, not to have some steering, so to say. Of course, there are bilateral and multilateral agreements, but this document [the IEC] allows us to create the basis for safe transportation and mutually beneficial energy trade." [8]

Countries in Central Asia have indeed been very much involved in the Energy Charter initiatives since its establishment in the 1990s, while Kazakhstan was the first country to take up the yearly rotating Chairmanship of the Charter in 2014 as a state (not a political representative/individual), highlighting the importance of the Energy Charter for the country’s energy policy and investments. At the same time, Kazakhstan played a prominent role in supporting the negotiations of the International Energy Charter during its presidency, and it is known that China has been playing an active role in this process as well.

It is clear that the endorsement of the International Energy Charter is beneficial for China’s energy strategy in Central Asia, and some experts would argue that acceding the Energy Charter Treaty would further facilitate security of energy transportation and trade in the region, as well as investment protection.

The spectrum of legal instruments for energy cooperation between China and the countries in the region includes Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) and Inter-Governmental Agreements (IGAs) which are often project-specific, as well as Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) - currently the key legal instruments promoting and protecting Foreign Direct Investments. There are also two international platforms in place: the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the Four Countries and Seven Partners (FCSP) coordination mechanism. [9]

The SCO was founded in 2001 by Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan and is an important initiative aiming at improving the overall security in the region and cooperation against terrorism and extremism. However, it does not have a strong energy component and does not provide any basic legally binding rules for its members.

The FCSP in turn, was established in 2010 bringing four countries-stakeholders of the Central Asian-China Gas Pipeline: China, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, as well as three joint-venture companies set up by CNPC with Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. This mechanism is very project-specific and is established to ensure the stability of pipeline operations. At the same time, yet again, it does not contain any transnational legally binding provisions.

Although expert opinions regarding the advantages of the investment protection mechanisms that are currently in place in the region over those offered by the ECT vary, some point out a number of the strengths of the Treaty’s provisions not only in protecting foreign investments and ensuring a level playing field, but also security of transit (coupled with the experience of the Charter in the Transit Protocol negotiations) and the Early Warning Mechanism. Apart from that, the conciliation mechanism for transit disputes arguably allows for a much more rapid and less formal dispute settlement compared to that in the World Trade Organisation (WTO). [10]

In the area of energy efficiency, the ECT’s Protocol on Energy Efficiency and Related Environmental Aspects (PEEREA) does not carry as much weight as the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change), however it possibly provides softer legally binding commitments. [11]

One may argue that the cooperation between China and countries in Central Asia can be the bridge to China’s greater involvement in the Energy Charter Process. According to prof. Keun-Wook Paik, Senior Fellow, Oxford Institute for Energy, the dialogue between the Energy Charter and some key planners in Beijing has to be taken forward – as prof. Paik maintains, “[I] hope ECT [Energy Charter and the Secretariat] could continue the efforts [of engaging with the key planners in China] as China's exposure on the transit pipeline will be getting bigger in line with the Central Asian Gas Pipeline's development. Eventually China will see the benefit of ECT.”

At the same time, legal experts in the field point to the fact that, in order to become truly relevant for China and bring the added value in terms of the investment protection provisions, the ECT has to be modernised and adapted to the advanced international legal practices in the domain. This way, according to prof. Wenhua Shan, Dean of the Xi’an Jiaotong University School of Law (China) and State Special Advisor [12] the ECT could become beneficial for the Chinese investors operating across the ECT member-states, however this would clearly entail a lengthy negotiation process within the ECT constituency. Another question that Prof. Shan points out has to do with the perception of the current ECT constituency towards China’s potential involvement in Energy Charter’s modernisation and its role in the global energy governance.

Clearly, the extent to which both the ECT members are ready to welcome the proactive role of China remains to be seen. The ‘European’ past of the International Energy Charter may hinder Chinese decisive involvement in the Charter Process, given the strong historical link between the Charter and Europe and the widespread understanding (even if it isn’t always objective) that it serves the interests of the European countries.

That being said, the signing of the International Energy Charter by China (in combination with the expansion of the Energy Charter’s constituency and the link between the Energy Charter‘s modernisation process and the One Road One Belt initiative put forward by China) does provide an extraordinary window of opportunity for cooperation between the two.

The upcoming meeting of the Energy Charter’s Industry Advisory Panel in July hosted by CNPC in Beijing will therefore be another milestone for Chinese involvement in the Energy Charter Process.

1. BP Statistical Review 2015, China Insights Factsheet.

2. Ibid.

3.For a detailed analysis see China: the ‘new normal’, M. Meidan, A. Sen and R. Campbell, Oxford Institute for Energy, Oxford Energy Comment.

4. China, International energy data and analysis, U.S. Energy Information Administration, 14 May 2015, p.2.

5. BP Statistical Review 2015, China Insights Factsheet.

6. international.energycharter.org.

7. The ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ and ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road’ introduced by Chinese president Xi Jinping in 2013 form the cornerstone of the country’s economic strategy and foreign policy.

8. Kazakhstan signs International Energy Charter, Kazakh TV, 22 May 2015.

9. Securing Energy Flows from Central Asia to China and the Relevance of the Energy Charter Treaty to China, Zhuwei WANG for the Energy Charter Secretariat.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Prof. Wenhua Shan is Dean of the Xi’an Jiaotong University School of Law; State Special Advisor; MOE Changjiang Chair Professor; Senior Fellow, LCIL, University of Cambridge; Editor-in-Chief, The Chinese Journal of Comparative Law (OUP).

Image: A coal shipment underway in China by Rob Loftis under CC-BY license.

The relevance of this event can hardly be underestimated; bearing in mind the role that China plays on the global energy scene as the world’s largest energy consumer (accounting for 23% of global energy consumption), as well as the largest energy producer (accounting for 19.1% of global energy supply. [1] Last year was marked by the decline in China’s energy consumption growth, which was less than half the ten-year average (2.6% compared to 6.6%) [2] as the country’s economy has been slowing down and rebalancing away from energy intensive industries such as steal, coal and cement. China’s ‘new normal’ growth rate and energy consumption pattern is characterized by the movement towards greater efficiency and slow down in oil demand growth [3]. At the same time, we observe an increase in China’s use of natural gas and LNG, as the country aims at gradually replacing some coal and oil in its energy mix and bring natural gas at 10% of its energy consumption by 2020 [4], as well as boosting renewable energy generation. That being said, China remains to be the world’s largest growing energy market, driving the global import growth of oil and refined products. [5]

The endorsement of the IEC by a country is considered to be the first step towards signing the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT). Although it remains to be seen whether and/or under which conditions China may take this next step, the fact that it signed the IEC is a strong political signal in itself, which marks China’s engagement in the creation of global energy governance.

As the Energy Charter goes through the modernisation process (see Article 2), it currently moves to its second phase, which not only involves improving the procedures of the Energy Charter Process, but may potentially lead to negotiating the updated version of the Energy Charter Treaty in the future.

At the moment, relations with China and the Energy Charter are indeed livelier than ever. It is safe to say that the country is a very active participant in the Energy Charter Process, especially now that a new window of opportunity has opened up for shaping and influencing the future of the political framework of this international energy governance platform.

China is not new to the Energy Charter Process. Having received observer status in 2001, the country sent several of its governmental officials as secondees from the Chinese National Energy Administration to the Energy Charter Secretariat, who participate more and more actively in such Energy Charter initiatives as the Task Force for Regional Energy Cooperation in Central Asia. The latter has a particular focus on the cooperation in the region’s secure energy supply and sustainability. [6]

Last year, the Chinese energy major China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) requested membership in the Industry Advisory Panel (IAP) of the Energy Charter, and it proposed to host the next IAP meeting in Beijing in July 2015. The latter will look into the added value of the ECT in promoting energy investment projects.

When it comes to assessing the relevance of the International Energy Charter and the Energy Charter Treaty for China, several aspects of the country’s national and regional energy priorities, as well as the dynamics within the Process and the broader Energy Charter constituency have to be considered.

The holistic understanding of energy security put forward by the IEC, which encompasses security of supply, security of demand, security of energy transportation and transit, and not least, alleviation of energy poverty provides a common ground for cooperation with China, as well as the international forum for political and industry dialogue between China and such key energy partners, as the countries in Central Asia and Africa.

Energy cooperation between China and Central Asia clearly plays a crucial role in meeting growing Chinese energy demand, as well as the country’s ambitious goal of securing strategic petroleum reserves and crude oil storage (by 2020 China aims to build strategic crude oil storage capacity of at least 500 million barrels). When it comes to natural gas, the share of the supplies from Central Asia in Chinese imports has been substantially increasing over the last decade (Figure 1).

Figure 1. China’s Natural gas imports by source

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, International Energy Statistics

On the political level, the importance attributed to the region is reflected in the country’s ‘One Belt One Road’ initiative [7] or ‘The New Silk Road’ envisaged as a network of energy infrastructure projects (as well as rail and roads) and other infrastructure projects, stretching from Xi’an in Central China, through Central Asia and reaching Moscow, Rotterdam, and Venice.

As stated in China’s address at the Energy Charter’s Ministerial Conference in the Hague on 20 May, “the proposed ‘Silk Road Economic Belt and 21 century maritime silk road’ involves 65 countries, covering existing domain and expanding in the direction of Energy Charter. China will further develop energy communication and deepen the cooperation with member countries, observing countries and international organizations with the aid of Energy Charter.” To this end, four objectives for the multilateral and bilateral cooperation were highlighted further: “First, enhancing the pragmatic cooperation level with emerging economies. Second, [China] welcome[s] the Energy Charter to participate in the “One Belt One Road” process together with China and relevant countries. Third, [China would urge the Energy Charter to] continue pushing forward the negotiation on the energy transit issue [Transit Protocol]. Fourth, [to] enlarge the communication and cooperation with Chinese energy enterprises.”

Notably, the first countries that the leader of the People's Republic of China, Chairman Xi Jinping, visited after his inauguration were the ones in Central Asia: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

Having entered the Central Asian oil and gas sector back in 1997 with some 9 billion USD investment deal between CNPC and Kazakhstan, for the past two decades China has been actively investing in the region’s energy sector and has developed a robust network of pipelines bringing natural gas reserves from Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan (through Lines A, B, C of the Central Asian Gas Pipeline (CAGP), and Line D - currently under construction - bringing natural gas from the second stage of the Galkynysh field), as well as acquired equity in some of the upstream projects.

Both energy investments and trade relations between China and Central Asian countries have been evolving and gaining maturity, moving from the exploration and production sector to downstream and refining, pipeline operations, as well as energy production from renewable sources, developments of power grids, and uranium exploration and trade (Kazakhstan has the second largest uranium reserves in the world after Australia).

One may recall the statement of Mr Uzakabai Karabalin, First Vice Minister of Energy of Kazakhstan at the Ministerial Conference in The Hague who emphasized the importance of the Chinese endorsement of the International Energy Charter for Kazakhstan: "the fact that China has signed the International Energy Charter pleases us, as it is impossible to transfer large volumes of gas and oil between the two countries and at the same time, not to have some steering, so to say. Of course, there are bilateral and multilateral agreements, but this document [the IEC] allows us to create the basis for safe transportation and mutually beneficial energy trade." [8]

Countries in Central Asia have indeed been very much involved in the Energy Charter initiatives since its establishment in the 1990s, while Kazakhstan was the first country to take up the yearly rotating Chairmanship of the Charter in 2014 as a state (not a political representative/individual), highlighting the importance of the Energy Charter for the country’s energy policy and investments. At the same time, Kazakhstan played a prominent role in supporting the negotiations of the International Energy Charter during its presidency, and it is known that China has been playing an active role in this process as well.

It is clear that the endorsement of the International Energy Charter is beneficial for China’s energy strategy in Central Asia, and some experts would argue that acceding the Energy Charter Treaty would further facilitate security of energy transportation and trade in the region, as well as investment protection.

The spectrum of legal instruments for energy cooperation between China and the countries in the region includes Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) and Inter-Governmental Agreements (IGAs) which are often project-specific, as well as Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) - currently the key legal instruments promoting and protecting Foreign Direct Investments. There are also two international platforms in place: the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the Four Countries and Seven Partners (FCSP) coordination mechanism. [9]

The SCO was founded in 2001 by Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan and is an important initiative aiming at improving the overall security in the region and cooperation against terrorism and extremism. However, it does not have a strong energy component and does not provide any basic legally binding rules for its members.

The FCSP in turn, was established in 2010 bringing four countries-stakeholders of the Central Asian-China Gas Pipeline: China, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, as well as three joint-venture companies set up by CNPC with Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. This mechanism is very project-specific and is established to ensure the stability of pipeline operations. At the same time, yet again, it does not contain any transnational legally binding provisions.

Although expert opinions regarding the advantages of the investment protection mechanisms that are currently in place in the region over those offered by the ECT vary, some point out a number of the strengths of the Treaty’s provisions not only in protecting foreign investments and ensuring a level playing field, but also security of transit (coupled with the experience of the Charter in the Transit Protocol negotiations) and the Early Warning Mechanism. Apart from that, the conciliation mechanism for transit disputes arguably allows for a much more rapid and less formal dispute settlement compared to that in the World Trade Organisation (WTO). [10]

In the area of energy efficiency, the ECT’s Protocol on Energy Efficiency and Related Environmental Aspects (PEEREA) does not carry as much weight as the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change), however it possibly provides softer legally binding commitments. [11]

One may argue that the cooperation between China and countries in Central Asia can be the bridge to China’s greater involvement in the Energy Charter Process. According to prof. Keun-Wook Paik, Senior Fellow, Oxford Institute for Energy, the dialogue between the Energy Charter and some key planners in Beijing has to be taken forward – as prof. Paik maintains, “[I] hope ECT [Energy Charter and the Secretariat] could continue the efforts [of engaging with the key planners in China] as China's exposure on the transit pipeline will be getting bigger in line with the Central Asian Gas Pipeline's development. Eventually China will see the benefit of ECT.”

At the same time, legal experts in the field point to the fact that, in order to become truly relevant for China and bring the added value in terms of the investment protection provisions, the ECT has to be modernised and adapted to the advanced international legal practices in the domain. This way, according to prof. Wenhua Shan, Dean of the Xi’an Jiaotong University School of Law (China) and State Special Advisor [12] the ECT could become beneficial for the Chinese investors operating across the ECT member-states, however this would clearly entail a lengthy negotiation process within the ECT constituency. Another question that Prof. Shan points out has to do with the perception of the current ECT constituency towards China’s potential involvement in Energy Charter’s modernisation and its role in the global energy governance.

Clearly, the extent to which both the ECT members are ready to welcome the proactive role of China remains to be seen. The ‘European’ past of the International Energy Charter may hinder Chinese decisive involvement in the Charter Process, given the strong historical link between the Charter and Europe and the widespread understanding (even if it isn’t always objective) that it serves the interests of the European countries.

That being said, the signing of the International Energy Charter by China (in combination with the expansion of the Energy Charter’s constituency and the link between the Energy Charter‘s modernisation process and the One Road One Belt initiative put forward by China) does provide an extraordinary window of opportunity for cooperation between the two.

The upcoming meeting of the Energy Charter’s Industry Advisory Panel in July hosted by CNPC in Beijing will therefore be another milestone for Chinese involvement in the Energy Charter Process.

1. BP Statistical Review 2015, China Insights Factsheet.

2. Ibid.

3.For a detailed analysis see China: the ‘new normal’, M. Meidan, A. Sen and R. Campbell, Oxford Institute for Energy, Oxford Energy Comment.

4. China, International energy data and analysis, U.S. Energy Information Administration, 14 May 2015, p.2.

5. BP Statistical Review 2015, China Insights Factsheet.

6. international.energycharter.org.

7. The ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ and ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road’ introduced by Chinese president Xi Jinping in 2013 form the cornerstone of the country’s economic strategy and foreign policy.

8. Kazakhstan signs International Energy Charter, Kazakh TV, 22 May 2015.

9. Securing Energy Flows from Central Asia to China and the Relevance of the Energy Charter Treaty to China, Zhuwei WANG for the Energy Charter Secretariat.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Prof. Wenhua Shan is Dean of the Xi’an Jiaotong University School of Law; State Special Advisor; MOE Changjiang Chair Professor; Senior Fellow, LCIL, University of Cambridge; Editor-in-Chief, The Chinese Journal of Comparative Law (OUP).

Image: A coal shipment underway in China by Rob Loftis under CC-BY license.

The Energy Charter Secretariat monitors the implementation of the 1994 Energy Charter Treaty and provides support to the Treaty-based international organisation, the Energy Charter Conference (52 states and the EU and EURATOM). The Treaty strengthens the rule of law on energy issues, by creating a level playing field of rules to be observed by all participating governments, thereby mitigating risks associated with energy-related investment and trade. The Treaty focuses on: the protection of foreign investments; non-discriminatory conditions for energy trade; reliable energy transit; the resolution of state-to-state and, in the case of investments, investor-state disputes; and energy efficiency policies.

The International Energy Charter is a political declaration to be adopted in The Hague on 20 May 2015. It is designed to spread fundamental principles of international energy cooperation to new partner countries.

This series of materials is part of a wider awareness-raising campaign aimed at promoting the renewed role and creating further momentum behind the Energy Charter in today’s global energy markets.

Read full article

Hide full article

Discussion (0 comments)