Foldable array of solar cells printed on a sheet of paper

on

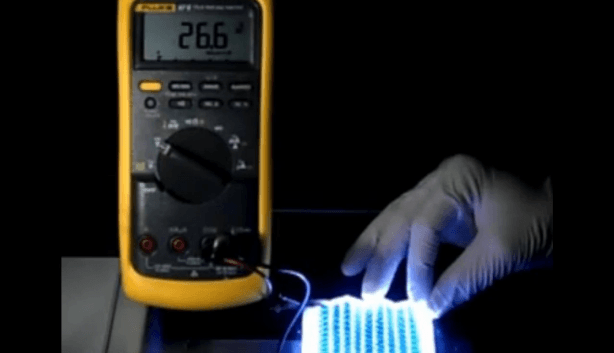

The sheet of paper looks like any other document that might have just come spitting out of an office printer, with an array of colored rectangles printed over much of its surface. But then a researcher picks it up, clips a couple of wires to one end, and shines a light on the paper. Instantly an LCD clock display at the other end of the wires starts to display the time.

Almost as cheaply and easily as printing a photo on your inkjet, an inexpensive, simple solar cell has been created on that flimsy sheet, formed from special “inks” deposited on the paper. You can even fold it up to slip into a pocket, then unfold it and watch it generating electricity again in the sunlight.

The new technology, developed by a team of researchers at MIT, is reported in a paper in the journal Advanced Materials, published online July 8. The technique represents a major departure from the systems used until now to create most solar cells, which require exposing the substrates to potentially damaging conditions, either in the form of liquids or high temperatures. The new printing process uses vapors, not liquids, and temperatures less than 120 degrees Celsius. These “gentle” conditions make it possible to use ordinary untreated paper, cloth or plastic as the substrate on which the solar cells can be printed.

It is, to be sure, a bit more complex than just printing out a term paper. In order to create an array of photovoltaic cells on the paper, five layers of material need to be deposited onto the same sheet of paper in successive passes, using a mask (also made of paper) to form the patterns of cells on the surface. And the process has to take place in a vacuum chamber.

The basic process is essentially the same as the one used to make the silvery lining in your bag of potato chips: a vapor-deposition process that can be carried out inexpensively on a vast commercial scale.

The resilient solar cells still function even when folded up into a paper airplane. In their paper, the MIT researchers also describe printing a solar cell on a sheet of PET plastic (a thinner version of the material used for soda bottles) and then folding and unfolding it 1,000 times, with no significant loss of performance. By contrast, a commercially produced solar cell on the same material failed after a single folding.

For outdoor uses, the researchers demonstrated that the paper could be coated with standard lamination materials, to protect it from the elements.

Others have tried to produce solar cells and other electronic components on paper, but the big stumbling block has been paper’s rough, fibrous surface at a microscopic scale. To counter that, past attempts have relied on coating the paper first with some smooth material. But in this research, ordinary, uncoated paper was used — including printer paper, tissue, tracing paper and even newsprint with the printing still on it. All of these worked just fine.

The researchers continue to work on improving the devices. At present, the paper-printed solar cells have an efficiency of about 1 percent, but the team believes this can be increased significantly with further fine-tuning of the materials. But even at the present level, “it’s good enough to power a small electric gizmo,

Source: MIT news

Discussion (0 comments)