Impact of VW Scandal on the Energy Sector

October 28, 2015

on

on

While there has been much discussion about the impact of the VW diesel scandal on the car industry, there has been little attention paid to its impact on the energy sector. At this point, with VW the leading diesel car manufacturer globally, it already looks like diesel may not be as feasible a route to lower carbon dioxide emissions as had been thought, and more so if other manufacturers are also found to have manipulated emissions test results. This means much of the excise and taxation designed to favour diesel in Europe could well be reversed, which will encourage the use of other fuels such as gasoline and natural gas (CNG and LNG) in transportation, as well as electric and hybrid vehicles.

To meet the change in demand towards gasoline, Europe’s refiners would require an expensive reconfiguration of capacity to favour a lighter gasoline-focused yield. Europe had been moving towards cleaner emissions using standards applied both to diesel quality and engine performance, with the two progressing in tandem. The purification of diesel fuel to the low sulphur levels required (Euro 5, or 0.01%) has already cost the refining industry billions to install expensive desulphurisation equipment. A fall in European demand could undermine this investment.

Similarly, billions of dollars have been spent on refineries designed to export Euro grade diesel to Europe from the Middle East and elsewhere. In the last year or two, more than 1.2 million b/d of refining capacity has been put into operation in the Middle East, with a further 2.2 million b/d by 2020, according to Enerdata. Most of this will be up to Euro-5 standard products, targeting Europe as part of attempts to add value to oil exports. US supply too, had been expected to continue to slip across the Atlantic in greater quantities – pushed out if its home market by increased LNG use and rising unconventional crude production and refining.

Speaking recently on the BBC, ex BP chief executive, John Browne, said: “This crisis has opened up questions about diesel itself, which will create a very difficult situation for the oil industry … If they have to produce more gasoline they will be able to, but it could create some interesting pricing problems.” He added that a switch to gasoline would take time and would be likely to increase refining costs. “Gasoline prices would certainly be likely to rise relative to diesel,” he said, which would alter refinery economics and undermine the investment that had been made to produce clean European diesel grades.

For the last 14 years wholesale diesel prices have stood at a premium to gasoline in Europe due to its popularity as a transportation fuel, causing refiners to concentrate on maximising its output. But recently, slowing demand and increased diesel imports have meant gasoline has resumed its traditional top spot as the crude cut of choice. The VW news is likely to further undermine diesel’s relative value to both gasoline and crude feedstock. There may also be an impact on the relative price of different crude oil streams, with those rich in middle distillates losing value relative to those with high gasoline content.

Clamour is already growing for favourable taxes applied to diesel to be removed. In the UK, Stephen Tindale, ex head of Greenpeace and advisor to Tony Blair’s government at the time favourable diesel taxes were introduced, acknowledged in early October that the policy had been flawed, and worse still, was possibly “responsible for many deaths”. The additional mileage possible using diesel engines may have cut the carbon dioxide per mile, but it incurred a whole host of additional pollutants, he added.

However with the future of Europe’s refining sector possibly at stake, Lord Browne urged caution: “We need to stop overly rapid regulation; we need to think carefully about diesel itself - it may be right to reduce use; it may not be.”

More significantly perhaps, the scandal has shone a light on the trade-off between fuel economy, performance and particulate emissions, and has highlighted the limits to further improvement in combustion engines generally. If emissions cannot be reduced by increasing fossil fuel efficiency (if it is at the expense of air quality), then alternatives must be found to both diesel and gasoline. Several leading car makers have already said they are switching research and investment to electric and hybrid engines - including VW itself - in their efforts to reduce emissions from the transport sector and improve performance.

VW said in early October that it would move investment to electric and hybrid cars in Europe, a move that is partly intended to improve public image, and reverse some of the damage done from the diesel emissions. "We are becoming more efficient, we are giving our product range and our core technologies a new focus, and we are creating room for forward-looking technologies by speeding up the efficiency programme," said VW's Dr Herbert Diess. It also revealed that its flagship Phaeton model would in the future be purely electric, capable of driving long distances on a single charge.

Regulators and consumers too, may follow suit. In the UK, the Institute of the Motor Industry (IMI) has found 53% of drivers planning to buy or lease a car in the next two years are looking at electric or hybrid vehicles as their next car. This compares to the 56,000 electric and hybrid cars sold so far this year, which represented only 3% of all new car registrations – illustrating the rapid rise in interest.

Cheaper gas as a result of fracking is also challenging diesel as a transport fuel, and this could be extended by the VW scandal. In October, Shell announced the opening of its third Liquefied Natural Gas truck refuelling station in the Netherlands. The new station has a capacity of 70,000 liters/day, enough to fuel around 200 trucks daily, and may be the beginning of the sort of transition to LNG seen among heavy goods vehicles in North America.

Such moves could see demand for refined products – gasoline as well as diesel – fall much more sharply than expected, especially in interventionist states such as the EU, causing a more rapid move to game-changing technology and a more fundamental upheaval in the energy sector than otherwise.

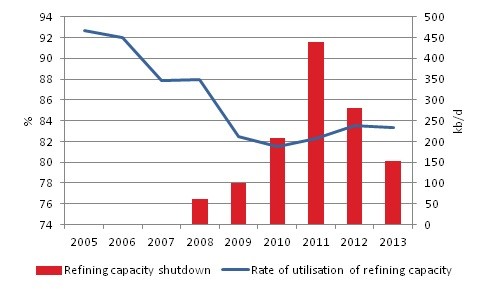

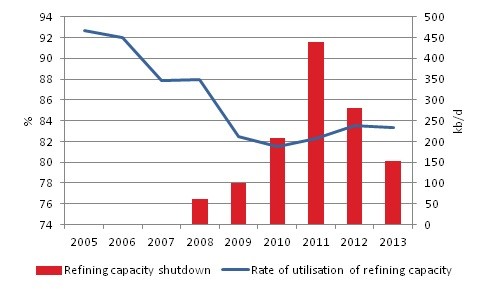

Table 1: European refinery run rates and closures

Source: Enerdata

Europe’s refining sector has already seen multiple closures over recent years as demand has slowly edged down (see Table 1). And even before the scandal broke, surging imports and falling demand had already led analysts to forecast the closure of at least ten more European refineries by 2018, on top of the 1.2 million b/d that closed recently.

All Europe’s largest refiners, including shell, Total and Eni, had already been looking to sell or adapt plants to lower petroleum product demand, which has declined by more than 18% since 2006, according to Enerdata – although crude price falls had produced a slight recovery in demand this year as drivers responded to lower prices. The fall-out from the VW diesel scandal could accelerate the long term downward trend, leading to the winding up of many refineries more quickly across the continent.

All this represents a major challenge for Europe’s oil and gas companies, which still supply the bulk of Europe’s energy needs, and will be expected to efficiently meet the demands of European citizens for whichever combination of fuels and electric they move towards.

Shell, Total and other major European oil companies contacted declined to comment on the issue.

To meet the change in demand towards gasoline, Europe’s refiners would require an expensive reconfiguration of capacity to favour a lighter gasoline-focused yield. Europe had been moving towards cleaner emissions using standards applied both to diesel quality and engine performance, with the two progressing in tandem. The purification of diesel fuel to the low sulphur levels required (Euro 5, or 0.01%) has already cost the refining industry billions to install expensive desulphurisation equipment. A fall in European demand could undermine this investment.

Similarly, billions of dollars have been spent on refineries designed to export Euro grade diesel to Europe from the Middle East and elsewhere. In the last year or two, more than 1.2 million b/d of refining capacity has been put into operation in the Middle East, with a further 2.2 million b/d by 2020, according to Enerdata. Most of this will be up to Euro-5 standard products, targeting Europe as part of attempts to add value to oil exports. US supply too, had been expected to continue to slip across the Atlantic in greater quantities – pushed out if its home market by increased LNG use and rising unconventional crude production and refining.

Speaking recently on the BBC, ex BP chief executive, John Browne, said: “This crisis has opened up questions about diesel itself, which will create a very difficult situation for the oil industry … If they have to produce more gasoline they will be able to, but it could create some interesting pricing problems.” He added that a switch to gasoline would take time and would be likely to increase refining costs. “Gasoline prices would certainly be likely to rise relative to diesel,” he said, which would alter refinery economics and undermine the investment that had been made to produce clean European diesel grades.

For the last 14 years wholesale diesel prices have stood at a premium to gasoline in Europe due to its popularity as a transportation fuel, causing refiners to concentrate on maximising its output. But recently, slowing demand and increased diesel imports have meant gasoline has resumed its traditional top spot as the crude cut of choice. The VW news is likely to further undermine diesel’s relative value to both gasoline and crude feedstock. There may also be an impact on the relative price of different crude oil streams, with those rich in middle distillates losing value relative to those with high gasoline content.

Rising unpopularity

Clamour is already growing for favourable taxes applied to diesel to be removed. In the UK, Stephen Tindale, ex head of Greenpeace and advisor to Tony Blair’s government at the time favourable diesel taxes were introduced, acknowledged in early October that the policy had been flawed, and worse still, was possibly “responsible for many deaths”. The additional mileage possible using diesel engines may have cut the carbon dioxide per mile, but it incurred a whole host of additional pollutants, he added.

However with the future of Europe’s refining sector possibly at stake, Lord Browne urged caution: “We need to stop overly rapid regulation; we need to think carefully about diesel itself - it may be right to reduce use; it may not be.”

Limits to combustion

More significantly perhaps, the scandal has shone a light on the trade-off between fuel economy, performance and particulate emissions, and has highlighted the limits to further improvement in combustion engines generally. If emissions cannot be reduced by increasing fossil fuel efficiency (if it is at the expense of air quality), then alternatives must be found to both diesel and gasoline. Several leading car makers have already said they are switching research and investment to electric and hybrid engines - including VW itself - in their efforts to reduce emissions from the transport sector and improve performance.

VW said in early October that it would move investment to electric and hybrid cars in Europe, a move that is partly intended to improve public image, and reverse some of the damage done from the diesel emissions. "We are becoming more efficient, we are giving our product range and our core technologies a new focus, and we are creating room for forward-looking technologies by speeding up the efficiency programme," said VW's Dr Herbert Diess. It also revealed that its flagship Phaeton model would in the future be purely electric, capable of driving long distances on a single charge.

Regulators and consumers too, may follow suit. In the UK, the Institute of the Motor Industry (IMI) has found 53% of drivers planning to buy or lease a car in the next two years are looking at electric or hybrid vehicles as their next car. This compares to the 56,000 electric and hybrid cars sold so far this year, which represented only 3% of all new car registrations – illustrating the rapid rise in interest.

Cheaper gas as a result of fracking is also challenging diesel as a transport fuel, and this could be extended by the VW scandal. In October, Shell announced the opening of its third Liquefied Natural Gas truck refuelling station in the Netherlands. The new station has a capacity of 70,000 liters/day, enough to fuel around 200 trucks daily, and may be the beginning of the sort of transition to LNG seen among heavy goods vehicles in North America.

Such moves could see demand for refined products – gasoline as well as diesel – fall much more sharply than expected, especially in interventionist states such as the EU, causing a more rapid move to game-changing technology and a more fundamental upheaval in the energy sector than otherwise.

Table 1: European refinery run rates and closures

Source: Enerdata

End of an era?

Europe’s refining sector has already seen multiple closures over recent years as demand has slowly edged down (see Table 1). And even before the scandal broke, surging imports and falling demand had already led analysts to forecast the closure of at least ten more European refineries by 2018, on top of the 1.2 million b/d that closed recently.

All Europe’s largest refiners, including shell, Total and Eni, had already been looking to sell or adapt plants to lower petroleum product demand, which has declined by more than 18% since 2006, according to Enerdata – although crude price falls had produced a slight recovery in demand this year as drivers responded to lower prices. The fall-out from the VW diesel scandal could accelerate the long term downward trend, leading to the winding up of many refineries more quickly across the continent.

All this represents a major challenge for Europe’s oil and gas companies, which still supply the bulk of Europe’s energy needs, and will be expected to efficiently meet the demands of European citizens for whichever combination of fuels and electric they move towards.

Shell, Total and other major European oil companies contacted declined to comment on the issue.

Read full article

Hide full article

Discussion (0 comments)