The Real Risks of Artificial Intelligence

December 08, 2015

on

on

If you’ve paid attention to just about any media outlet lately, you’ve likely seen the dire warnings about the threat to humanity posed by artificial intelligence that have been issued by the likes of Elon Musk, Bill Gates and Stephen Hawking. However, according to four artificial intelligence researchers that I’ve interviewed in the past three months, while AI’s risks may be cause for concern, shaping our AI future may have more to do with directing current trends, rather than overtly preventing “Terminators.”

As a long-time artificial intelligence researcher and scholar, RPI professor James Hendler brings a realist’s view to the discussion of AI risks. While he does see the potential dangers of autonomous weapons, Hendler believes the larger issue in artificial intelligence is in perception and policy.

"It's interesting being an old timer in AI, because when I was getting into the field, all the critiques were saying, ‘This stuff is impossible! It's never gonna’ work! Why are you wasting your time?’ Now, all of a sudden in the last few years, it’s shifted to ‘Hey this stuff is starting to work, we’re scared,’” he said. “This brings up all the fears of science fiction.”

Those fears, Hendler believes, are being driven by the fact that some things that were once considered science fiction, such as speech recognition and self-driving cars, are now becoming a reality. And, in Hendler’s eyes, it’s that uncertainty of what might come next that’s fueling the fear of AI.

“Hawking takes that a step further and says ‘When machines start self replicating and evolving on their own, won't they fill the niche better than we will?’” Hendler said. “That’s seems to me to be a sort of odd question to be asking these days. It’s hard to be the guy taking the nuanced view of things, robot apocalypse or robots are the savior, but I think there’s a lot of space in the middle, and that’s where we are today.”

One possibility of a machine filling a human niche that does concern Hendler is the risk posed by autonomous weapons. The key to minimizing that risk, he said, is to insure humans stay in control of the decision-making process.

“Weapons, that's a real concern. That's really not so much because we're worried about AI becoming super intelligent, but because we're worried about computers being put in places where human judgement is still really needed,” Hendler said. “Computers are good at some things and humans are good at other things, and when we don’t take that into account, and we make policies without thinking about them, that could get us into trouble.”

Physicist and author Louis Del Monte was inspired to write his book, The Artificial Intelligence Revolution, after reviewing a 2009 Swiss Institute of Technology for Intelligent Systems study, which programmed robots to cooperate with each other in the search for food. The test found some robots were more successful than others at finding food; after about 50 generations of improvement in the machines, the robots stopped cooperating entirely and refused to share the food they’d found. That development of a sense of self-preservation shaped Del Monte’s views on the future of artificial intelligence.

“When I went through that experiment, I became concerned that a strong artificially intelligent machine (SAM) could have a mindset of its own and its agenda may not align with our agenda,” he said. “The concern I had was, will it serve us or replace us?”

Del Monte noted that, currently, the belief is machines are serving us. However, things may change as artificial intelligence continues to advance and the change, he said, may come sooner than anticipated.

“I predict that between 2025 and 2030, machines will be as advanced as the human mind and will be equivalent to the human body,” Del Monte said. “Between 2040 and 2045, we will have developed a machine or machines that are not only equivalent to a human mind, but more intelligent than the entire human race combined.”

Though rooted in science fiction, Del Monte believes Isaac Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics may provide the solution. That solution, he believes, lies not in software, but in hardware. Some have argued as to whether hard-wired approaches could genuinely steer AI in a human-friendly direction, it’s an idea that may have a chance to prove its merit in the coming decades.

“We take Asimov’s laws, and whatever we in humanity think is important, we put it in hardware, not software. It would be integrated circuits… solid state circuits that would act as filters to make sure a machine is doing no harm,” he said. “I’m not saying we should halt AI or limit intelligence. We should just insure there is hardware technology in the machine that limits its capability to harm humanity.”

Neuroscientist and Artificial Intelligence Expert Dr. Danko Nikolic argues that artificial intelligence is still essentially in an embryonic state. Further, he believes that even with the ability to manipulate the machine genome to speed up the evolutionary process, a robot that would be a danger to society would be unlikely.

"Our biological children are born with a set of knowledge. They know where to learn, they know where to pay attention. Robots simply can not do that,” Nikolic said. “The problem is you can not program it. There's a trick we can use called AI kindergarten. Then we can basically interact with this robot kind of like we do with children in kindergarten, but then make robots learn one level lower...at the level of something called machine genome.”

Nikolic compares the manipulation of that genome to the selective breeding that ultimately evolved ferocious wolves into friendly dogs. The results of robotic evolution will be equally benign and, he believes, any attempts to develop so-called “killer robots” won’t happen overnight. Just as it takes roughly 20 years for a child to fully develop into an adult, Nikolic sees an equally long process for artificial intelligence to evolve.

“People's opinions depend very much on what they think AI is about and how they see AI developing. If you look at similar attempts in the past where we manipulated the genome of biological systems, it turns out what it produced was very benign,” Nikolic said. “I don’t foresee us creating something overtly dangerous (with robots). If AI develops off of a core genome… then we can’t change the genome of a machine or of a biological system by just changing a few parts. What we will end up with, I believe, will be a very friendly AI that will care for humans and serve humans, and that’s all we will ever use.”

According to artificial general intelligence researcher and Temple University Professor Dr. Pei Wang, the safety of AI will only be as good as its development. While he can certainly foresee the risks of artificial intelligence, that doesn’t mean its development should be halted.

“AI is dangerous. This is true for any major technical breakthrough and there is no purely benign technology,” he said. “Some people claim we should slow down the development of AI. They say it’s the only way we can make sure it will be safe. But actually, it's the other way around.”

The possible consequences need to be considered; but those who want to design AI with the false assumption that it will be safe don’t have a thorough understanding of artificial intelligence, Wang said. To illustrate his point, he cited the example of a married couple’s plans for their future child and how their views change when faced with the reality of actually raising a child.

“AI might initially be a lot more like a baby when it starts off. Every baby has the potential to be a good guy or a bad guy,” he said. “The difference is not in the initial design, it mostly comes from education. Design is neutral with respect to this topic.”

While he’s adamant that slowing the development of artificial intelligence won’t enhance its safety, Wang also believes the extent of that research is being overstated. The reality, he said, comes back to understanding.

“Our current development is much slower than most people outside the field might believe. AI research is still in its very early stage,” Wang said. “Almost everyone working in the field believes we can develop something comparable to human intelligence. Contrary to what a lot of people believe, we still have a long way to go.”

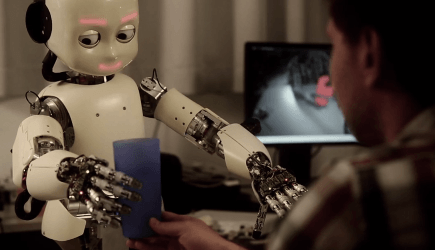

Image: The iCub humanoid robot at IDSIA's robotics lab in Switzerland trying to reach for a blue cup. To do so it has to plan and control the movement of all its joints in unison. By Juxi. CC-BY license.

Facts versus fiction

As a long-time artificial intelligence researcher and scholar, RPI professor James Hendler brings a realist’s view to the discussion of AI risks. While he does see the potential dangers of autonomous weapons, Hendler believes the larger issue in artificial intelligence is in perception and policy.

"It's interesting being an old timer in AI, because when I was getting into the field, all the critiques were saying, ‘This stuff is impossible! It's never gonna’ work! Why are you wasting your time?’ Now, all of a sudden in the last few years, it’s shifted to ‘Hey this stuff is starting to work, we’re scared,’” he said. “This brings up all the fears of science fiction.”

Those fears, Hendler believes, are being driven by the fact that some things that were once considered science fiction, such as speech recognition and self-driving cars, are now becoming a reality. And, in Hendler’s eyes, it’s that uncertainty of what might come next that’s fueling the fear of AI.

“Hawking takes that a step further and says ‘When machines start self replicating and evolving on their own, won't they fill the niche better than we will?’” Hendler said. “That’s seems to me to be a sort of odd question to be asking these days. It’s hard to be the guy taking the nuanced view of things, robot apocalypse or robots are the savior, but I think there’s a lot of space in the middle, and that’s where we are today.”

One possibility of a machine filling a human niche that does concern Hendler is the risk posed by autonomous weapons. The key to minimizing that risk, he said, is to insure humans stay in control of the decision-making process.

“Weapons, that's a real concern. That's really not so much because we're worried about AI becoming super intelligent, but because we're worried about computers being put in places where human judgement is still really needed,” Hendler said. “Computers are good at some things and humans are good at other things, and when we don’t take that into account, and we make policies without thinking about them, that could get us into trouble.”

Hardware versus software

Physicist and author Louis Del Monte was inspired to write his book, The Artificial Intelligence Revolution, after reviewing a 2009 Swiss Institute of Technology for Intelligent Systems study, which programmed robots to cooperate with each other in the search for food. The test found some robots were more successful than others at finding food; after about 50 generations of improvement in the machines, the robots stopped cooperating entirely and refused to share the food they’d found. That development of a sense of self-preservation shaped Del Monte’s views on the future of artificial intelligence.

“When I went through that experiment, I became concerned that a strong artificially intelligent machine (SAM) could have a mindset of its own and its agenda may not align with our agenda,” he said. “The concern I had was, will it serve us or replace us?”

Del Monte noted that, currently, the belief is machines are serving us. However, things may change as artificial intelligence continues to advance and the change, he said, may come sooner than anticipated.

“I predict that between 2025 and 2030, machines will be as advanced as the human mind and will be equivalent to the human body,” Del Monte said. “Between 2040 and 2045, we will have developed a machine or machines that are not only equivalent to a human mind, but more intelligent than the entire human race combined.”

Though rooted in science fiction, Del Monte believes Isaac Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics may provide the solution. That solution, he believes, lies not in software, but in hardware. Some have argued as to whether hard-wired approaches could genuinely steer AI in a human-friendly direction, it’s an idea that may have a chance to prove its merit in the coming decades.

“We take Asimov’s laws, and whatever we in humanity think is important, we put it in hardware, not software. It would be integrated circuits… solid state circuits that would act as filters to make sure a machine is doing no harm,” he said. “I’m not saying we should halt AI or limit intelligence. We should just insure there is hardware technology in the machine that limits its capability to harm humanity.”

Education versus evolution

Neuroscientist and Artificial Intelligence Expert Dr. Danko Nikolic argues that artificial intelligence is still essentially in an embryonic state. Further, he believes that even with the ability to manipulate the machine genome to speed up the evolutionary process, a robot that would be a danger to society would be unlikely.

"Our biological children are born with a set of knowledge. They know where to learn, they know where to pay attention. Robots simply can not do that,” Nikolic said. “The problem is you can not program it. There's a trick we can use called AI kindergarten. Then we can basically interact with this robot kind of like we do with children in kindergarten, but then make robots learn one level lower...at the level of something called machine genome.”

Nikolic compares the manipulation of that genome to the selective breeding that ultimately evolved ferocious wolves into friendly dogs. The results of robotic evolution will be equally benign and, he believes, any attempts to develop so-called “killer robots” won’t happen overnight. Just as it takes roughly 20 years for a child to fully develop into an adult, Nikolic sees an equally long process for artificial intelligence to evolve.

“People's opinions depend very much on what they think AI is about and how they see AI developing. If you look at similar attempts in the past where we manipulated the genome of biological systems, it turns out what it produced was very benign,” Nikolic said. “I don’t foresee us creating something overtly dangerous (with robots). If AI develops off of a core genome… then we can’t change the genome of a machine or of a biological system by just changing a few parts. What we will end up with, I believe, will be a very friendly AI that will care for humans and serve humans, and that’s all we will ever use.”

Nature versus nurture

According to artificial general intelligence researcher and Temple University Professor Dr. Pei Wang, the safety of AI will only be as good as its development. While he can certainly foresee the risks of artificial intelligence, that doesn’t mean its development should be halted.

“AI is dangerous. This is true for any major technical breakthrough and there is no purely benign technology,” he said. “Some people claim we should slow down the development of AI. They say it’s the only way we can make sure it will be safe. But actually, it's the other way around.”

The possible consequences need to be considered; but those who want to design AI with the false assumption that it will be safe don’t have a thorough understanding of artificial intelligence, Wang said. To illustrate his point, he cited the example of a married couple’s plans for their future child and how their views change when faced with the reality of actually raising a child.

“AI might initially be a lot more like a baby when it starts off. Every baby has the potential to be a good guy or a bad guy,” he said. “The difference is not in the initial design, it mostly comes from education. Design is neutral with respect to this topic.”

While he’s adamant that slowing the development of artificial intelligence won’t enhance its safety, Wang also believes the extent of that research is being overstated. The reality, he said, comes back to understanding.

“Our current development is much slower than most people outside the field might believe. AI research is still in its very early stage,” Wang said. “Almost everyone working in the field believes we can develop something comparable to human intelligence. Contrary to what a lot of people believe, we still have a long way to go.”

Image: The iCub humanoid robot at IDSIA's robotics lab in Switzerland trying to reach for a blue cup. To do so it has to plan and control the movement of all its joints in unison. By Juxi. CC-BY license.

Read full article

Hide full article

Discussion (2 comments)