The political perils of low oil prices

on

The political perils of low oil prices

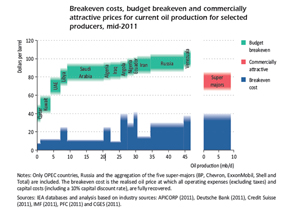

Oil prices have rapidly dropped in recent months, and some analysts predict a further (steep) decline. This might seem like good news to consumer states, but there is a catch. Whereas producer states could balance their budgets at $30 a barrel less than ten years ago, they now need $100 a barrel to make ends meet. If oil prices continue to correct, expect instability to hit producer states across the board. That might (ironically) help to set a price floor and push prices up again, but it's not a development that consumer countries should be happy about. Keeping oil prices at $100/b remains a better plan than seeing producer states collapse.

|

| Worker at an oil rig in Saudi Arabia (c) The Telegraph |

A not so silent war is being waged in the oil world right now. Prices have tumbled 31% since March which means someone needs to set a price floor, and do so fast. Most OPEC states had hoped that was going to happen when the cartel recently met in Vienna. But official quota levels were kept at 30 million barrels per day (mb/d), with the implicit agreement that once delegates flew out of Schwechat Airport, Saudi Arabia would start closing the taps to bring OPEC's non-official 31.8 mb/d production in line with the formal target. Saudi swing, Riyadh ropes.

Fair enough, but what everyone wanted to know, and especially Iran, Venezuela, and Algeria, was how far and how fast Saudi was going to make cuts and 'balance' the market. With Brent prices regularly dipping well below $100 and WTI prices considerably lower, OPEC hawks are getting very nervous. Non-OPEC producers in Russia and Central Asia even more so. Assuming demand side dynamics don't drastically pick up in Asia, we can expect three things to sequentially happen.

- The first is an international price war across all producer states to force Saudi Arabia to take assertive action to tighten the taps and raise prices. That will be a difficult process given Riyadh has its own strategic objectives to want a sustained period of moderate prices, well below $100/b.

- Secondly, if petro-hawks lose this price war, their political bluster will subside, and a far 'cruder' trend will emerge. They will have to cut back on domestic spending, which is bound to lead to a new round of protests, and more importantly sharpened domestic repression.

- Given repression is no longer the 'effective' tool it once was for producer states, that could well lead us to a third, and far more daunting prospect: any price floor will be set by producer states folding under the weight of political pressure when new crises hit. The flat price of crude will be influenced more by political unrest clipping production than by active supply restraint.

Whether that's a good path for the 'global energy system' to tread is highly unlikely.

The starting point: pricing peril

Current spot prices may be worrisome for producer states, but the real issue is how long prices will remain depressed. On the face of it, OPEC has never had it so good. Brent prices averaged historic highs of $114/b from January to June. The problem is that OPEC states have gotten used to high prices. Unless average prices continue to hold up over $100/b, financing gaps will start to show - even at benchmarks around the $80-90/b mark. That's a staggering indictment of how badly resource rich states have managed their wealth over the past few years. '$100/b' is the new '$30/b' from the early 2000s required to keep producer states in the political black.

Iran, Russia and Venezuela have their budgetary books balanced at over $110/b break even points. Ecuador has its budget balanced at three figures, with Bolivia, Argentina and Mexico in similarly precarious positions. Nigeria, Angola and Algeria are no different across Africa. Caspian States are all 'out of the money' at anything less than the $100/b mark, while Libya and Iraq need all the receipts they can muster to rebuild their shattered states. But what's perhaps even worse for producer states, is the enormous uncertainty reflected on the future curve. Under a 'business as usual' scenario, this increasingly looks like a geo-economic car crash waiting to happen.

The usual response when things get tough is to look towards the Gulf States, and in particular, Saudi Arabia, to cut supplies. That’s what happened in 2009. Riyadh clipped its production by up to 35%, complemented by a massive $2 trillion demand side stimulus in China to get the global economy going. The confidence trick worked; a widely proclaimed commodity 'super-cycle' was instantly back, traders went long on oil - culminating in price spikes of $128/b in March 2012.

True, they had no lack of supply side outages to support such a position, but the nagging demand side doubts never really went away. Now the froth has once again evaporated from the oil market cappuccino due to even deeper demand side problems. The parallels with 2008 are pretty plain to see. We've had a booming commodity market in the midst of financial and economic meltdown. But unlike 2008 when it was assumed that sovereign balance sheets could support private sector calamities, things are so much worse this time around, precisely because it's the solvency of Central Banks that the markets are directly testing. There is no lender of last resort and no safety net to fall back on.

The Eurozone is broken, the US is (ironically) rebuilding its economy on its own energy boom, whatever excess cash Middle East sovereign wealth funds once had, is now staying at home. But the market that has oil traders most worried is China. Bottom line, the vital physical 'Chirabia' relationship that worked so well for producers in 2009 simply isn't going to be reproduced on the same scale in 2012. Despite

| The vital physical 'Chirabia' relationship that worked so well for producers in 2009 simply isn't going to be reproduced on the same scale in 2012 |

Scene one: Saudi power plays

More importantly on the supply side of the equation, even with inventories bloated across international ports, Saudi Arabia has no short term interest in slashing production, for several reasons. From an ‘altruistic’ perspective, cheaper oil is giving consumer nations a useful economic boost, and central banks more room to print money without inflationary headaches. Europe's oil import bill was around $27 billion in June compared to $32 billion in March, with very similar corrections seen in the US. Fiscal pressures will also ease for emerging markets heavily subsidising fuel consumption. As long as Riyadh keeps oil at reasonable prices, global demand destruction might just be averted.

But it's the 'selfish' motives that are far more compelling for Saudi Arabia. Riyadh netted over $155 billion in the first half of 2012, and is believed to have built up $500 billion in cash reserves to alleviate domestic pressures. The al-Saud can afford a sustained period of prices around $75-80/b without being worried. What Riyadh can't make on price, it can easily make up for on volume given it will continue to pump over 9.5 mb/d. That will win Saudi Arabia considerable plaudits across consumer states, but also leaves them with total control over the remaining producer states. For all the bluster of OPEC hawks, none of them would be willing to make cuts, and all of them would continue to cheat on quotas wherever possible. It's free-riding 101, and entirely at Saudi expense.

The Kingdom isn't going to let the 'free-lunch' brigade enjoy that luxury. It's more than happy to see Iran squirm under the weight of US sanctions to re-think its nuclear posture. It also makes no bones about wresting back political influence in Lebanon, Iraq and the Gaza strip from the Persian Gulf to the Levant, not to mention clipping Shia influence in Sunni political strongholds. Internecine wars are being fought with Arab Nationalist Republics accordingly.

Further afield, nobody is too bothered about a bullish Venezuela talking up its reserves, but Riyadh considers Russia to be another petro-state that needs putting in its place. Moscow has been a real

| Moscow has been a real thorn in Saudi Arabia's Middle East side, by offering diplomatic support to Iran and military hardware to Syria |

That's the final string to Saudi Arabia's 'pricing bow' - lower prices aren't just about showing fellow petro-states who's boss, but about fighting Riyadh's bigger battle over the next decade: retaining 40% of OPEC market share in the midst of supposedly huge non-OPEC unconventional supply growth.

At $100/b prices, unconventional plays ranging from Russian extremes, to US shale oil, Canadian tar, Australian coal seams, and Brazilian pre-salt all looked highly attractive prospects. Once prices are back to $90/b the profits look thin - at $80/b marginal, at $75/b, few investors would be willing to go near that kind of risk over long and arduous project cycles. US shale becomes too dirty, Canadian tar distinctly sticky, Brazilian pre-salt horribly deep, Russian Arctic plays simply impossible. Even conventional developments could see investments eased. Hence, the al-Saud's more intricate price point is one that gives the global economy some breathing space, Riyadh the upper geopolitical hand over all petro-states, and scrubs unconventional plays off global balance sheets.

This policy might be good for OPEC's long term health, but it's a bitter (some might say lethal) pill for some members of the cartel to currently swallow. Expect them to fight tooth and nail (within and beyond) the cartel to try and get Saudi Arabia to budge and drive prices up through 'tough talking' and political bluster. Dragging Saudi Arabia back for emergency meetings in Vienna will be the first prelude to a full scale price war with the al-Saud. Iran has already tabled exactly that proposition.

But as desperate as all this sounds for petro-hawks, they still have some light at the end of the Saudi tunnel. Even Riyadh needs to increase prices to around $98/b over the next few years to finance $129 billion social spending reducing its room for pricing manoeuvre. More importantly, it also needs to consider the proximate position of its fellow GCC states. Qatar can go lower than anyone at $58/b, Kuwait is likely to find life very difficult at anything less than $85/b while the UAE needs to take a serious look at its budgets given they are currently balanced at $107/b in Abu Dhabi. The Kingdom will tread carefully to make sure such states aren't hung out to dry (for too long), especially with the Arab Awakening still very much a going concern. Defending price bands closer to $90/b than $80/b would be welcome news across the Gulf.

So as temping as a full scale pricing war might be for Saudi Arabia to make Iran, Russia et al bleed, Riyadh won't want to use GCC states as collateral damage. 'Cash rich' is a relative term these days, even for the Gulf States when it comes to trimming budgets and cutting spending.

Scene two: load the pistols

This last point ties into a far broader debate as to how far Saudi Arabia will be able to control prices if the global economy continues to tank - some would say it's already a bit like Icarus, flying too close to the sun by not defending a $100/b price band. Citigroup and Credit Suisse think prices will get significantly lower (perhaps even to $50/b into the third quarter) irrespective of OPEC actions. That clearly remains to be seen, but the fact we’re already having such a detailed discussion about seemingly trivial numbers between $100/b vs. $85/b as the new floor, is precisely because things are on such a knife edge for producer states. Small economic margins will have dramatic political effects.

|

| Breakeven costs, budget breakeven and commercially attractive prices for current oil production for selected producers, mid-2011 (click to enlarge) |

The key lesson most petro-states took from the Arab uprising is make sure you've paid off the right institutions to cover your back. Beyond the obvious ploy of tightening his grip over the resource sector, President Putin has already passed a law 'banning' protests; Algeria purged its state oil company; the 'Nasty Stans' across Central Asia pushed through snap elections, with Kazakhstan taking majority control of any new pipeline developments. Hugo Chavez is pulling out all the stops for a 'lifelong' Presidency in Venezuela. If Iran can't galvanise broad based support through its nuclear programme, it has no problem quelling the streets of Tehran by whatever means necessary. In the Gulf, Saudi Arabia made clear that revolution wasn't going to work in Bahrain; Kuwait proved very effective in drowning domestic dissent; the UAE drafted in a private military company for 'counterterrorism' and internal security purposes, just in case their own soldiers refused to open fire. And even where recent elections have taken place, the underlying role of the military remains an omnipotent presence, be it in Egypt, Nigeria or Indonesia. The tighter budgets get, the more likely it is these types of coping mechanisms kick in. Military hardware remains (in some cases) the first, but in all cases, the last line of resort.

Scene three: war and mayhem

As unedifying as all that might be, the bigger problem producer states have is that internal repression has no guarantee of success these days. It didn't work for Gadhafi in Libya, and it's unlikely to work for Assad in Syria in the long term. As fierce as the rear-guard battles have been, they’ve not been militarily conclusive or conducive to on-going hydrocarbon production.

Follow that argument through and it is clear that if the bulk of producer regimes were struggling to hang on in a $125/b world, they stand little chance of pulling through in an $80/b (or less) environment. So we reach the third step, and logical conclusion of our argument. The lower prices go, the more likely political unrest creates serious supply disruptions affecting physical supplies, with concomitant effects on paper markets. That obviously puts a radically new spin on what 'cyclical' means as far as price and political instability is concerned, but when we look across producer states, it’s hard to find any major players not sitting on a powder keg of political risk these days.

More likely than not, it will be some of the smaller players that get caught in the cross fire first. In the Gulf, Saudi Arabia is already deeply concerned about Bahrain relative to its Eastern Province. State implosion in Yemen is seen as an internal issue of the al-Saud to deal with, while serious deterioration

| More likely than not, it will be some of the smaller players that get caught in the cross fire first |

Go further up the producer state 'food chain', and some of the world's largest players all have the same structural political problems, be it in the Middle East, Eurasia or Latin America. Any sign that a bigger petro-beast is losing control, and prices would rapidly lift. That might be welcome news for producer states lucky enough to ride the price wave and remain intact, but it's a very dangerous game to play.

And that's the whole problem here - the gap between geological costs of production and the geopolitical cost of survival is simply too wide for producers to cover without falling back on draconian measures. If this 'self-correcting' mechanism between price and political unrest starts supporting an informal price floor then so be it, but we shouldn't be fooled that this is serving anyone's interests - on either side of the consumer-producer ledger. Yes, it will help firm prices when certain producers struggle to adapt to rapidly shifting economic conditions, but assuming that more and more producer states hit political problems as prices slip, we're merely cementing the 'too big to fail' status of the very largest oil producers. Seeing petro-states dropping like political flies as prices correct isn't a proper 'solution' for a floor, not only because prices will rebound with a vengeance when markets tighten, but because it will make us even more dependent on a handful of key suppliers. As we all know from previous problems in Iraq (2.9 mb/d), Iran (3 mb/d), Libya (1.48 m/bd), Nigeria (2.4 mb/d) and even Venezuela (2.7 mb/d), once things go politically wrong, it takes a very long time, if ever, to get back to optimal production levels. It's the antithesis of where consumers want to be in terms of sourcing plentiful and fungible supplies.

Final scene: corpses all over the stage

By way of reminder, as much as petro-states currently face a systemic crisis trying to set a price floor, it was only in March that we saw how badly placed OPEC is to moderate the market at the top. Seeing petro-states in a pickle might warm the hearts of many right now, but markets can turn, and turn fast. When they do, the oil weapon will shift target as well. It will no longer be pointed at petro players heads, but directly at consumer states. That's the consequence of a dysfunctional energy system - not just with a $50-$150/b outlook eminently possible, but swings well beyond that 'price band' all too likely.

Splitting this price directly in two and sticking close to $100/b might not be that bad an idea after all: Mopping up the mess from producer state implosion would require an effort far beyond the international systems capabilities and reach. Carefully agreed truces are always better than outright wars, particularly for those squeamish about collateral damage. Corpses would litter the entire energy stage.

Discussion (0 comments)