Turbulent times for European gas market

on

Turbulent times for European gas market

Europe’s natural gas industry is undergoing a revolution. Tough new competition legislation is forcing gas companies to restructure their businesses and make room for new entrants. Demand and supply uncertainties – in the form of increased import dependency, new security of supply legislation, economic crisis and a surge in unconventional gas production – have multiplied. At the same time, it remains unclear whether the European Union’s climate change policies will stimulate or dampen demand for gas. The great challenge for Europe’s gas companies will be to navigate these multiple uncertainties while taking advantage of the opportunities.

|

| Will the European Union's climate change policies stimulate or dampen demand for gas? |

In July 2009 the European Commission imposed fines of €553 million each on E.ON and GDF Suez for ‘market sharing in the French and German gas markets’. The scale of the punishment was evidence of the frustration that the Commission was feeling about the slow pace of market liberalisation and of its determination to get its way. Announcing the decision, the then Competition Commissioner, Neelie Kroes, said: ‘These are the first commission fines imposed for an anti-trust infringement in the energy sector and send a strong signal to energy incumbents that the commission will not tolerate any form of anti-competitive behaviour.’

Further evidence of this determination came in the summer of 2009 when the European Union (EU) adopted a ‘third package’ of legislation that the commission believes will succeed where two previous legislative packages have failed. It must be transposed into national law in all member states by March 2011. As a consequence, Europe’s big gas companies – who in the past have proved to be adept at foot-dragging – have been busy preparing for what will be a much tougher regulatory regime. They appear to sense that the time has come to get to grips with the rules and play the game to their best advantage.

Multiplying uncertainties

But market liberalisation and competition are not the EU’s only energy priorities. A number of other factors are causing uncertainties in the gas market.

- Security of energy supply has been a major concern ever since the energy crises of the 1970s. This concern was ramped up at the start of 2009 when yet another dispute between Russia and Ukraine led to unprecedented interruption in Russian gas supply to Europe. So the European Union’s gas companies, and indeed its member states, also have to contend with a new security of gas supply regulation which is likely to be law before the end of the year, replacing a directive in force since 2004.

- Adding yet another layer of complexity and uncertainty, the European Union sees itself as a world leader in efforts to mitigate climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. That too has major implications for energy policy in general, and natural gas policy in particular. Whether this will reduce demand for gas or increase it will depend on specific policy measures. These are likely to vary from one member state to another.

- The global recession that began in 2008 has had a major impact on gas market dynamics around the world. Demand in Europe plummeted in 2009 and it remains to be seen how quickly it will recover.

- The shale gas revolution in North America has unexpectedly pushed the United States to the top of the gas producers’ league – and pushed large volumes of LNG previously targeted at the US into other markets.

- Meanwhile, a ‘tsunami of LNG’ from projects sanctioned during 2003-2005 has contributed to the emerging global gas glut. One consequence has been a wide divergence of traded gas prices and oil prices that is putting pressure on one of the foundations of the gas industry – the traditional long-term, oil-indexed, take-or-pay gas sales contract.

Double dip

In its May 2010 Long-Term Outlook for Gas Demand and Supply, Eurogas – a trade association representing the views of several major European gas companies – announced that ‘After years of almost uninterrupted growth, the European gas industry for the first time faced severe sales losses last year.’ EU gas demand in 2009 was down 6.4% on 2008.

The outlook for the future will depend in part how quickly gas demand recovers after the steep falls of 2009. The latest reports suggest that demand is bouncing back more strongly and quickly than many expected. However, there are some who believe that we could be entering the second dip of a double-dip recession.

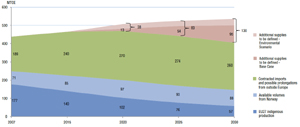

The opinion of the Eurogas Forecasting Task Force is that it will take several years before gas demand reaches the highs recorded in previous years: ‘As a result of the economic crisis and the action taken in the meantime to reach EU targets, expectations concerning the long-term development of gas demand are now some 15-20% lower than three years ago.’ Nevertheless, the Task Force added, ‘natural gas

|

| EU supply outlook (click for larger image) Source: Eurogas |

The ‘unprecedented uncertainty’ in the energy market will be a key theme of the World Energy Outlook to be published by the International Energy Agency next month. In a glimpse of what the new WEO will say, the IEA’s chief economist Fatih Birol recently said: ‘Some economists say the recovery will take a long time. Some say we will see a second recession. And some say that we will soon see a strong rebound.’ That does not make for a comfortable investment environment. And it applies especially to OECD economies, not least Europe.

Climate targets

Another source of demand uncertainty stems from climate policy. Natural gas could end up having to play a much bigger role in meeting Europe’s energy demand than many now expect, because it emits much less CO2 than coal or oil per unit of energy produced. The Copenhagen climate change talks in December 2009 came as a big disappointment to those who hoped to see a signed treaty to replace the Kyoto Protocol when it expires in 2012. But that does not mean that Europe has given up on the challenging targets it has set itself to reduce its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, to boost the share of renewables in energy supply, and to increase energy efficiency.

Indeed, some member states want to see the ‘20% cut by 2020’ target for GHG reductions increased to 30%, despite the lack of a global climate change agreement. That would put significant upward pressure on carbon prices in the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), the third phase of which will run from 2013 to 2020. Whether gas would win or lose in this scenario remains a matter of much debate.

The European Union’s ambitious targets for mitigating climate change – specifically the targets set for 2020, just a decade away – are unlikely to be achieved by means of low/zero-carbon energy sources alone. Greater use of renewables, new nuclear power stations, and clean-coal technology employing carbon capture and storage are unlikely to make the kind of difference that policy-makers anticipate in such a short timeframe. For now, policy-makers are tending to overlook natural gas in favour of renewables, nuclear electricity and ‘clean’ coal. But their attitudes could well change as it becomes clear just how difficult it will be to meet the targets without using a lot more gas.

Sufficient and secure?

Security of supply, long at the centre of European energy policy, has risen even higher up the agenda since the January 2009 dispute between Ukraine and Russia, which led to an unprecedented interruption in supply of Russian gas to several European markets.

These concerns have not been diminished by glut, nor by last year’s decline in demand. The EU authorities have been encouraging the development of a ‘fourth corridor’ of gas supply that could bring pipeline gas from the Middle East and the Caspian regions. The Commission and various national authorities have also shown a willingness to grant derogations from third-party access requirements for new infrastructure seen as helping to boost supply security.

Many believe LNG will play an increasingly important role in diversifying Europe’s gas import portfolio, not least because it can provide supply to new entrants to the market who are having trouble sourcing gas from the incumbents. As for unconventional gas, such as shale gas, there are hopes that Europe may be able to at least partly replicate the US production boom. Again shale gas could provide new supply more readily available to new market entrants. That said, these are still very early days. There are many potential obstacles in Europe, leading some to believe that shale gas will not make any appreciable impact on European gas dynamics for a decade or even two. A crucial message from the doubters is that Europe is not the United States.

In 2009, the European Commission proposed a new regulation focusing on both preventive actions and preparations for crisis management so as to be able to act efficiently and in a coordinated manner across the EU in cases of crisis and disruption of supply. It would also establish an infrastructure standard, a supply standard and reverse-flow mechanisms – and repeal the security of gas directive adopted in 2004. The regulation has been passed by the European parliament and is expected to become law before the end of the year.

EU EU |

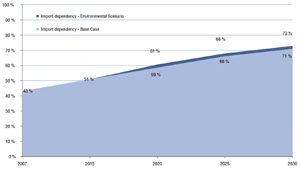

| EU import dependency (click for larger image) Source: Eurogas |

That, in itself, is not necessarily a problem. Most EU countries have little gas production of their own and so are used to depending on external suppliers, either from within the EU, or, increasingly, from outside. The major external suppliers of pipeline gas are Russia, Norway and Algeria. LNG supplies come from a wide variety of sources, because of the inherent physical flexibility of ship-borne cargoes. Suppliers include Qatar, Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Trinidad, Nigeria and Norway – amongst others. Most EU countries with a coastline either already have LNG regasification infrastructure or are building or planning to build some.

But will sufficient gas be available in the future? This is not a straightforward question. Supplies from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region are a source that many are looking to. But most suppliers in that region are already heavily committed and are seeing their own demand rise sharply. In the Gulf region, only Qatar has gas to spare, and it has imposed a moratorium on new production projects. Iran, despite having the world’s second-largest proved reserves of natural gas, is a net gas importer and its net imports are likely to grow in the short to medium term. Iraq could become a big gas exporter but, for now, it needs gas itself to overcome electricity generation shortfalls.

In North Africa, Egypt has a moratorium on new exports and could become a net importer within a decade. Algeria is struggling to meet its export target. And Libyan exploration – in the wake of the scramble for assets that took place after the lifting of sanctions in 2003/2004 – has yet to yield more than modest discoveries.

There are question marks, also, over gas supplies from the Caspian region. Azerbaijan will increase supplies with phase 2 of Shah Deniz, but Turkmenistan is looking eastwards towards China. Besides, gas from Turkmenistan would require either a trans-Caspian pipeline or transit through Iran or Russia. All three options present difficulties.

Pricing and contracts – evolution and revolution

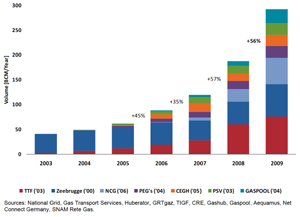

Most natural gas in Europe is still traded at the wholesale level by the incumbent monopoly suppliers under long-term, take-or-pay contracts, with prices mostly indexed to oil and oil products. However, the amount of gas traded at market hubs has been rising exponentially. Pricing on hubs is based on the supply and demand situation on each traded market. This kind of trading is potentially more accessible to new market entrants. To begin with, hub trading was slow to develop, but the view of the European Commission is that future development of traded wholesale markets is crucial for market integration and competition.

|

| Trading at Europe's gas hubs Source: IEA |

Gas buyers are caught between long-term contractual obligations and pressure from their customers, especially industrial customers, to supply gas at more competitive prices. Some buyers have even gone as far as asking for re-negotiation of their contract price formula. Importers have in turn pressed their suppliers for more flexibility on price and volumes. Some sellers, who retained their long-term oil-linked gas prices, have suffered from a lack of competitiveness in some markets and consequently have lost market share.

The IEA notes that ‘adjustments of long-term oil-based contracts have already occurred. Surprisingly, Gazprom agreed, publicly, to some concessions on both volume and price with some of its major consumers, including Eni and E.ON Ruhrgas. Gazprom and E.ON Ruhrgas agreed on linking 15% of the volumes to spot prices for a three-year period. GasTerra made it known in the 2009 negotiations concerning the extension of long-term contracts with GDF Suez, Distrigas and Swissgas, that partial

| In North Africa, Egypt has a moratorium on new exports and could become a net importer within a decade. Algeria is struggling to meet its export target |

The latest medium-term oil price scenarios from the IEA indicate that oil prices are expected to remain robust, or even exceed the current $65-85$/barrel price band. In other words, the divergence between oil and traded gas prices is likely to persist, at least for the coming half decade.

The new age of regulation

Regulation plays a central role in the development of the EU’s natural gas and electricity industries. However, the last set of directives and regulations aimed at liberalising and introducing more competition into Europe’s energy markets – adopted as long ago as 2003 – has not produced the kind of results that the European Commission was hoping for. The latest ones, in the Commission’s Third Energy Package, have certainly been concentrating minds in the industry.

As a whole, Europe has well-developed pipeline and LNG regasification infrastructure. In theory, with carefully targeted investment, it should be possible to get the European natural gas market to function as a single entity, especially within the 27 states that make up the European Union (EU). But that is not how the picture looks today.

With few exceptions, the EU’s gas markets remain largely separate from each other and are illiquid. The level of cross-border interconnection remains far from adequate and interoperability of different national networks, or rather the lack of it, remains a major issue.

Even where transportation and storage structure is adequate, there is the issue of whether third-parties – meaning potential new entrants to the market – are able to gain access to it. The issue of third-party access (TPA) on reasonable and non-discriminatory terms has been at the centre of EU legislation aiming to create a ‘Single Energy Market’. Without access to enabling infrastructure, aspiring new entrants are shut out, making the development of competition difficult, if not impossible.

There is also the issue of whether potential new entrants can gain access to supplies of natural gas, whether produced indigenously or imported by pipeline or in the form of LNG from outside the EU. In the case of LNG, imports can only work if access is available to the necessary infrastructure. Often, it isn’t.

The Third Energy Package – consisting of a directive and a regulation for electricity, a directive and a regulation for gas, and a regulation establishing a pan-European Agency for the Co-operation of Energy Regulators (ACER) – sets out to remedy the deficiencies by setting the following objectives:

- the effective separation of supply and production activities from network operation;

- the further harmonization of the powers and enhanced independence of the national energy regulators;

- the establishment of an independent mechanism for co-operation among national regulators;

- the creation of a mechanism for transmission system operators to improve the coordination of networks operation and grid security, cross-border trade and grid operation; and

- greater transparency in energy market operations.

EER recently asked Lord John Mogg – chairman of British energy regulator Ofgem, and chair of the board of ACER (the European Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators) – whether he thought the Third Energy Package would be sufficient to create a single gas market in the European Union. He replied: ‘I’m confident it will be achieved. It’s a matter of timing.’

| The divergence between oil and traded gas prices is likely to persist, at least for the coming half decade |

‘The thrust is towards integration politically as well. Particularly in gas – given the nature of gas rather than electricity – you will see a much greater integration. I would hesitate to put timelines on it. But it’s not over the horizon. It’s very much on the agenda.’

‘Nothing succeeds like success. The more people see the greater integration – the fact that there is the third package, the fact that independent regulators are genuinely collaborating, and bringing benchmarked performance – will itself make a genuine improvement in the process.’

Asked what the ACER could add to what the national regulators can do, Mogg replied: ‘It will add a formal body that will have a dedicated staff, within a year, of some 50 people, under a director who has a European face, a forward-looking attitude, that will develop policy. Secondly, the agency itself has powers, particularly in disputes between two or more regulators.’

‘My own experience from many other sectors is that once you provide an institution which brings a European dimension, policies tend to develop around it. So I wouldn’t be at all surprised if, in a decade or so, the agency gets more powers, more strength, and greater development.’

Policy matters

So what we can say about how the future is likely to look for Europe’s gas companies? Recession-induced demand collapse looks likely to be short-lived. The current gas glut, and consequent low spot gas price, will not last forever. Today's LNG tsunami is the result of projects sanctioned in 2003-2005;

| The biggest long-term challenges for Europe’s gas industry centre around issues of policy |

The biggest long-term challenges for Europe’s gas industry probably centre around issues of policy, especially when it comes to new investment in energy infrastructure. The scenarios that have been presented by organisations such as the IEA and Eurogas for the development of gas demand in Europe are highly sensitive to the policy assumptions on which they are based.

Clearly, the seismic changes under way in the gas industry are creating challenges – but change almost always creates the potential for new opportunity. For Europe’s gas industry, these are demanding but also interesting times. For the foreseeable future, there will be a high degree of uncertainty – and it is pointless to pretend there is certainty where none exists. Inevitably there will be winners and losers as companies are forced to take risks.

| On 15-16 February 2011, The European Gas Market Summit 2011 will focus on the challenges and opportunities in the new European gas market landscape. With speakers from the European Commission, the Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER), Shell, Wood Mackenzie and others. More information: http://www.eyeforenergy.com/gasmarkets/ |

Discussion (0 comments)