"The energy system moves slowly – but it does move"

on

Christof Rühl, Group Chief Economist of BP, unveils the hidden forces that steer the global energy market to a new future

"The energy system moves slowly – but it does move"

Speaking with Christof Rühl, Group Chief Economist of BP, is like getting a unique tour through the past, present – and future – of the global energy world. Rühl has a crucial – and inspiring – story to tell about how market forces, even though they are sometimes deeply buried beneath stormy state interventions, slowly but surely steer the Ship of Energy to new and undiscovered lands. EER's editor Karel Beckman spoke with Rühl about what our energy future holds in store: about the tremendous importance of technological innovation in the fossil fuel industry, which most outside observers completely miss; about what role renewables could play, if they were harnessed by market forces; about the far-reaching changes taking place in the global gas sector, which are primarily a result of liberalization and competition; about the evolving roles of national and international oil companies and governments who are all tugging at the energy beast. "It may be a slow-moving beast", Rühl says about the global energy system, "but it does move."

|

| Christof Rühl - Group Chief Economist of BP (c) bp.com |

The first BP Energy Outlook was produced in 2009, as an internal document, to provide input into the company's strategic and commercial decisions, and also to provide better alignment across the many market analyses that were floating around the company, as Rühl puts it. Three years ago, BP decided to make the Outlook public – just as it has been doing with the famous BP Statistical Review of Energy since 1952 (!) – because the British company wanted its data to "feed into the public energy debate".

"I can't think of a sector that is so important to everything we do and where the gap between its importance and the need for information is so large", says Rühl. He adds that "there are probably more economists researching happiness than energy. On energy anybody seems to be allowed to say anything."

The Chief Economist, who is also Vice-President at BP, notes that the BP Energy Outlook is fully transparent. "The underlying data are available on the internet, from 1965 on. You can walk up and down the time series and plug in your own numbers for the future if you don't agree with ours. That's the kind of debate we want. We want to provide fact-based input into the global debate. That also explains why the Outlook has this slightly nerdy format. It is an energy forecast, not a corporate brochure."

By politicians for politicians

For the same reason, says Rühl, the Outlook is a "point forecast", i.e. a projection of where the trends in the energy markets are likely taking us, unlike the IEA and Shell's outlooks, which are written as scenarios. "With a scenario the danger is that you envisage an outcome and then backtrack to today's starting point. Scenarios are typically written by committee, to reach a consensus. Often they are presented as a menu of choices, for example for politicians. They are less suitable when you want to explore what is most likely to happen." And, Rühl adds, the broader the scenarios become - and the presumptions on which they are based - the more meaningless they tend to be.

A point-forecast, on the other hand, "forces you to put all your cards on the table", says Rühl. "Nothing focuses the mind of the analyst as much as the necessity to make a point prediction. Large economic institutions like the IMF and World Bank do this. They don't do scenarios for a reason."

Rühl explains how the Energy Outlook is written. “We go around, try to collect the best information available, from inside and outside the company. But, quite like the Statistical Review, in the end the Outlook is written by the Economics department. Not by a corporate committee. Given its purpose, this helps to maintain standards, legitimacy and edge. The only debates I ever had in this regard is how to say things, not what or whether to say something. For example, we were among the first to observe that it was very unlikely for the world to contain global CO2 concentrations within 450 ppm, as people would like to see. Perhaps not an easy thing to say so for a big oil company. But there was never a question whether we should say it or not. It was a forecast, and so we said it is what we think will happen, not what we like to happen.”

This does not mean, Rühl adds, that the Outlook is literally claiming to predict the future. "It is to the bets of our knowledge. This includes knowing that events will occur, such as disruptive technological changes - that are unpredictable. We know they will happen, but we can't know when or in what field, and so we don't try to guess them. We also know that people have the ability to respond to similar situations in different ways. All this makes for humble claims on the crystal ball. And it's one reason we keep the forecast to 20 years. Anything longer will become too uncertain."

Nevertheless, although any Outlook is "likely to be wrong somewhere", says Rühl, its value lies in the information it provides for analysts and decision-makers to base current strategic and business decisions on.

| Scenarios are typically written by committee, to reach a consensus |

Dead and stale

The major energy “force” that is currently at work in the world, as identified by the most recent BP Energy Outlook, is the increasing impact of unconventional oil and gas on global energy markets. “We were one of the first to identify the importance of unconventionals in the US. This revolution is now going global”, says Rühl. “It will have a huge impact on how the energy world will look in 2030.”

Although most people are by now aware of the shale gas and tight oil revolution in the US, and the possibility that this will be replicated throughout the world, they still miss the essential point about it, notes Rühl. This is that it has been the result of free access and competition – of market forces at work. “What you see is how market forces over a decade, and responding to a high prices and high demand, were capable of changing the nature of supplies. Markets do this when they are left free to operate: they come up with new things. And not just shale gas or tight oil. Renewables as well.”

That is why, says Rühl, the revolution happened in the US, and not for example in China or Venezuela, which have just as much unconventional resources at their disposal. “Resource availability is actually a very poor predictor of future production growth. First and foremost you need free access. Competition. A fair investment climate. Many people lost their shirt at first in the US, trying to develop technologies to access shale resources, mostly by small companies, with big companies caming in only later. Things happened because of above-ground factors: private ownership of land, a sophisticated service sector and infrastructure that emerges only after many years of competition, including deep financial markets to hedge risks. At the same time nothing came out of countries like China, Venezuela, or Mexico, which have similar resource endowments.”

What the unconventional revolution shows, then, says Rühl, is “the ability of the energy system to generate technological change and innovation when market forces are allowed to work. The energy system is so big that outside observers often think it is stale. But it is not. It follows the rules of competition but because it is so large it follows them slowly. It is characterized by a tremendous degree of technological innovation, but this remains hidden oftentimes. It is a slow-moving beast, yes – but it does move.”

Upstream surprises

What the most recent Outlook implies, says Rühl, is that the market is responding to high demand and high prices by producing more of the same (oil, coal, gas, nuclear) as well as new supplies. “Around 2030 we see almost 20% of energy supplies delivered by shale gas and tight oil and 17% by renewable energy. The rest, some 60%, is more of the same.” Rühl adds that “compared to others, we have been conservative in our projections of unconventional growth. North America could produce more. China, Russia and others could kick in faster, so there remains a potential for surprises which then would also translate into faster geopolitical changes.”

Of course many people do not like the idea of the Age of Fossil Fuels being extended by new oil and gas. They would like to see a much faster development of renewable energy. What does Rühl have to say to them? “I try to focus on the need for renewables to copy a page from the success of the fossil fuels in constantly generating technical change and being able to reinvent themselves. They can do this by being subjected to market forces.”

The key problem with renewable energy, in Rühl's view, is that, as a subsidized sector, it is less exposed to competition. "When you have a subsidized fuel expanding faster than its cost efficiency, the amount of subsidies paid has to expand with it. At a certain point this may become too expensive and no longer tolerable to society. The subsidized energy becomes a victim of its own success. This is what is happening in Europe right now."

Rühl makes an interesting comparison between renewable energy today and the development of nuclear energy in the 1970s and 1980s, where the same thing happened. “Nuclear energy stopped growing and hit a glass ceiling in the 1980, for a host of reasons. But nuclear energy was also heavily subsidized – you cannot get private insurance for the cost of an accident, this will always be socialized. This is just one example. Costs failed to come down as envisaged. And so at some point it had lost acceptability without having lost the need for subsidization. It was no longer cost efficient while subsidies continued. That’s when it became too expensive.”

Actually, renewable energy is in a better situation today than nuclear power was back then, Rühl believes. “Renewable energies are simpler and sturdier and more easily transferable. For example, when nuclear power hit a 2% share of global power generation in 1971, it was present in 14 countries. When wind power hit this threshold exactly 40 years later, it was present in 92 countries. The production as well as application of wind power is much more widespread and it may therefore easier become subject to competition.”

Still, he adds, “that’s no guarantee for success. The really really big question is - how do you take renewables out of their subsidized shelter and expose them to competition?”

Does Rühl believe that international oil companies like BP could play a major role in the development of renewables? “They could, yes. But only if ir promised to become a real market. Look at BP. We had to more or less go out of solar, because one needs to get away from areas that are heavily subsidized if one believes this is unsustainable. Now we concentrate on areas that we see as on the verge of becoming competitive, like wind onshore in the US. We try to go where the economics have a chance to survive. In some areas, where more fundamental innovation is needed, we concentrate on R&D. In biofuels, for example, we work with the University of Berkeley where people with very big heads are trying to make possible next generation biofuels, because we know that biofuels growth from foodstuff has its limits.”

Rühl notes that “to become a driver of developments rather than limping behind what is politically correct, may be difficult – but in the world of renewables it seems also necessary.”

What goes for renewables, also goes for CO2 emissions, says Rühl: limiting carbon emissions is best be done by harnessing the market. "When you compare the growth of GDP to the growth of energy consumption, you see a pair of scissors opening up very nicely.

| To become a driver of developments rather than limping behind what is politically correct, may be difficult, but it is also necessary in the world of renewables |

Pipeline economics

The story of today’s global gas markets is also a story of long-term market forces at work, says Rühl. “The gas market is changing from two sides. There’s shale gas, and there is the increasing integration of the global gas trade, which is also a massive development. This has two components to it. One, the rapid growth of LNG, which is projected to grow at 4.3% per year, twice as fast as consumption, and today already account for 10% of supply. Second, the physical integration of gas markets through the development of infrastructure: terminals, regasification and LNG plants , and so on.”

The result of all this is that spot markets keep growing at the expense of long-term and oil-indexed contracts. Rühl notes that this is “not a smooth process”. “The addition of new supplies of LNG is lumpy. So sometimes you may even see periods when spot prices may be higher than long-term prices.”

But he believes the process of untying the oil-gas price knot and the decline of long-term contracts is irreversible. “You have to go back to the basics to see what is happening. Gas is the only fuel whose price is tied to another fuel. There are good reasons for this historically. Gas was a pipeline fuel. So up to a point you had one supplier, one buyer – a bilateral monopoly but no market. That’s why the price was tied to something else. Now fast forward to the first LNG projects. Their economics were identical to pipeline economics: You had 25-30 year contracts, with volume targets and prices tied to oil. This system was gradually undermined, first before the crisis by Asian buyers who bid away LNG cargoes from the Atlantic Basin, then after the crisis by suppliers who could not sell their LNG to the US anymore and started selling on Asian spot markets. Next, a wave of new supplies from the Middle East came in, while at the same time the European power markets were liberalized. This is a long-term process in the direction of integrated markets and spot trading which won’t be stopped anymore.”

Rühl adds that “this reminds me very much of the history of the oil tanker. The first oil tanker – which was invented by Shell, I am sorry to say – went up and down between Rotterdam and Sumatra. It took many decades – and huge investments in infrastructure – before a real market started to develop.”

The BP man points out that the market process is further advanced in Europe than in Asia thanks in part to the liberalization of the European power market. “At the time when a lot of new LNG hit the market and demand was low because of the crisis, there was a new situation in Europe. Smaller utilities were able to source their own supplies on the spot market, thanks to the liberalization, and to undercut the large utilities. That’s why the Eons and Gaz de Frances of this world had to go to Gazprom to ask for price cuts, which they eventually got. In Asia, utilities are still monopolies, more likely to pass on prices to customers, since they don’t need to be not bothered by competition.”

|

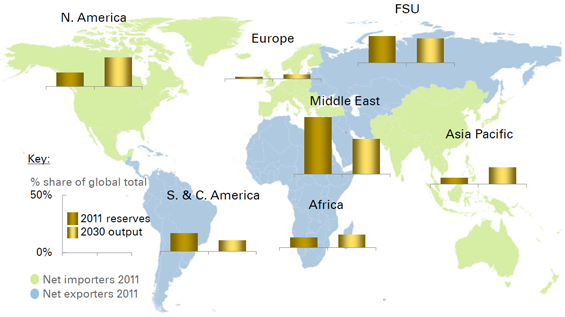

| BP Energy Outlook 2030 - Distribution of oil and gas reserves: importing regions more likely to turn reserves into production - (c) BP |

Down the tubes

So what lies ahead for our world energy system? What Rühl sees coming, based on the research of his group, is an ever wide range of energy sources being used (i.e. a reduced reliance on any single energy resource), an accelerating convergence of regional markets and continued improvement in energy efficiency – all driven by market forces.

He also expects that the unconventional energy revolution will lead to less 'resource nationalism'. "More and more people will discover they are sitting on energy resources and will demand from their governments that these be developed. This will put pressure on governments to attract private investment. Barriers to entry might well go down."

He notes that international (private) oil companies (IOCs) have been explosed to more competition from national (state-owned) oil companies (NOCs),

| More and more people will discover they are sitting on energy resources and will demand from their governments that these be developed |

For IOCs the state-backed competitive NOCs, including the Chinese ones, are "a challenge", Rühl acknowledges, but also an opportunity as markets open up. He notes that "any market that becomes deeper and broader offers opportunities to specialize. It will become rare, I think, for companies not to specialize in some things either implicitly or explicitly."

What Rühl does not see is any constraints on resource availability. "Peak oil is down the tubes. For the umpteenth time. In fact, we have never run out of anything. The human capacity to innovate, if left free to develop, prevents this."

This may sound optimistic, but Rühl is no utopian. "I realize the arrogance that comes with such a statement. I am not saying everything will turn out fine, no matter what we do. Population growth is putting huge pressure on the planet. Species are dying out at an alarming rate. So I think there is a greater danger of us destroying the planet inventing new things than of us going back to the Stone Age."

|

Christof Rühl is Group Chief Economist and Vice President of BP plc. He manages BP's global Economics Team, providing economic input into the firm's commercial decisions. BP's Economics Team produces the annual Statistical Review of World Energy and the Global Energy Outlook. Prior to joining BP, Rühl worked at the World Bank (1998-2005) where he served as the Bank's Chief Economist in Russia and in Brazil. Before that, he worked in the Office of the Chief Economist at the EBRD (Economic Bank for Reconstruction and Development) in London. He started his career as an academic economist, first in Germany and from 1991 as Professor of Economics at the University of California in Los Angeles. |

Discussion (0 comments)