Beyond the Hype: What U.S. LNG Exports Could Mean for EU Gas Markets

January 27, 2016

on

on

In a historic milestone, the U.S. will begin exporting liquefied natural gas (LNG) out of the lower 48 states to world markets in early 2016 on the heels of an unprecedented gas glut and low prices stemming from domestic shale gas boom. With five liquefaction trains underway at Sabine Pass export terminal in Louisiana, exports from this terminal will be one of the first of four export terminals in the U.S. that are expected to become operational in 2016. [1] There are, at least, 10 other U.S. LNG export projects awaiting approval. The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that the total U.S. LNG export capacity would reach close to 90 billion cubic meters (bcm) a year by 2020. [2] According to Cheniere Energy, Inc., an American energy company that started LNG production for exports at the Sabine Pass terminal on December 30, 2015, nearly 50% of the U.S. LNG exports is expected to go to Europe. [3]

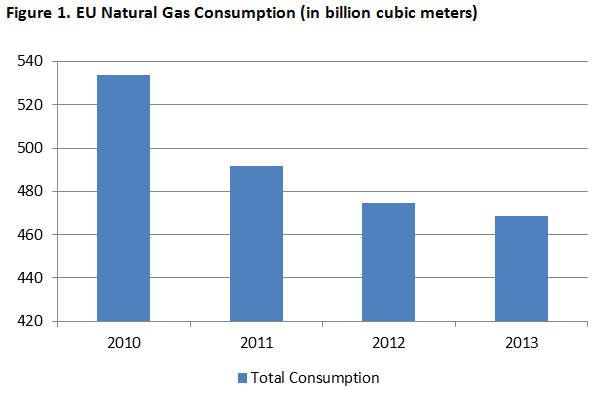

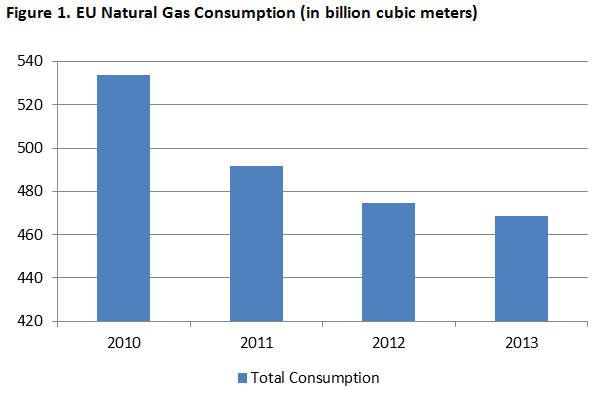

Although natural gas consumption in the EU has been steadily declining since 2010 (See Figure 1), IEA forecasts that European gas demand will rise by nearly one-third by 2020. In light of Europe’s search for natural gas supply security, particularly given uneasy relations with its most important gas supplier, Russia, speculations have been rife on the role of the U.S. LNG supplies to the EU. Some gas analysts believe the U.S. LNG exports will dramatically improve European energy supply security to the point of replacing Russian gas; others argue that the impact will be small. This article will assess the impact U.S. LNG exports may have on the EU and factors that will determine its effect on European energy security.

Source: EIA

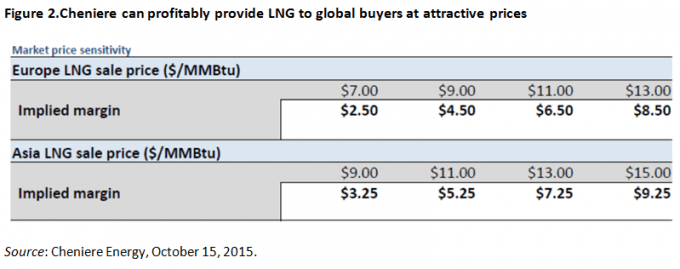

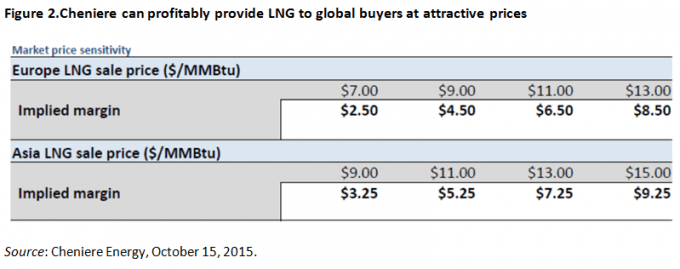

Risking massive investments at the time when LNG prices are down in some of the profitable markets in Asia and Europe and facing competition from bigger LNG exporters, such as Australia and Qatar, proponents of U.S. natural gas exports are betting on the recovery of gas prices. Cheniere hopes for profits in the European gas market since the Asian market is dominated by Australian LNG supplies. Because Cheniere’s contracts with buyers will have no destination clauses, [4] the company hopes that it will provide an agreeable option to customers. In fact, most of U.S. gas supplies are expected to be free of destination clauses. It will give European buyers a chance to take advantage of any arbitrage by buying LNG from U.S. suppliers at spot prices and reselling them at higher prices. According to Cheniere’s estimates, the company could double or triple its profits in Europe and Asia compared to the domestic market (See Figure 2), even under the global low-price environment.

Another advantage of U.S. LNG supplies to international customers is their prices are not indexed to the price of oil, unlike most other LNG and pipeline contracts, including those between the EU and Russia. The U.S. uses current Henry Hub pricing with an adder of a toll. Such gas pricing structure and the lack of destination clauses in U.S. LNG contracts is likely to boost more flexibility and create a potential arbitrage opportunity for LNG buyers.

The first recipient of the U.S. LNG in Europe is expected to be Lithuania, which signed a non-binding agreement with the U.S. in early 2015. With new regasification terminals coming online in other European countries to import LNG, U.S. energy companies are eyeing greater market share both in Western and Eastern Europe. In light of the EU’s policy of diversification of energy suppliers and the goal to reduce Russian energy dominance, the U.S. LNG can play a role in the shift. However, this role is unlikely to be a game changer for the EU since global LNG supply and demand dynamics will determine the EU’s access to LNG, while a price difference between the Russian pipeline gas and global LNG will affect the EU’s economic rationale on where to buy gas. In addition, EU members still have long-term gas contracts with Russia that they cannot abandon.

According to the IEA, European LNG imports are expected to double by 2020. [5] IEA predicts that European gas demand will be within a 150-160 bcm/year range in coming years due to the fall in domestic gas output and a shift from coal-fired power generation to gas. Particularly, the loss of swing production in the Netherlands will necessitate more gas imports. Meanwhile, domestic drilling of unconventional gas from shale formations is yet to overcome the EU’s concerns over its environmental impact. The expected rise in gas demand and the decline in indigenous production rates will keep many of the EU countries dependent on Russian gas. The U.S. LNG alone is insufficient to replace Russian gas in the EU.

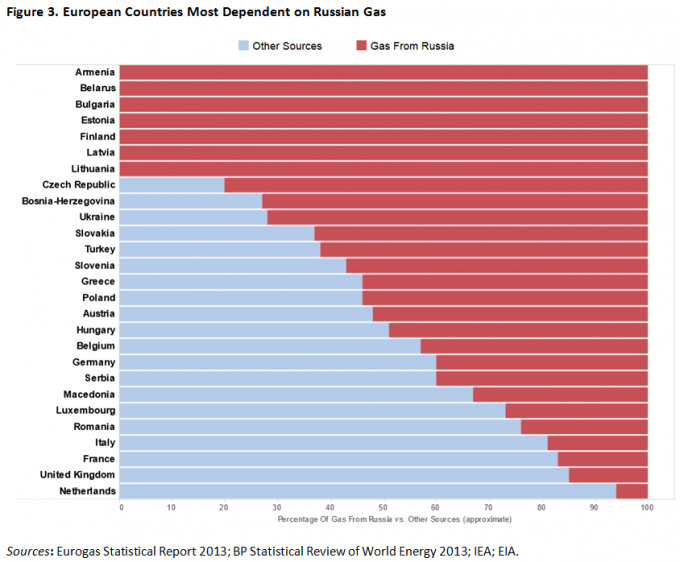

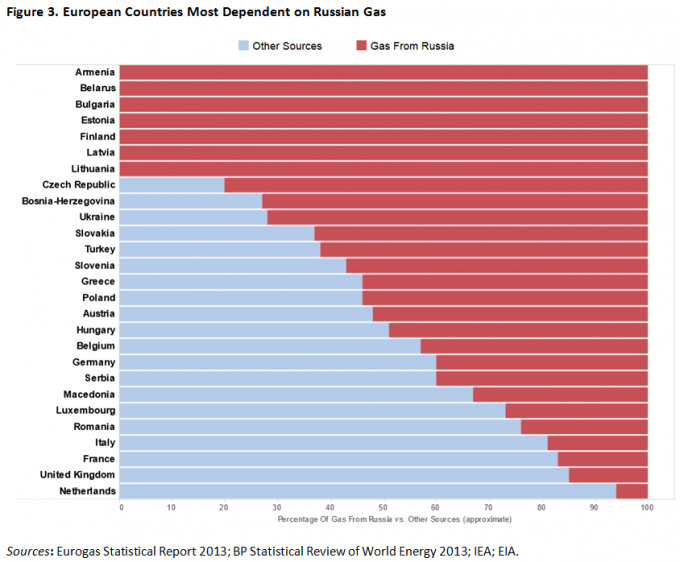

Furthermore, since the Baltic, Central, and South-Eastern European gas markets are either completely or more than 50% dependent on Russian gas (See Figure 3), moving away from it will be more difficult for them. These regions have historically relied on a unidirectional pipeline infrastructure that was developed to move Soviet gas from east to west and they continue to lack necessary north-south interconnecting pipelines. Although there is some progress in enhancing pipeline linkages among Central and South-Eastern European countries and in reversing gas flows within the EU to reduce dependence on Russian gas, most countries in these regions are landlocked, which complicates their access to LNG. In addition, liberalization of prices and opening of gas markets to competition, as mandated by the EU’s 2009 Third Energy Package, continue to face obstacles in Central and Eastern European countries. As a result, parts of the EU continue to suffer from internal bottlenecks and access to more diverse gas supplies and equitable prices.

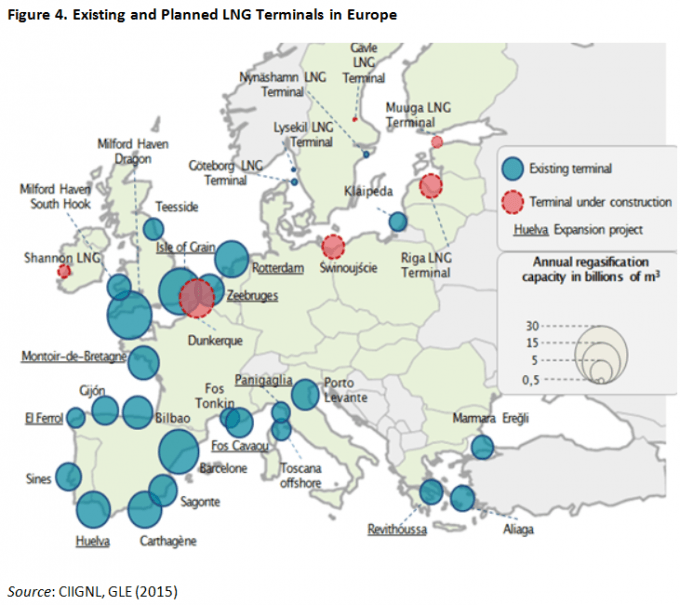

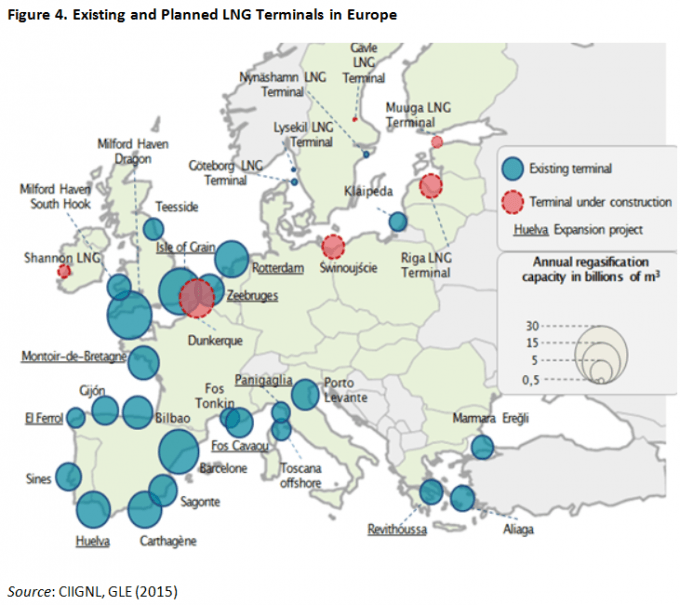

In contrast to Central and South-Eastern Europe, Western European countries are less exposed to Russian gas price and volume movements by sourcing additional gas supplies from Norway, North Africa, and LNG. Indeed, Western Europe has over 80% of the EU’s LNG regasification and import terminals (See Figure 4), while there is currently not enough LNG importing infrastructure in place in Central and South-Eastern Europe to replace Russian gas. Poland’s Swinoujscie LNG import terminal due to open in 2016, with a planned initial capacity of 5 bcm, and Lithuania’s new floating Klaipeda LNG regasification terminal, with a capacity of 4 bcm and operational since 2014, are modest steps towards diversification. It is still unclear whether the new LNG regasification infrastructure in Lithuania and Poland would be cheaper compared to the Russian gas. The main factors for investing in future LNG infrastructure in the EU will be driven by the price of LNG vis-à-vis Russian pipeline gas and global LNG demand and supply. For example, future LNG demand and prices in Asia, the region that paid a premium rate for LNG until supply outstripped demand in recent months and prices fell, will inevitably affect the availability of LNG from the U.S. and other suppliers to Europe.

Since the fall of gas demand in the EU following the 2008 economic recession and more gas entering the spot market, most European countries managed to renegotiate their long-term gas contracts and rates with Gazprom. [6] Faced with an anticipated LNG glut in Europe in coming months [7] and an increasing competition from other gas suppliers, including the U.S., the Russian gas monopolist is likely to further reduce its gas prices. A potential change that may arise from this could be greater gas-on-gas competition in the EU due to more diverse gas supplies – both LNG and pipeline – and an increased spot gas at trading hubs in the EU, which may further widen the spot indexation vis-à-vis gas prices tied to oil. In light of these developments, the challenge for the EU will be to create a single effective gas market and competitive prices across the Union by improving the poor connectivity with and among a patchwork of its national markets, particularly, those in Central and South-Eastern Europe.

Image: Golden Pass LNG, Sabine Pass. By: Roy Luck. CC-BY licence.

Although natural gas consumption in the EU has been steadily declining since 2010 (See Figure 1), IEA forecasts that European gas demand will rise by nearly one-third by 2020. In light of Europe’s search for natural gas supply security, particularly given uneasy relations with its most important gas supplier, Russia, speculations have been rife on the role of the U.S. LNG supplies to the EU. Some gas analysts believe the U.S. LNG exports will dramatically improve European energy supply security to the point of replacing Russian gas; others argue that the impact will be small. This article will assess the impact U.S. LNG exports may have on the EU and factors that will determine its effect on European energy security.

Source: EIA

What to Expect from U.S. LNG Exports?

Risking massive investments at the time when LNG prices are down in some of the profitable markets in Asia and Europe and facing competition from bigger LNG exporters, such as Australia and Qatar, proponents of U.S. natural gas exports are betting on the recovery of gas prices. Cheniere hopes for profits in the European gas market since the Asian market is dominated by Australian LNG supplies. Because Cheniere’s contracts with buyers will have no destination clauses, [4] the company hopes that it will provide an agreeable option to customers. In fact, most of U.S. gas supplies are expected to be free of destination clauses. It will give European buyers a chance to take advantage of any arbitrage by buying LNG from U.S. suppliers at spot prices and reselling them at higher prices. According to Cheniere’s estimates, the company could double or triple its profits in Europe and Asia compared to the domestic market (See Figure 2), even under the global low-price environment.

Another advantage of U.S. LNG supplies to international customers is their prices are not indexed to the price of oil, unlike most other LNG and pipeline contracts, including those between the EU and Russia. The U.S. uses current Henry Hub pricing with an adder of a toll. Such gas pricing structure and the lack of destination clauses in U.S. LNG contracts is likely to boost more flexibility and create a potential arbitrage opportunity for LNG buyers.

The first recipient of the U.S. LNG in Europe is expected to be Lithuania, which signed a non-binding agreement with the U.S. in early 2015. With new regasification terminals coming online in other European countries to import LNG, U.S. energy companies are eyeing greater market share both in Western and Eastern Europe. In light of the EU’s policy of diversification of energy suppliers and the goal to reduce Russian energy dominance, the U.S. LNG can play a role in the shift. However, this role is unlikely to be a game changer for the EU since global LNG supply and demand dynamics will determine the EU’s access to LNG, while a price difference between the Russian pipeline gas and global LNG will affect the EU’s economic rationale on where to buy gas. In addition, EU members still have long-term gas contracts with Russia that they cannot abandon.

LNG: Not an EU-wide panacea

According to the IEA, European LNG imports are expected to double by 2020. [5] IEA predicts that European gas demand will be within a 150-160 bcm/year range in coming years due to the fall in domestic gas output and a shift from coal-fired power generation to gas. Particularly, the loss of swing production in the Netherlands will necessitate more gas imports. Meanwhile, domestic drilling of unconventional gas from shale formations is yet to overcome the EU’s concerns over its environmental impact. The expected rise in gas demand and the decline in indigenous production rates will keep many of the EU countries dependent on Russian gas. The U.S. LNG alone is insufficient to replace Russian gas in the EU.

Furthermore, since the Baltic, Central, and South-Eastern European gas markets are either completely or more than 50% dependent on Russian gas (See Figure 3), moving away from it will be more difficult for them. These regions have historically relied on a unidirectional pipeline infrastructure that was developed to move Soviet gas from east to west and they continue to lack necessary north-south interconnecting pipelines. Although there is some progress in enhancing pipeline linkages among Central and South-Eastern European countries and in reversing gas flows within the EU to reduce dependence on Russian gas, most countries in these regions are landlocked, which complicates their access to LNG. In addition, liberalization of prices and opening of gas markets to competition, as mandated by the EU’s 2009 Third Energy Package, continue to face obstacles in Central and Eastern European countries. As a result, parts of the EU continue to suffer from internal bottlenecks and access to more diverse gas supplies and equitable prices.

In contrast to Central and South-Eastern Europe, Western European countries are less exposed to Russian gas price and volume movements by sourcing additional gas supplies from Norway, North Africa, and LNG. Indeed, Western Europe has over 80% of the EU’s LNG regasification and import terminals (See Figure 4), while there is currently not enough LNG importing infrastructure in place in Central and South-Eastern Europe to replace Russian gas. Poland’s Swinoujscie LNG import terminal due to open in 2016, with a planned initial capacity of 5 bcm, and Lithuania’s new floating Klaipeda LNG regasification terminal, with a capacity of 4 bcm and operational since 2014, are modest steps towards diversification. It is still unclear whether the new LNG regasification infrastructure in Lithuania and Poland would be cheaper compared to the Russian gas. The main factors for investing in future LNG infrastructure in the EU will be driven by the price of LNG vis-à-vis Russian pipeline gas and global LNG demand and supply. For example, future LNG demand and prices in Asia, the region that paid a premium rate for LNG until supply outstripped demand in recent months and prices fell, will inevitably affect the availability of LNG from the U.S. and other suppliers to Europe.

Since the fall of gas demand in the EU following the 2008 economic recession and more gas entering the spot market, most European countries managed to renegotiate their long-term gas contracts and rates with Gazprom. [6] Faced with an anticipated LNG glut in Europe in coming months [7] and an increasing competition from other gas suppliers, including the U.S., the Russian gas monopolist is likely to further reduce its gas prices. A potential change that may arise from this could be greater gas-on-gas competition in the EU due to more diverse gas supplies – both LNG and pipeline – and an increased spot gas at trading hubs in the EU, which may further widen the spot indexation vis-à-vis gas prices tied to oil. In light of these developments, the challenge for the EU will be to create a single effective gas market and competitive prices across the Union by improving the poor connectivity with and among a patchwork of its national markets, particularly, those in Central and South-Eastern Europe.

Image: Golden Pass LNG, Sabine Pass. By: Roy Luck. CC-BY licence.

Read full article

Hide full article

Discussion (0 comments)