Book review: Acoustics in Performance

The book succeeds in quantifying and qualifying many sensations associated with hearing in large rooms and even larger buildings, specifically concert halls and places of worship as the author Honeycutt calls them. Every chapter in the book first describes the ways in which the communication problem posed by poor acoustics is worded by the ‘parties’ involved: like the vocalist bothered by audience babble, the audience bothered by echoes and HVAC hum, and the hapless sound technician finding that his carefully wrought mixing console settings are useless once the hall is full of people wearing coats. Honeycutt’s book addresses all these aspects and more.

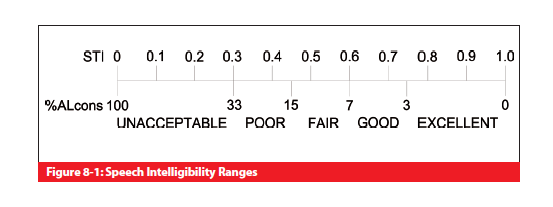

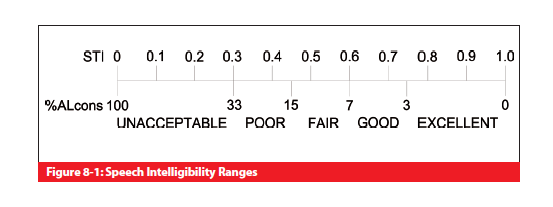

Another remarkable thing about the book is the solid basis of theory it presents to address and dissect problems that at first blush appear to be an Gordian knot of physics, acoustics and electronics on the one hand, and human (= highly subjective) perception on the other. Like the sound technician starting out fairly quietly but constantly turning up each and every instrument and microphone level until a wall of sound is obtained simply to mask poorly performing artists. This is the “volume-overpowers-everything” myth which is carefully debunked in the book, first by explaining an anchoring all physics units involved, like the well-known watts and decibels but also %ALcons, a rarely seen but very useful unit to express articulation loss of consonants. Admittedly I had never heard of it (pun intended).

Another remarkable thing about the book is the solid basis of theory it presents to address and dissect problems that at first blush appear to be an Gordian knot of physics, acoustics and electronics on the one hand, and human (= highly subjective) perception on the other. Like the sound technician starting out fairly quietly but constantly turning up each and every instrument and microphone level until a wall of sound is obtained simply to mask poorly performing artists. This is the “volume-overpowers-everything” myth which is carefully debunked in the book, first by explaining an anchoring all physics units involved, like the well-known watts and decibels but also %ALcons, a rarely seen but very useful unit to express articulation loss of consonants. Admittedly I had never heard of it (pun intended).

In the future, instead of the boring “testing-one two-three”, try “pa-ta-da” in the microphone and then ask a number of listeners what they actually heard. The outcome is sure to pinpoint a defect in the sound system being set up for the performance. For example, the test speaker’s ‘p’ sound may be damped by velour curtains above the stage and loose some of its plosive characteristic sound to the extent of being heard as a ‘b’ by the audience. The same with the noise component so essential in the ‘t’ voiceless consonant — it may be filtered out by a piece of absorptive ceiling and approach the voiced consonant ‘d’.

Another remarkable thing about the book is the solid basis of theory it presents to address and dissect problems that at first blush appear to be an Gordian knot of physics, acoustics and electronics on the one hand, and human (= highly subjective) perception on the other. Like the sound technician starting out fairly quietly but constantly turning up each and every instrument and microphone level until a wall of sound is obtained simply to mask poorly performing artists. This is the “volume-overpowers-everything” myth which is carefully debunked in the book, first by explaining an anchoring all physics units involved, like the well-known watts and decibels but also %ALcons, a rarely seen but very useful unit to express articulation loss of consonants. Admittedly I had never heard of it (pun intended).

Another remarkable thing about the book is the solid basis of theory it presents to address and dissect problems that at first blush appear to be an Gordian knot of physics, acoustics and electronics on the one hand, and human (= highly subjective) perception on the other. Like the sound technician starting out fairly quietly but constantly turning up each and every instrument and microphone level until a wall of sound is obtained simply to mask poorly performing artists. This is the “volume-overpowers-everything” myth which is carefully debunked in the book, first by explaining an anchoring all physics units involved, like the well-known watts and decibels but also %ALcons, a rarely seen but very useful unit to express articulation loss of consonants. Admittedly I had never heard of it (pun intended).In the future, instead of the boring “testing-one two-three”, try “pa-ta-da” in the microphone and then ask a number of listeners what they actually heard. The outcome is sure to pinpoint a defect in the sound system being set up for the performance. For example, the test speaker’s ‘p’ sound may be damped by velour curtains above the stage and loose some of its plosive characteristic sound to the extent of being heard as a ‘b’ by the audience. The same with the noise component so essential in the ‘t’ voiceless consonant — it may be filtered out by a piece of absorptive ceiling and approach the voiced consonant ‘d’.

Read full article

Hide full article

About Jan Buiting

Jan Buiting (1958) has been active in electronics and ways of expressing it since the age of 15. Attempts at educating Jan formally have so far yielded an F-class radio amateur license, an MA degree in English, a Tek Guru award, and various certificates in ele... >>

Discussion (0 comments)