"European energy companies risk missing out on a tremendous opportunity"

on

The geo-economic blessings of shale gas

"European energy companies risk missing out on a tremendous opportunity"

While countries like China, India and Australia are jumping on the shale gas bandwagon, European policymakers and energy companies seem reluctant to embrace this new energy resource that was first developed in the United States. Frank Umbach, Associate Director of the new European Centre for Energy and Resource Security (EUCERS), urges the European energy industry to overcome its skepticism and the EU and its Member States to start supporting unconventional gas production. 'Shale gas offers a tremendous opportunity to change Europe's increasingly vulnerable geopolitical and geo-economic position in the world. It is time that we in Europe start seizing this opportunity instead of only focusing on its potential drawbacks.'

|

| Workers extract shale gas at Chesapeake's gas site in Texas, USA (photo: Matt Nager/Bloomberg) |

Umbach, a veteran in geopolitical affairs, knows what he is talking about. He lived and worked in Brussels, Berlin, Moscow, Tokyo and Washington and has written profusely on EU and German energy relations with Russia, the Ukraine and Asia. After spending 11 years at the German Council on Foreign Relations, he last year joined the European Centre for Energy and Resource Security (EUCERS) in London. EUCERS is a relatively new think tank. It was founded in September last year by the Department of War Studies at King’s College, specifically to study energy security issues from a geopolitical perspective. Not coincidentally, EUCERS’s Executive Director is also a German – Dr. Friedbert Pflüger, a former German Deputy Minister of Defence. The new institute believes that energy security cannot be achieved by EU member states independently and emphatically wants to contribute to a ‘common European research policy’. (Not to mention the fact that of course German energy companies are heavily involved in the UK energy market.)

No evidence

Umbach has recently co-authored (with Maximilian Kuhn) a report for EUCERS on ‘Strategic Perspectives of Unconventional Gas’, tellingly subtitled ‘A game changer with implications for the EU’s energy security’. The report, which stresses the geopolitical importance of unconventional gas and got a lot of attention in the British media, came out of a workshop that EUCERS held earlier this year for the

| 'There is a strong feeling among some companies not to upset Russia in any way' |

Britain, then, seems ready to follow in the footsteps of Poland, which has recently announced major investments in shale gas exploration and production in an ambitious attempt to reduce dependence on Russian energy supplies. Representatives of the Polish government have also recently visited Brussels to convince EU policymakers that shale gas should be given broad EU support.

But for the moment Poland and the UK are outliers. The European Commission has not committed itself yet on shale gas. In its “Energy 2020 Strategy” which came out in November 2010, it merely says that ‘the potential for further development of EU indigenous fossil fuel resources, including unconventional gas, exists and the role they will play must be assessed in all objectivity’. Similarly, the EU heads of state at their energy summit on 4 February said that ‘in order to further enhance its security of supply, Europe’s potential for sustainable extraction and use of conventional and unconventional (shale gas and oil shale) fossil fuel resources should be assessed’.

The German government has not taken a stand yet either, but foreign energy companies that are exploring for shale gas in Germany are facing increasing local opposition. In the meantime, the French government has issued a temporary moratorium on unconventional gas activities until it has investigated the matter further. It is expected that it will publish two reports in June – on the environmental and economic effects of shale gas – that will be instrumental in deciding on French policy.

Psychological barrier

The cautiousness on the part of European policymakers may not come as a great surprise, but the reluctance of European energy companies to go for shale gas, is more difficult to understand. In a recent interview with European Energy Review, Jean-François Cirelli, President of Eurogas and President of French energy company GDF-Suez, said that he does not expect shale gas to become as

| 'They are becoming more interested. There is a lot going on behind the scenes' |

Umbach notes that in addition to their strong commitment to the existing gas market structure, including their strong ties with Gazprom, the energy companies face another obstacle. ‘They lack technical and management expertise’, he says. ‘This creates a psychological barrier, too.’

However, Umbach has noted a change in the companies’ attitude lately. ‘They are becoming more interested. There is a lot going on behind the scenes. A consensus is growing that shale gas could become important after 2020. That’s already a big change from the way they used to look at it.’ He thinks that the price conflicts Eon Ruhrgas and others have had with Gazprom may have something to do with this. ‘This has stimulated them to come up with a new strategy, to pay more attention to diversification.’

According to Umbach, who speaks Russian and had warned of a Russian-Ukrainian gas conflict before it broke out, the Russians are now ‘very nervous’ about the shale gas developments. The reason for this is that the planned exploitation of their huge conventional gas reserves in Yamal and Shtokman is ‘extremely expensive’ and could become endangered if shale gas production were to take off in Europe. The South Stream pipeline also looks less attractive in that light. ‘They are now trying to corner the market with long-term contracts’, says Umbach. ‘This is a tremendous problem for them.’

Much weaker

|

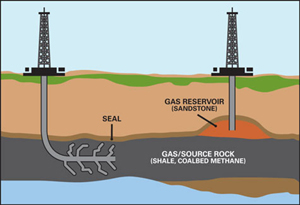

| Unconventional (left) vs. conventional (right) gas production (illustration: DTE energy) |

Umbach and Kuhn note in the EUCERS report that the EU already imports 50% of its gas, and this will rise to 70% in the next 20 to 30 years. For oil and coal, dependency is even higher. At the same time, virtually all experts, such as the International Energy Agency, expect energy prices to rise considerably in the coming decades as traditional energy resources will become scarcer. Major geopolitical conflicts over energy cannot be ruled out. Thus, the production of unconventional gas, even if it only manages to offset the natural decline of the EU’s current domestic production, could have a disproportionately large impact on Europe’s position in the global energy market. ‘Even if we get only a small portion of the resources out of the ground, this will have a much greater impact on market structure than is commonly understood’, says Umbach.

In fact, as the EUCERS report notes, even if the EU does not engage in production of shale gas, developments elsewhere in the world will serve to weaken Russia’s position in the market. A recent study from the US Energy Information Administration notes that China holds 50% more unconventional gas reserves than the US and international companies like Shell and BP are already active in China to

| 'We won't really know what the potential is until the results of the first test explorations come in' |

Pudding

So what is Europe’s real unconventional gas potential? EUCERS cites figures from the International Energy Agency (IEA) which estimate total recoverable reserves at between 33 and 38 tcm (trillion cubic metres). This is 15 times as much as current conventional reserves and good for 60 years of demand. However, as technical consultancy Wood Mackenzie has pointed out, European unconventional plays are more complex, deeper and less porous than those in North America, so the real economically recoverable resource base remains uncertain. ‘Europe currently lacks any detailed and reliable geological study of its own’, says Umbach. ‘We won’t really know what the potential is until the results of the first test explorations come in.’ He adds hopefully that ‘we do know that the reserves of new energy resources tend to increase rather than decrease over time as technological development takes place.’

An even bigger and more crucial uncertainty is the potential costs of shale gas production in Europe. The EUCERS report concedes that according to estimates from the Oxford Institute of Energy Studies, production costs in Europe could be four times as high as in the US. This is because drilling costs and labour costs are much higher here than in North America. Europe has very few rigs compared to the US. Ironically, this could means, as EUCERS notes, that shale gas could only become profitable if its price could be tied to the long-term oil-linked contracts that Russia and other major producers maintain with Europe. Spot market prices could be too low and volatile to support European shale gas production. But the fact is, says Umbach, that much is still very uncertain. For instance, geological data about porosity and permeability of shale and coal seams in Europe is almost unknown, so it’s difficult to predict how much production would cost. ‘Again, the proof of the pudding will be in the eating.’

|

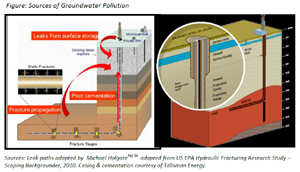

| Figure: Sources of Groundwater Pollution (click to enlarge) (source: Talisman Energy) |

The good news on this, says Umbach, is that both these ‘leak paths’ can be prevented by ‘good oil field practices and state of the art cementation techniques’. In Europe, he says, we have so much engineering experience and such strict environmental regulations, that these problems can be avoided.

Cynicism

Another potential environmental problem is the large volumes of water that are needed to unlock shale gas from the rock formations in which it occurs. This might lead to competition over water resources with the agricultural industry. However, says the EUCERS report, what is often overlooked is that up to 70% of the water used in the fracturing process can be recycled.

Nonetheless, it is clear, as Umbach concedes, that with these environmental issues, it is not going to be easy to convince the public in Europe that production of unconventional gas is desirable. ‘Public acceptance is going to be the main issue for future unconventional gas development’, notes the report –

| 'In Germany there is a general mood of cynicism among energy producers, because just about all their activities are being resisted by the public' |

But this makes it all the more urgent, says Umbach, that policymakers provide a ‘strategic perspective’ to the question of unconventional gas production. ‘The European Union should provide a clear focus. It should establish a policy framework, with investment mechanisms to stimulate shale gas exploitation. At this moment we have none of this.’ He adds, ‘in Europe we always seem to be focusing on the potential problems of a new technology. In the US and Asia they look at the positive prospects. It is time we open our minds and seize the strategic potential that unconventional gas is offering.’

|

A challenge to unconventional gas

|

Not everyone shares EUCERS’ enthusiasm for shale gas. In the US in particular a debate is raging on the supposed blessings of this new energy resource. Recently, the Post-Carbon Institute published a sharp critique of the optimistic outlook for unconventional gas conveyed by the US government and energy industry. In this report (

Not everyone shares EUCERS’ enthusiasm for shale gas. In the US in particular a debate is raging on the supposed blessings of this new energy resource. Recently, the Post-Carbon Institute published a sharp critique of the optimistic outlook for unconventional gas conveyed by the US government and energy industry. In this report (

Discussion (0 comments)