"People hate buying gasoline more than anything else"

on

Evan Thornley of Better Place on why "the oil reduction business" is the place to be

"People hate buying gasoline more than anything else"

"Batteries are getting cheaper, gasoline is getting more expensive and every single public policy variable is in favour of electric cars." This is how Evan Thornley, ex-CEO of electric car infrastructure provider Better Place sums up the future of electric vehicles. When it was created five years ago by charismatic Israeli entrepreneur Shai Agassi, Better Place rapidly became one of the most talked about green ventures. It turned conventional thinking on its head with a focus on electric cars for long-distance driving, not just for city centres, and the innovative concept of battery switch stations. Lately, with the departure of Agassi last October, and the announcement that the company is scaling back operations in North America and Australia, Better Place seems to have run into trouble. But the company has lost none of its drive, said Thornley in an interview with European Energy Review in December: "We're a little slower than we would have liked. But we're just about at that point now where it's all out there." And he is convinced electric cars have the future, because "people hate buying gasoline more than anything else."

|

| Evan Thornley (c) Israel Hayom |

The restructuring of its portfolio also saw Better Place bid adieu to Thornley in January. The lively Australian was formerly CEO of Better Place Australia, one of the markets where the company is scaling down operations. With half a life spent in Silicon Valley and the other half in public policy in Australia, Thornley described Better Place as "one of the few powerful environmental opportunities I've seen that makes immediate business sense". As the company now attempts to scale up in Israel and Denmark to prove it has a market, Thornley still sees a bright future ahead. European Energy Review met with him on a trip he took to Brussels to discuss the future of an electric car charging infrastructure in Europe, when he was still working for Better Place.

Q: Just over a year ago Better Place was predicting it would be the best-selling car in Israel and Denmark in 36 months. How does the future look today?

A: As is always the case with new technology we're a little slower than we would have liked. But we're just about at that point now where it's all out there: we have 17 out of 18 battery switch stations live in Denmark and 30 out of 38 ready in Israel, plus thousands of plug-in points in each. Our contention has always been that a full service network is a pre-condition to larger scale adoption [of electric vehicles]. We're now going to test that proposition over the coming year as we move into a fully commercial mode. The company has gone from a vision and an idea to the development of real technology and the proof of that technology - I've been driving around Israel for the last seven weeks in my electric car.

Q: Are people using your charging infrastructure? Are they driving electric cars?

A: We have the first few hundred cars running well. The most important thing for me is that people are driving long distances in electric cars - at least they are in Israel, Denmark, and now the taxi fleet at

| The most important thing for me is that people are driving long distances in electric cars - at least they are in Israel, Denmark, and now the taxi fleet at Amsterdam's Schiphol airport |

But of course that's opposite to the way electric cars have traditionally been conceived. Because we see them as range-limited we've tended to focus on short-distance drivers for whom the economics are more difficult. But the holy grail of electric cars is long-distance driving. Corporate fleets, rental cars, taxis - that's where the economics will be most attractive. And from a public policy point of view, that's where the big [CO2] emission reduction opportunity is. It's not getting the nice, climate-sensitive inner city folks who do 10,000 kilometres a year in a tiny city car to go electric, it's when you get fleet vehicles, taxis, and delivery vehicles that do a lot of driving and are often larger-scale vehicles that you can really affect emissions.

That was the central contrarian idea behind Better Place in the first place - to go for the opposite sector to what everyone else was focused on - and we're proving that's viable.

Q: To what extent does EU policy support your goals?

A: From our point of view as a global company most of the policy we're seeing in Europe is more enlightened than elsewhere in the world. Certainly the proposal for a 95g/km CO2 emission fleet average [by 2020] - which of course is easiest to meet by getting a bunch of zero emissions cars - is important. We're also seeing thoughtful policy around mandatory requirements for member states for a minimum level of public charging infrastructure and for ensuring that electricity market regulations are sympathetic to the needs of charging electric cars.

Q: In what way do electricity market regulations need to change?

A: As I said the most potent place for emission reductions is in corporate fleets - they tend to driver longer and larger cars. Those are the people you really want to move off gasoline. Now the way they're used to paying for their transport energy is very simple - all is reported separately, measured separately, can be expensed, taxes paid, accounting done. For your employees to drive an electric car and have the same convenience, you need their home electricity use to be separately measured and paid for. If you don't do that you've got a massive barrier to adoption. Is the employee supposed to bring in his home electricity bill with a highlighter pen and say please give me US$2.97 this month? It's a big issue. Ensuring separate metering is easily and cheaply done is a very important factor for mass adoption.

It also enables us to manage the electricity purchase and preferably buy from zero emission sources - that's part of our promise, to ensure we source the electricity from green sources. Our focus is on zero emissions

| From our point of view as a global company most of the policy we're seeing in Europe is more enlightened than elsewhere in the world |

The question is how easy and expensive is it [to have separate metering]. There are two options: 1) physically install a separate circuit, meter board etc - this is expensive and time consuming - or 2) allow metering for the car to occur in the household's existing circuit and just do a virtual separation. Clearly the second is much simpler, cheaper and better. This is the type of mechanism now being put forward [in Europe's alternative fuels infrastructure directive proposal] and we're very encouraged by that. While it's quite a nuanced regulatory point it will have a big impact on adoption and it will certainly have a big impact on the investment decisions of companies like ours.

Q: What other European policy initiatives are important to you?

A: Certainly car CO2 standards are important. I think there are opportunities to make them stronger. Super-credits [which means one electric car would count as 1.3 cars in calculating a carmaker's compliance with the fleet emission standard of 95g/km CO2 in 2020] are clearly valuable. In relation to that, we understand the purpose of the cap of 20,000 vehicles per manufacturer [which would be eligible for super credits] - if there is no cap, you would dilute the 95g/km average. But we propose an alternative: a bonus malus system where those who over-deliver have a better deal and those who fail to deliver a disadvantage [i.e. a carmaker whose fleet has a lower than market-average share of ultra-low carbon vehicles must comply with a more stringent CO2 target, while one with a higher than market-average share can comply with a more lenient target]. That way you would maintain the target but you wouldn't limit the benefits car manufacturers can get by putting clean cars on the road.

Q: What about the minimum requirements for electric charging infrastructure that the EU is now putting forward? How important are these?

A: It's a progressive piece of legislation. We'll support any regulation that encourages the public provision of charging infrastructure, whether fast charge, battery switch, or standard. We're here to serve every type of plug with whatever charging mechanism the manufacturer puts in the vehicle. We're the only technology neutral network in the sense that we are the only ones who can support any charging technology a company puts in their car.

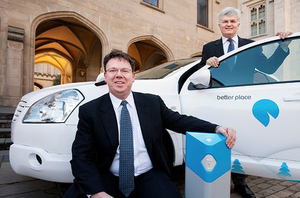

|

| Evan Thornley (left) as CEO of Better Place and University of Melbourne vice chancellor Glyn Davis (right) at a MOU signing (c) The Sydney Morning Herald |

The same is true for the proposal to standardise the plug format. You can't plug your hair dryer in across Europe right now but you really ought to be able to plug your car in. You won't always get agreement across the industry so it really is up to policymakers to stand up for the public interest: the sooner a standardised plug is adopted the better. The longer we wait the more we risk investment because we'll be worried that sooner or later we're going to have to rip out the old [infrastructure] and put in the new.

Q: What is your vision of the electric car going forward?

A: If the real purpose of what we're doing is to displace litres of gasoline from the market, then the more we focus on range extension and long-distance driving the more gasoline will get displaced. That translates into battery switch stations in part and to a lesser extent fast charge units.

Everyone shares the view that basic plug-in needs to be ubiquitous so it's a good place to start. But I think the next generation in policy development is to understand that not all cars are created equal. Taxis and delivery vans are 5-6 times more emissions-intensive than regular cars, so they are five to six times more valuable to get off gasoline or diesel. That requires range extension and as part of that you need battery switching: you can't afford to have a taxi off the road for half an hour for a fast charge, never mind 6-8 hours for a standard charge.

Q: To what extent is it the climate agenda that drives you?

A: I spent ten years in Silicon Valley and ten years in public policy. What I really like is something that is good policy and good business. Better Place is one of the few powerful environmental opportunities I've seen that makes immediate business sense. We're in the oil reduction business and there are several public policy reasons why this is a good idea: climate, air pollution and respiratory disease, and economics. For every $10 increase in the price of a barrel of oil, there's a 0.2% reduction in GDP. There is the security risk of relying on oil imports and the attraction of spending that money instead on domestic investment. Delivering mass distributed storage to the electricity grid also has massive benefits for efficient use of distribution infrastructure and for intermittent renewables generators.

The reason I left politics and went back to business is that this hits every public policy issue you can think of.

Q: What about the oft-cited argument that fewer petrol and diesel sales will severely harm national tax revenues?

A: That's an interesting discussion. Let's pull out our general equilibrium models and see what the macroeconomic impact is. We've done that exercise in Australia and it shows that the increase in efficiency in the economy more than compensates the public purse for what is lost through the reduction in gasoline taxes. At a more practical level, every practicing politician says if I can liberate people from oil, that's the biggest vote winner I've ever seen.

The problem with taxing gasoline when people have no alternative is they have no alternative. Once they

| We're in the oil reduction business and there are several public policy reasons why this is a good idea: climate, air pollution and respiratory disease, and economics |

Q: Another concern we sometimes hear is that the electricity sector will not decarbonise as planned and electric cars may therefore not cut emissions by as much as we'd like.

A: That's where you need to have the electric car infrastructure being actively supportive of renewables generators. We often hear: how do you know there will be enough renewables for all electric cars? The reality is exactly the opposite: how quickly can we get these electric cars out there because they will sponsor the development of renewables. What does a wind generator need? A volume of customers prepared to pay a premium and a solution to intermittency. Electric cars offer exactly this. They offer bulk and they are prepared to pay a premium because electricity is such a tiny part of the total cost of an electric car. Most powerfully though, our offer of mass distributed storage means we can turn intermittent supply into an effective baseload across the portfolio. This will help decarbonise the gird.

Q: Are the carmakers on board?

A: All the carmakers are trying to get higher volumes in electric vehicle production. If you take out the cost of the battery (which counts as fuel), producing an electric car is cheaper than a petrol car and certainly cheaper than a diesel car, at any given volume of production.

The problem today is that electric vehicles are produced in very low volumes versus petrol cars in very high volumes. There is a misunderstanding that electric vehicles are somehow inherently more expensive - they're actually cheaper. And the more complex emission regulations become, the more expensive the petrol- or diesel-powered train becomes because it has to do more somersaults to achieve it. The cost of ICE [internal combustion engine] power trains is going up and the cost of electric vehicles is going down. It's all about volume.

Q: What about hybrids?

A: Anything that helps hybrids drive more electric kilometres is good. If you buy a hybrid it's because you

|

Every practicing politician says if I can liberate people from oil, that's the biggest vote winner I've ever seen |

Q: So how does the long-term future look for you? Will electric cars really start to take off from 2020 as many have predicted?

A: What we know for certain is there will be an S curve. It's notoriously hard to predict when that will start and finish. My experience of new technology is that it always happens later than people think and bigger than people think. I'm ancient enough to remember working at McKinsey on mobile phones. We boldly predicted that 30% of people would have a mobile phone one day. And everyone thought we were ridiculous.

We're an infrastructure business. We have to take a long-term view. What I know is that batteries are getting cheaper, gasoline is getting more expensive and every single public policy variable is in favour of electric cars.

Discussion (0 comments)