German solar bubble? Look again!

on

German solar bubble? Look again!

A string of bankruptcies among German solar panel producers has led many to question the wisdom of Germany's renewable energy policies. However, according to energy journalist Craig Morris, the financial problems are part of a normal consolidation process taking place in the sector. He argues that a broader look at the entire value chain of the solar sector reveals that the German economy will continue to benefit from the country's role as a first mover in solar energy: "In the middle of the value chain, cell and panel manufacturers are suffering everywhere. Further down the value chain, things look much brighter."

|

| A broader look at the solar sector reveals how much Germany continues to benefit from its role as a first mover (c) Thinkstock.com |

"You ought to study Germany," Newt Gingrich stated in a TV debate on November 14, 2010 about how to compete with China. Gingrich pointed out that, like the US, Germany is a "high-cost country with a huge export manufacturing base." And Germany's economy has proven especially resilient during the current economic crisis, with 3.0% percent growth last year and unemployment at 7.0% in April.

But less than two years after Gingrich's remark, solar supporters probably wonder whether Germany still sets a good example. "The German government is running the German solar industry into destruction," Hans-Josef Fell, a chief architect of Germany's Renewable Energy Act back in 2000, told Bloomberg at the end of April. Nonetheless, Fell was speaking more as a politician than as an energy expert, for the German solar industry's woes are not the result of the current governing coalition's policies. A broader look at the sector reveals how much Germany continues to benefit from its role as a first mover.

True, Germany's Q-Cells, the largest solar cell manufacturer in the world in 2008, recently declared bankruptcy, as have a number of other smaller firms from Solon to Sovello. US solar firms, such as Evergreen Solar, have also gone bankrupt, and the biggest two solar firms from the US and Germany, First Solar and SolarWorld, are also in the red - but actually the same could be said for all of China's major solar firms, which all posted losses in 2011. Indeed, Chinese firms are in such dire straits that Suntech, the world's largest PV firm, told Reuters in May that China's PV sector might not survive if the EU follows the US's example and imposes import duties.

The problem globally is that production capacity (estimated at around 60 gigawatts) far outstrips

| The problem globally is that production capacity (estimated at around 60 gigawatts) far outstrips demand |

Germany has a trade surplus with China; the US, a trade deficit. The US exported 94 billion dollars in goods to China in 2011, compared to 367 billion in imports from China - a deficit of 273 billion. The New York Times attributed the 12.7 billion dollar surplus that Germany had with China in the 12 months leading up to August 2011 "largely [to] the sales of capital equipment that helped China produce more products." Solar production lines are one such example.

Germany benefits from solar even when panels are from China

In 2009, when competition from Chinese solar firms first raised its ugly head, there were the first timid calls for "social and environmental standards", which German firms hoped Chinese firms would not fulfill. It was a veiled attempt at protectionism, but even the German Solar Association (DGS) would have none of it: "German manufacturers have to compete with quality, longer warranties, and better service." No such requirements were ever implemented.

Two years later, when Germany's SolarWorld decided to ask for governmental help against Chinese competitors, it contacted the US government via its US subsidiary (the Department of Commerce complied). The firm probably knows what the German government would have said: nein danke, we can't afford a tradewar.

How do you define "domestic" anyway? Germany's Renewable Energy Actdoes not care whether you purchase thin-film panels made by US-based manufacturer First Solar at its plant in Germany, polycrystalline panels made by a Chinese manufacturer in China using a production line made in Germany, or monocrystalline panels made by California's Sunpower (which was taken over by French oilgiant Total in 2011) at its plant in Malaysia. Here, we see why Fell and others are wrong when they complain about cuts to the country's feed-in tariffs (FITs) hurting German manufacturers most.

|

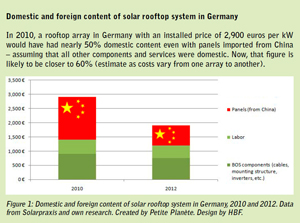

| Figure 1: Domestic and foreign content of solar rooftop system in Germany, 2010 and 2012 (c) Data from Solarpraxis and own research. Created by Petite Planète. Design by HBF. In 2010, a rooftop array in Germany with an installed price of 2,900 euros per kW would have had nearly 50% domestic content even with panels imported from China - assuming that all other components and services were domestic. Now, that figure is likely to be closer to 60% (estimate as costs vary from one array to another). |

Germany need not worry about domestic content anyway. Even if the country uses imported panels, more than 50 percent of the array's value can still be domestic. Back in 2010, a rooftop solar array would have cost around 2,900 euros per kilowatt in Germany. Berlin's Solarpraxis broke down the figures as shown in the chart above. Here, cabling, the installation substructure, and the inverter (BOS components) would probably be made locally, so nearly half of the system's value would be domestic even if the panels are from China. Today, panels from China cost closer to 700 euros per kilowatt, whereas the other prices have not dropped as much. Asa result, the share of domestic content continues to increase as (imported) panels make up than ever smaller share of the installed price.

Let us not forget the other thing that this chart shows: China has helped make solar more affordable for the world. And upstream and downstream of these manufacturers, German firms have also done a lot to bring down cost - and many of them are still doing quite well themselves.

German winners all along the value chain

The value chain for photovoltaics starts with silicon and moves on to wafers, cells, panels, and installation. In addition, there are downstream manufacturers of production lines used for wafer, cell and panel production, along with upstream array planners.

In the middle of the value chain, cell and panel manufacturers are suffering - everywhere - as explained above. For Germany, Switzerland's Bank Sarasinhas openly stated that SolarWorld might be the only

| It's consolidation, not failure. The PV sector is growing up. |

Further down the value chain, however, things look even brighter for Germany. Wacker, the largest German manufacturer of solar silicon, is now reaching full production at its new polysilicon plant in Germany and is on schedule to increase its production overall by more than 50 percent this year alone. The firm says all of its silicon is already sold up to the end of 2015, and it plans to grow by another third with a new plant in the US by 2014. Germany is also home to the world's largest inverter manufacturer, SMA, which continues to post impressive results under tough market conditions. And we haven't even mentioned Fraunhofer ISE, Europe's largest solar research institute.

German high-tech key to China's solar success

Germany has a highly competitive production equipment sector. Only around six years ago, you had to be an engineering whiz to make solar. A production line combined chemical baths from one industry with screen printers from another, with furnaces, singulation machines, flashers, etc. Some of this stuff had never been put together before.

Then came turnkey production lines around 2007. Firms like Germany's Manz, Centrotherm and Roth & Rau (along with Switzerland's Oelikon and Applied Materials of the US) started selling solar production lines that only required a Chief Technical Officer who could train staff. Q-Cells and SolarWorld bought such turnkey lines, but so did China's Trina, Suntech, etc. The shift towards China had begun.

This part of the value chain is currently also in trouble because of the massive surplus production capacity mentioned above; new production lines will be rare for a while. But this sector, too, is likely to stay in the West because it - unlike panel production - is truly high-tech, whereas panel manufacturing is not more complicated than assembling televisions and electronic devices. In other words, Germany benefits from solar manufacturing in China by selling a lot of the production equipment and getting back cheap solar panels to install.

|

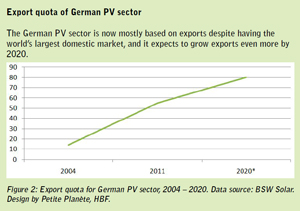

| Figure 2: Export quota for German PV sector, 2004 - 2020 (c) Data source: BSW Solar. Design by Petite Planète, HBF The German PV sector is now mostly based on exports despite having the world's largest domestic market, and it expects to grow exports even more by 2020. |

Market researchers at IMS Research recently found that the largest PV system integrator in the world is Germany's Belectric, and German firms "made up 14 of the top 30 and managed to grow their business by more than 50% to 2.2 GW." These firms are planners and builders, so they do well where a lot of solar is put on the ground and on roofs, not where solar cells are made. And the cheaper solar is, the better they do. Overall, 24 of the top 30 firms were European, and there is good news for the US as well: "U.S.-based companies First Solar, SunEdison and SunPower… were ranked 3rd, 4th and 5th respectively in 2011." Only three firms from China were in the top 30.

|

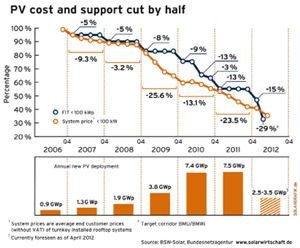

| Figure 3: PV cost and support (c) BSW Solar The price of solar power has dropped by 60 percent over the past six years. Since 2009 the German government has raced to keep its feed-in tariffs up with plummeting PV prices. While prices have come down, deployment has grown. In the last two years, Germany has installed roughly 7.5 gigawatts of additional capacity annually, making it the largest solar market in the world by far. |

In all likelihood, in 2015 Germany will still have Europe's largest solar research institute, a major solar silicon manufacturer, a leading inverter manufacturer, a number of the world's largest panel manufacturers, a few leading production equipment manufacturers, and probably the largest number of major system integrators of any country. Germany's commitment to solar will pay off - because Germany currently has the largest domestic sales market in the world.

What the US needs most: a domestic PV market

It's a good time for the US to get on board deploying solar. China and Germany have brought down the cost of solar, and the German example demonstrates that the local payback is great. Indeed, the role that Germany and China have played in helping bring down the cost of solar shows how industrialized and emerging countries can work together to deploy more renewables and combat climate change.

PV has long been cheaper than peak power for utilities and is now cheaper than the retail rate for consumers in a growing number of US states starting with Hawaii, California, and Arizona. Market researchers at McKinsey stated in April 2012 that PV will be the cheapest way for the commercial and residential sectors to get electricity in most of the US in just a few years. The future is bright indeed for solar firms that can survive the current consolidation phase.

In the US, we have to move beyond the focus on cost and insist that people be able to make their own power. While there has been a lot of talk about the level of German feed-in tariffs, not enough attention has been paid to the full name of the law: the Act on Granting Priority to Renewable Energy. As McKinsey

| The future is bright indeed for solar firms that can survive the current consolidation phase |

If the US removes such obstacles, we too will have strong system integrators, probably one or two of the world's biggest panel makers, and the US has also always been a major innovator and engineering developer in the downstream solarsector. The Center for American Progress recently pointed out that US firms can also compete with Chinese firms under free trade terms and agreed that what is needed most is domestic demand for PV.

The time is right for the US to go solar. America has been waiting for PV to become cost-competitive, and it now is. We have been talking about energy security for decades, and we have tremendous solar potential within our borders. And as an advanced industrial country, we need to remain on the innovative forefront of future technologies - and as Germany shows, solar is one.

So yea, Newt, we should look to Germany, but when we do, we won't find a country that wants to colonize the moon. If anything, Germany is colonizing the sun.

|

Protectionism and solar power Protectionism is common in policies to promote renewables. Italy offers a bonus if content comes mainly from within the EU, and former French Prime Minister Sarkozy considered doing the same. In Canada, Ontario - the leading province for renewables - has also always had a provision for domestic content in its Green Energy Act, but things are even worse in Ontario because "domestic" is defined as coming from the province itself, not from Canada. In the US, a slew of states require domestic content, meaning that one state will even discriminate against another just as Ontario discriminates against other Canadian provinces. For instance, the state of Washington pays 36 cents per kilowatt-hour of solar power from small arrays with in-state panels, but only half as much - 18 cents per kilowatt-hour - if the panels were made in Oregon by SolarWorld (Germany's largest solar panel manufacturer) or in China by Suntech (the largest Chinese manufacturer). Maddeningly, Washington is not really much of an exception here; often, no distinction is made between foreign and "out of state." |

|

About the author Craig Morris is an American writer and translator in the energy sector who has been based in Germany since 1992. He directs Petite Planète and writes regularly for Renewables International. |

Discussion (0 comments)