The Russo-Ukrainian crisis : possible gas scenarios

on

The Russo-Ukrainian crisis: possible gas scenarios

While no-one doubts Russia can militarily conquer Crimea and hold on to it, Ukraine and its allies have economic options in this conflict that mainly relate to the energy sector. The speed at which events unfold would make a prognosis of the conflict itself obsolete within days. However, Energy Trading and Risk management consultant Michael Grossmann reviews plausible actions by all the conflict's stake-holders affecting the gas flows within Russia, Europe and the Black Sea basin.

|

| (c) Igor Golovniov |

Dialling down Russian gas flow through Ukraine

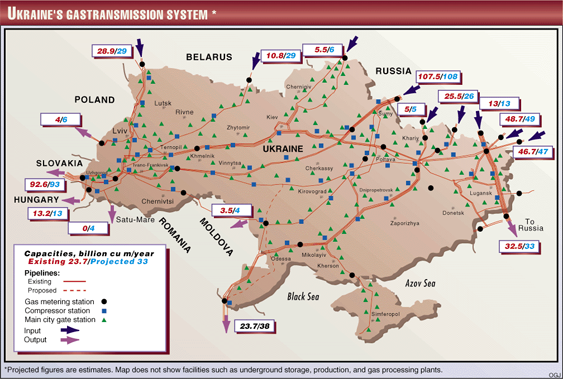

Restricting the gas flow would be easy, because the Soviet-era gas export pipelines converge near Uzhgorod, in the fiercely anti-Russian far West of Ukraine. While Ukraine's embattled acting government might want to hold back from this measure, if the military situation extends beyond Crimea or if the occupation drags on, sabotage by Ukrainian nationalists cannot be excluded. About 80 billion cubic meters (bcm) of the 162 bcm of gas that Gazprom exports to Europe transits through Ukraine.

| A disruption of the Ukrainian transit link would also internationalize the conflict because Europe depends on Russia for one quarter of its natural gas supply |

Countering this, Western Europe has the capacity to import up to 190 bcm equivalent of Liquefied Natural Gas [note 1]. LNG being generally more expensive than piped gas, only 41 bcm was imported as LNG in 2012. This said, LNG imports could not substitute lost Russian gas supplies for Germany or Eastern Europe. These countries do not have LNG terminals of their own at time of writing, and westward gas flows cannot be reversed over long distances. The effect on the global LNG market would be immediate, and far more important than the Fukushima nuclear meltdown. On the longer term, the European security of supply imperative would give an impetus to the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline, which is meant to ship up to 10 bcm annually from the Caspian Sea to Italy [note 2]. Another EU-supported project, which was quietly shelved in mid-2013, might be revived. The Nabucco pipeline project, which shares the same route up to Turkey, would enter Europe in Bulgaria and join Austria. Perhaps under adversity will Europe finally become as assertive in its external energy policy as it has been in its internal market.

|

| source: www.outsidethebeltway.com |

Russia's non-military options

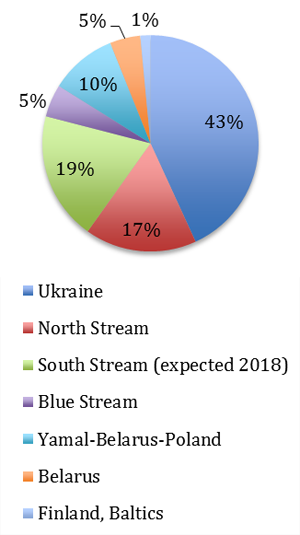

Ukraine is unlikely to pay Russia for its gas consumption while the confrontation lasts, and Russia may in turn feel justified in cutting or reducing the gas flow. Whether it is Russia's or Ukraine's doing, Gazprom will bear the economic consequences. The Russian gas giant is the source of 25 percent of the Russian state's revenues, which stood at almost 56 $ billion in 2012 [note 3]. For the longer term, there is not much Russia can do that it has not already started to do to circumvent Ukraine in exporting gas to Europe. This is the result of the Russo-Ukrainian gas spats in 2006 and 2009. While Nord Stream may have had some economic justification when it was initiated, it is operating at less than 30 percent of its capacity of 55 bcm [note 4], and talk of future capacity expansion now seems far-fetched. Gazprom's gas has become uncompetitive because it has remained largely oil-indexed. As a result it has lost market share to Norway's Statoil, and this trend is likely to continue as Gazprom's long-term contracts come to expiration. The economic case of South Stream was never clear, and now it looks like a futile geopolitically move expected to cost Gazprom between $60 b and $85 b, including the new pipelines from Yamal to the Black Sea [article Moscow Times]. For one, it is planned to become operational in 2018, probably too late to make an impact on the current conflict. Secondly, Gazprom might not have the gas volumes to match the nameplate capacities of both Nord and South Stream. Gazprom's pipelines, including Nord Stream have capacity in excess of its historical peak production of 170 bcm in 2013; thirdly, it may fall foul to the EU's internal gas market laws, which require that gas supply and pipeline operations be separated (the "Third Party Access" or TPA clause of EU gas market rules). Nord Stream is a direct undersea link between Russia and Germany and might not be subject to TPA. South Stream is a different matter. It crosses four countries before reaching Italy. The EU may impose its access rules and regulate its tariffs after all.

Pivot to Asia

Stalling natural gas demand in Europe, EU gas market rules, the topographic complexity and expense of reaching markets while avoiding troublesome transit countries, all of this should have incited Russia to develop its LNG export capacity as a matter of priority over pipelines to Europe. The current conflict might trigger a Russian pivot to Asia, not unlike the US's under Obama's presidency. On 1 December 2013, a law authorized companies in which the state has a stake of at least 50 percent to invest in LNG export terminals [note 5]. Novatek and Rosneft are the beneficiaries of this law, which means that they can now compete with Gazprom in exporting LNG from Russia.

| The current conflict might trigger a Russian pivot to Asia, not unlike the US's under Obama's presidency |

|

| transit capacity (bcm/yr) |

A ramp-up of LNG from the US

The growth in the US's natural gas production following the unconventional gas revolution has freed large amounts of previously contracted LNG. While some of it has been bought by Japan following the Fukushima catastrophe, LNG is increasingly available as a spot commodity in the Atlantic. In its 2014 reference scenario published in December 2013, the US Energy Information Agency saw US LNG exports rising from nothing currently to 100 bcm / yr by 2029. In case of a gas shortage in Europe, the US's Department of Energy would accelerate the authorization process for new LNG export terminals, both out of economic opportunism, and out of strategic considerations. Most of these terminals are sited on the Atlantic coast, and are therefore well-suited to supply Europe.

Possible repercussions across the Black Sea

One temporary equilibrium state is likely to emerge because it would satisfy the West's desire to avoid a wider conflict, and satisfy Russia's exacerbated nationalism: Russia could hold on to Crimea indefinitely, recognizing its "independence". It would in the process ensure a long-term lease on the naval base of Sebastopol. A military intervention in eastern Ukraine "at the demand of" local sympathizers cannot be excluded either. Unlike the other frozen conflicts however, this is not tenable indefinitely for Russia. At the time of writing, Europe's response so far has been threats to halt the negotiations on easing the visa regime for Russian citizens and not participating to the G8 summit, which is scheduled to be held in Moscow and Sochi during March 2014. A likely next step would be targeted visa sanctions against rich and powerful individuals close to the Kremlin.

The Russo-Ukrainian conflict could also go international via Turkey. Crimea's 250,000 Tartars are one of the peninsula's historical inhabitants. Following Crimea's integration in the Russian empire in the XVIIIth century, Russians are now the main ethnic group, with 1,180,000 inhabitants. The Tartars were allies of the Ottoman Empire, which they provided with slaves. Tartars in turn were massively deported to Central Asia during WWII. Whatever the historical antagonism between Tartars and Russians, Crimean Tartars are squarely on the side of a sovereign Ukraine because they do not want to be living in a Russian military colony. Since the breakup of the Soviet Union, Turkey has developed cultural and economic ties with the Turkic people of the Caucasus and Central Asia. Following the Armenian-Azerbaijan war over Nagorno-Karabakh of 1992, Turkey imposed a trade blockade to Armenia in support of its Azeri brethren. The blockade continues to this day. Turkey's authoritarian prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdoðan, might seize the opportunity to distract attention from corruption scandals and pro-liberal contestation at home, to champion the Tartars. Clearly Russia is a more imposing military presence than Armenia, but Turkey could impose restrictions on navigation through the Bosphorus Straights "to relieve congestion". The 1936 Montreux Convention gives Turkey full control over the Straits and guarantees the free passage of civilian vessels in peacetime. Throughout the Cold War, the Straights were left open and the Soviet Black Sea fleet could sail into the Mediterranean.

As with Europe, the economic costs would be asymmetrical. Turkey received 14 bcm of gas in 2013 through a Russian pipeline that passes through Ukraine, and 16 bcm from Russia directly by the Blue Stream pipeline beneath the Black Sea, out of a consumption of 45 bcm. Turkey represents fully 19 percent of Russia's gas exports. Turkey has in the past taken steps to diversify its gas supplies, by purchasing LNG from Algeria, and piped gas from Azerbaijan and Iran.

Biggest loser of all

A disruption of natural gas and other trade flows would be costly for all parties involved. Whether gas flows are curtailed, strategically at Russia's initiative, as an act of Ukrainian retaliation, or even as a self-imposed reduction in imports in Europe, European consumers would be the first to be affected through price hikes. On the short term, importing nations would have to purchase suddenly expensive spot LNG; at the time of writing, European gas market hubs are reaching peaks of liquidity as consumers try to hedge their price exposure. On the longer term however, Russia would be the clear economic loser. After having invested in two costly offshore pipeline projects to guarantee "security of gas supply" for Europe, it would be ironically the one to single-handedly destabilize gas supply, and ruin the reputation of a reliable supplier since the eighties during the formative years of Europe's gas market.

- Gas Infrastructure Europe, January 2014

- The route covers Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey, Greece, Albania and ends in Italy. It is supported by Statoil of Norway, together with Axpo of Switzerland, and E.ON of Germany.

- The Economist, 23 May 2013, Gazprom, Russia’s wounded giant

- In its final form, it was inaugurated in April 2012.

- Russian LNG: the long road to export, Tatiana Mitrova, December 2013

- Gazprom - 50%, ExxonMobil - 27.5% minus 1 share, remainder with Mutsubishi and Mitsui

- Russia's Novatek - 60%, French Total - 20%, Chinese CNPC – 20%)

Discussion (0 comments)