The UK's road to a green future: paved with good intentions - but will the lights stay on?

on

The UK’s road to a green future: paved with good intentions - but will the lights stay on?

When it comes to enacting policy for a transition to a sustainable energy future, the UK is a world leader. Already enshrined in law are legally binding targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 80% from 1990 levels by 2050, with stepping stone targets along the way to cut them by half by 2027. In every carbon-emitting sector the UK has set out specific policies to help meet these targets, especially the crucial electricity generation sector which is the biggest contributor – and getting bigger. But how realistic will these good intentions turn out to be? There are some who fear that the determination to decarbonise over the long term could lead to an energy crunch in the UK before the end of this decade.

|

| Green Union Jack (c) TriplePundit |

Thanks to the Climate Change Act – which set ambitious and legally binding targets for greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions up to 2050 – the UK's efforts to make a transition to a sustainable low-carbon energy economy have maintained impressive momentum. Elsewhere, especially in recession-buffeted continental Europe, climate change concerns have tended to slip down the political agenda, in favour of more pressing economic concerns.

“Coherence and commitment”

The UK’s decarbonisation ambitions were recognised last year by the International Energy Agency, which from time to time reviews the energy policies of its member countries. Its report on UK policy said: “The UK has defined a strategy to move to a low-carbon economy and to tackle climate change with a remarkable sense of coherence and commitment.”

While the Climate Change Act was enacted by a Labour government, the political momentum it imparted to climate policy survived the general election of May 2010, when a coalition of Conservatives and Liberal Democrats –

| The UK's Climate Change Act of 2008 was a remarkable piece of legislation - not least in its timing |

“Even in these tough times, moving to a low-carbon economy is the right thing to do, for our economy, our society and the planet. This plan sets out how coalition government policies put us on track to meet our long-term commitments. The Green Deal will help cut energy bills, the Green Investment Bank will attract new investment, and our reforms to the electricity market will generate jobs in new low-carbon industries.”

More recently, in a speech in London in February, Cameron once again stressed his commitment to meeting the ambitious targets in the Climate Change Act, not just because it is “right for our planet” but because it is “right for our economy too” – arguing that “it is the countries that prioritise green energy that will secure the biggest share of jobs and growth in a global low-carbon sector set to be worth $4 trillion by 2015”.

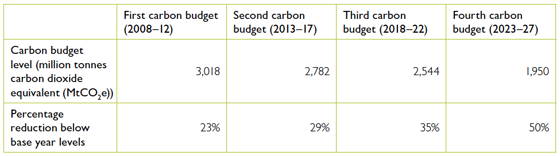

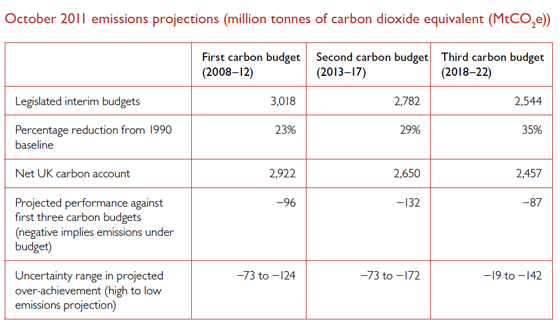

On budget

The UK has already chalked up significant achievements in reducing its GHG emissions, which are down by more than a quarter since 1990. As chart 1 shows, this means that the UK has already met the first of three five-year carbon budgets set in law in 2009, that together require GHGs to be cut to 35% below 1990 levels by 2022. Moreover, as chart 2 shows, government projections indicate that all three targets are likely to be exceeded.

|

| Chart 1 - Shows the limits on greenhouse gas emissions set by the Climate Change Act 2008 for the first four budget periods. The fourth carbon budget, if achieved, would see emissions reduced to 50% of 1990 levels by 2027 – a very ambitious target. |

|

| Chart 2 - Shows that, as of 2011, the UK was projecting that it would exceed its targets for the first three carbon budgets, which run to 2022. |

That said, a fourth carbon budget set in law in 2011 looks rather more challenging, setting as it does a target for emissions to be cut to 50% below 1990 levels by 2027. “This,” says the government in its Carbon Plan, “will put the UK on a path towards an 80% reduction by 2050.” In other words, it would put the UK on a trajectory towards meeting not just the headline target of an 80% cut by 2050 set out in the Climate Change Act, but also the target range of 80-95% by 2050 endorsed by European Union leaders.

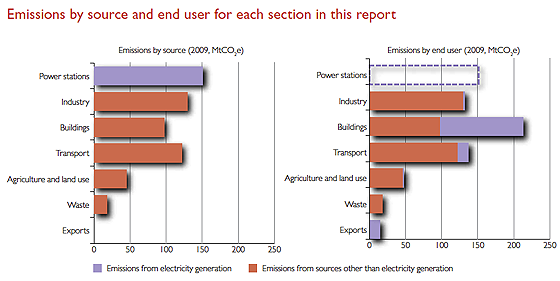

Progress has been made in all of the carbon-emitting sectors that the government has defined in its policies: power stations, industry, buildings, transport, agriculture and land use, and waste. Chart 3 show UK GHG emissions by source and by end-user sectors in 2009, in millions of tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e).

|

| Chart 3 - shows that in 2009 electricity was the largest emitter of GHGs, with buildings accounting for most of the electricity consumed. Electricity is expected to grow its share as energy consumption shifts towards electrification from other primary fuels. Therefore, the UK’s policies around the decarbonisation of electricity generation will be critical to the UK meeting its 2027 and 2050 targets. Source: DECC National Statistics |

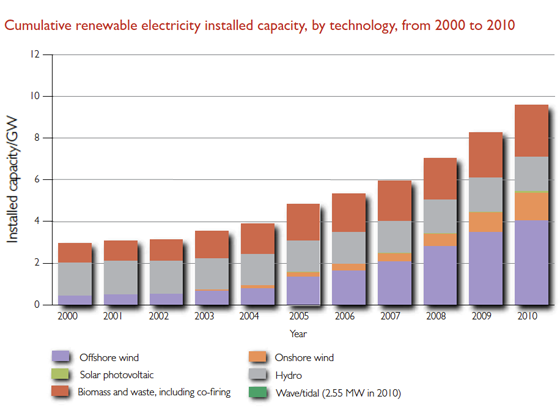

Emissions from power stations fell by almost a quarter between 1990 and 2010, partly because the “dash-for-gas” of the 1990s saw large numbers of coal-fired power stations replaced by gas plant, and partly because wind and other renewables have grown over the past decade to supply nearly a tenth of UK generating capacity - see Chart 4. With nuclear power generating some 16% of the nation’s electricity, a quarter of total UK electricity is now low-carbon.

|

| Chart 4 - shows the – impressive – progress made in installing renewable energy capacity by technology from 2000 to 2010. Offshore and onshore wind accounts for more than half the 10 GW total reached by 2010. |

Emissions accounted for by buildings have fallen by 18% despite growth in population and housing. In transport, emissions rose from 1990 until 2007 as transport demand increased but have since fallen back to around 1990 levels, partly because vehicles are becoming more efficient, partly because of the increasing use of biofuels, and partly because of the economic downturn.

Industrial emissions have fallen by 46% since 1990, despite output growth of around 1%/year, as industry has become more energy-efficient and as the industrial base has shifted to less energy-intensive activities. Agricultural emissions are down by almost a third, thanks partly to more efficient farming. Meanwhile, diversion of waste from landfill has led to waste emissions falling by two-thirds.

The road ahead

So far, so good. There are, however, big challenges and uncertainties ahead. Despite the progress to date, meeting the target in the fourth carbon budget, a 50% reduction from 1990 levels by 2027, and the 2050 target of an 80% reduction, will require nothing short of a revolution in how the UK generates and uses energy.

The biggest challenge is likely to be decarbonising the electricity sector, not only because it is currently the largest contributor to GHG emissions, around 27% of the total, but also because improvements in other sectors will come in part from increasing electrification of heating, industrial processes and transport. The government estimates that between 40 GW and 70 GW of new low-carbon electricity generation capacity will need to be deployed by 2030.

By 2050 average electricity demand may rise by between 30% and 60%, meaning that the UK may need to double its generation capacity to handle demand peaks. Moreover, emissions from the electricity generation sector will need to fall to close to zero. It looks a tall order.

The government has pinned its hopes on three low-carbon electricity generation technologies: a new generation of nuclear power stations;

| “This”, says the government in its Carbon Plan, “will put the UK on a path towards an 80% reduction by 2050”. |

Progress towards a new generation of nuclear power stations has been slower than was hoped when the Climate Change Act was passed. Back then it was expected that the first new nuclear power station would be on stream in 2017. It now looks unlikely than any new nuclear stations will be operating in the UK until well into the 2020s – if then.

EDF recently received consent for the first proposed new nuclear power station – made up of two 1.6 GW reactors at Hinkley Point in Somerset – but its partner Centrica pulled out in February. Meanwhile, negotiations currently under way with the government on the price that nuclear power can rely on for its contribution to the nation’s electricity needs have been going on for much longer than expected. The government recently published “strike prices” for a range of renewable energy sources but a price for nuclear was noticeably absent.

Renewable electricity generation capacity will continue to grow – but so will the issue of intermittency. A report recently published by the Climate Change Committee (CCC), a body established by the Climate Change Act to advise the government on policy, argues that even a high degree of intermittency should be manageable. However, it acknowledges that substantial gas-fired generation capacity will be needed to provide back-up when the wind doesn’t blow.

Not proven

And because natural gas is a fossil fuel, and therefore a contributor to carbon emissions, its continued use to 2050 will depend on the successful commercialisation of CCS. This is where the government’s strategy looks least robust. CCS has yet to be proved commercially, anywhere in the world, in the context of power generation.

Here too the UK is a world leader. The government recently announced that it had selected two projects to be supported under its £1 billion CCS commercialisation programme: a gas post-combustion project at Peterhead and a coal oxy-fuel project at Drax. These projects will now proceed with front-end engineering and design (FEED), with a view to taking final investment decisions by early 2015.

Nevertheless, hopes that 10-15 GW of CCS-aided electricity generation capacity will be built in the UK by 2030 are surrounded by a high degree of uncertainty. Indeed, it remains to be seen whether CCS will ever be economic on the scale required to contribute significantly to climate change mitigation – in the UK or anywhere else.

In a report published a few weeks ago,

| Moreover, emissions from the electricity generation sector will need to fall to close to zero. It looks a tall order |

Electricity market reform

Right now in the UK, a particular focus of attention is electricity market reform (EMR), a major part of the energy bill currently wending its way through parliament. The government sees this legislation as the most important step in its strategy for decarbonisation of the electricity generation sector, but it has proved to be highly controversial.

Four major reforms have been proposed to address the difficulties faced by potential investors in low-carbon generation:

- A carbon price floor is proposed because the carbon price under the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) has been too low to encourage sufficient investment in low-carbon generation.

- New long-term contracts are to be introduced – known as feed-in tariffs with Contracts for Difference (CfD) – to provide stable prices for low-carbon electricity generation. Essentially , these contracts will fix the amount of money that generators receive per unit of electricity at a price known as the “strike price” (with different prices for different forms of low-carbon electricity generation).

- A capacity market is to be introduced to ensure that sufficient capacity is available, especially during peak demand periods, as the proportion of inflexible and intermittent low-carbon generation grows. This will involve contracts for generation, demand-side response and storage, which will be managed though a central auction process.

- An emissions performance standard is to be set at 450 gCO2/kWh to ensure that no new coal-fired power stations are built without CCS.

The government is adamant that the EMR policies, along with others in the energy bill, will “attract the £110 billion investment that is needed to ensure that the UK can meet its requirements for secure and flexible supplies of electricity at affordable prices”.

However, in recent months a number of high-profile figures in the energy industry – including Alastair Buchanan, the head of energy regulator Ofgem; Ian Marchant, chief executive of SSE, one of the UK’s “big six” energy suppliers; and Sir Roger Carr, chairman of Centrica, another of the big six, and president of the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) – have been warning that the UK faces a serious threat of the lights going out later in this decade.

“Critical juncture”

How has it come to this? In the government’s own words: “The UK is at a critical juncture in the way it generates electricity. Around a fifth of capacity available in 2011 is set to close over the coming decade.” This is partly because some nuclear power stations are reaching the end of their working lives and partly because some coal-fired power stations are having to close because of environmental legislation.

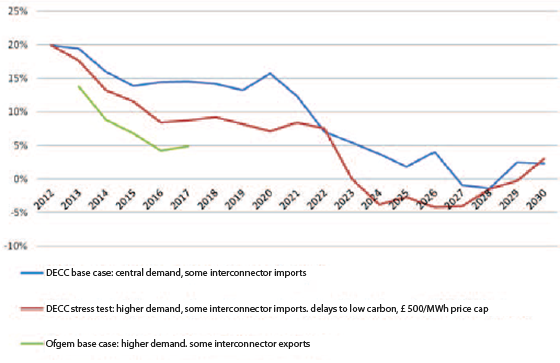

Unfortunately, expected investments in alternatives, low-carbon or otherwise, have been slow to materialise, with the consequence that the capacity margin – the difference between generating capacity and peak demand – is expected to fall to worryingly low levels in the second half of this decade and beyond (see chart 5). Potential investors in new generation are therefore urging the government to resolve the uncertainty hanging over energy policy as quickly as possible.

|

| Chart 5 - shows modelling of the capacity margin (difference between available generation and peak demand) by the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) and energy regulator Ofgem. Note that in the Ofgem modelling the margin is projected to fall to below 5% - a worryingly low figure in terms of supply security. |

Even the Climate Change Committee is warning that “the current high degree of uncertainty about development of the power system beyond 2020 threatens fundamentally to undermine the EMR.”

Other measures put forward by the government to decarbonise the UK’s energy economy have proved much less controversial. The Green Deal, which aims to encourage households and businesses to invest in energy efficiency measures by allowing the costs to be paid over time through energy bills, has been welcomed with enthusiasm. It is a central plank of the government’s efforts to reduce GHG emissions from buildings. Widespread introduction of smart meters as a prerequisite to the development of smart grids has also been welcomed without fuss. It is in electricity that the government faces a big test.

The immediate challenge for the government is to get through the next few years without the UK going through an energy crisis – without, as the common parlance has it, “the lights going out”. That would discredit not just the government but also the whole of the UK’s bold decarbonisation strategy.

Discussion (0 comments)