The growing role of Turkey in the EU’s security of energy supply

on

The growing role of Turkey in the EU’s security of energy supply

Turkey is dedicated to playing a driving and constructive role in the timely, reliable, cost-effective and environmentally responsible transportation of Caspian, Middle Eastern and Central Asian hydrocarbon resources to European and world markets. To this end Turkey is doing all it can to develop new projects which will enhance its own energy security and those of its partner countries, as well as to bolster prosperity and peace in the region and the world. In this context, Turkey’s accession process to the EU is of great significance. With its dynamic energy market, its rapidly modernizing energy infrastructure, its developed regulatory framework and unique geographical location, Turkey as a EU member could contribute significantly to the energy security of the EU and Europe as a whole.

|

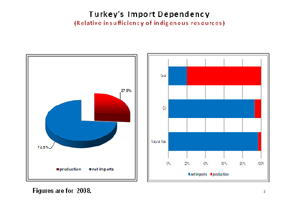

| Turkey's import dependency |

Turkey’s domestic primary energy sources are highly limited. As of 2009, only some 24% of total energy demand was met by domestic resources while the rest was supplied from a diversified portfolio of imports. Natural gas, virtually all of which is imported, already has a share of one-third in Turkey’s total energy consumption.

Diversification of imports in terms of sources, routes and technologies has long been an important policy tool for Turkey to improve its energy security. Turkey has already achieved diversification to some extent in its gas supplies, evidenced by the growing number of pipelines and LNG options that it has. However, there is a need for further diversification in terms of source country, as some 62% of the country’s natural gas imports come from the Russian Federation.

In recent years, Turkey has also concentrated on increasing the use of its indigenous energy resources in a cost-effective manner. Policymakers believe that ensuring larger shares for renewable and nuclear energy in the country’s energy mix will make it possible to diminish the share of natural gas. Hence, Turkey’s energy strategies related to renewable and nuclear energy impact directly on the natural gas market.

In the regulatory sphere, Turkey has embarked on a policy aiming at comprehensive liberalization and the establishment of a competitive energy market with an investor-friendly environment. Since 2001, Electricity, Natural Gas, Petroleum and LPG Market Laws have been enacted to enforce private sector involvement under independent regulation and supervision. However, there are still a number of challenges to be tackled, particularly with respect to the competitiveness of the natural gas market. To address this particular problem, Turkey aims to develop a sound investment environment based on competitive market principles congruent with EU legislation.

Natural corridor

Geographically located in close proximity to around 72% of the world’s proven gas and oil reserves, in particular those in the Middle East, the Caspian basin and Central Asia, Turkey forms a natural energy corridor between important producing countries and big consumer markets. Thus it stands as a key country in ensuring global energy security through the diversification of supply sources and routes. In its energy strategy Turkey attaches great significance to undertaking this energy corridor role between producer and consumer markets. The country aims to be a regional energy trading hub.

|

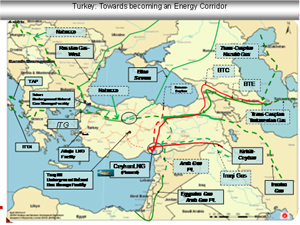

| Turkey: towards becoming an energy corridor |

Turkey has elaborated the East-West Energy Corridor concept in cooperation with its partners and neighbours to help diversify the energy supply routes for the transportation of Caspian hydrocarbon resources. The pioneering project has been the 1800 km long Baku-Tblisi-Ceyhan (BTC) crude oil pipeline, which has been in successful operation since May 2006. It has a capacity of 50 million tonnes per year or 1 million barrels per day.

The Kerkuk-Ceyhan Crude Oil Pipeline, designed to transport Iraqi oil to Ceyhan, started operation in 1976. The pipeline is owned and operated by BOTAS, the Turkish state-owned corporation. A second parallel pipeline was completed in 1987, reaching a total capacity of 70.9 million tonnes per annum. The Intergovernmental Agreement between Iraq and Turkey underlying the pipeline was renewed and extended for 15 years on 19 September 2010 in Baghdad.

Reducing the risks

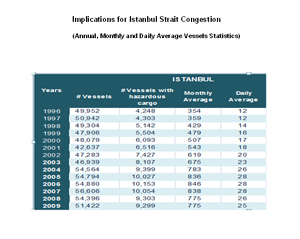

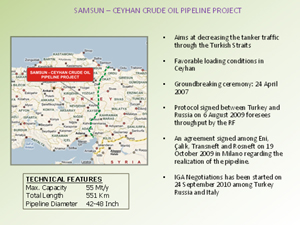

Turkey recognizes of course the importance of the Turkish Straits for global energy supply security. It fully respects the international treaties that regulate free trade conditions through the Turkish Straits. But the dense shipping traffic that the Straits experience on a daily basis forces Turkey to consider alternative ways for energy transportation. The growth in hydrocarbon exports via the Black Sea has turned the Turkish Straits into a tanker highway, which has led to public concern. With the total number of vessels passing through the Istanbul Strait reaching a peak in 2007 with 56,606 vessels, experts say that the limits have been reached. Further growth would lead to unacceptable risks. As the volume of crude oil and other hazardous cargo expected to be transported through the Straits is only expected to grow, Turkey wants to reduce the risks by shifting export routes from the Turkish Straits to pipelines.

|

| Implications for Istanbul Strait Congestion |

Regarding natural gas supply, the Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum (BTE) natural gas pipeline Project has taken on a vital role. The pipeline, with a capacity of 11 billion cubic metres per annum (bcma), was designed to deliver gas from the giant Shah Deniz field in Azerbaijan to Turkey and has been operative since July 2007.

For gas deliveries to Europe via Turkey, two important projects have been undertaken so far. The first project, the Turkey-Greece Natural Gas Pipeline, which starts in Erzurum, is one of the strategic expansion projects towards Europe which is planned to be extended up to Italy. The 296 km long Turkey-Greece Interconnector (TGI) has been in operation since November 2007. In October, 2009, a “Joint Declaration” was signed between Turkey and Italy to extend the pipeline to Italy. Both countries reiterated their political support for the project. The ITGI (Italian-Turkey-Greece Interconnector) is expected to be ready in 2016 and will have a capacity of 12 bcma.

|

| Samsun - Ceyhan crude oil pipeline project |

Furthermore, Turkey gives its support to the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) Project, in line with its policy of enhancing the energy security of EU countries. With regard to TAP, a Memorandum of Understanding on Energy Cooperation including gas transit was signed in November 2009 between Turkey and Switzerland. Swiss company EGL is one of the major shareholders in TAP.

Thus, Turkey has expressed its support for all three EU pipeline projects which are currently competing with each other to source oil. It has signed all the relevant official documents and has not displayed any preference officially for one or the other of the projects. However, Nabucco has more than mere official support, as state-owned corporation Botas is one of the shareholders in this project.

|

| TAP, ITIG and Nabucco |

Similarly, Turkmenistan has good prospects to increase production. Ensuring gas flows from Turkmenistan through the Caspian Sea has long been attracting interest from policy makers and companies in Turkey. Various alternatives are being studied to bring into existence a Trans-Caspian gas flow.

More effective

The pipeline projects linking the Caucasus, Central Asia, and the Middle East to Europe will make a substantial contribution to the region’s integration with the West. Secure and commercially profitable pipelines will help enhance stability and prosperity in the region. Considering the system as a whole, and to make it more effective, Turkey aims also to increase its natural gas storage capacity. The Silivri underground storage facility (with a capacity of 2.2 bcm) located at the north shore of the Marmara Sea was taken into service in 2007. New underground storage projects have also been developed recently both by the state-owned Turkish pipeline company BOTAS and by a private sector company in the Tuz Golu basin in Central Anatolia.

Then there is the Arab Natural Gas Pipeline project, which foresees transportation of Egyptian gas via Jordan, Lebanon and Syria to Turkey and onwards to Europe. The pipeline has reached Homs in Syria and Jordan, Lebanon and Syria have begun to receive Egyptian gas. The construction of the remaining part between Homs (Syria) and Turkoglu (Turkey) has not been completed due to lack of supply commitment from the Egyptian side.

|

For Iraq, the prospect of its gas reaching European markets seems both a desirable and achievable objective. In fact Iraqi political authorities have already expressed their interest in the Nabucco project. Turkey considers Iraq’s participation in Nabucco an essential ingredient to its succes. Iraq is not only one of the main potential gas providers but Turkey also hopes that increased gas exports can make a contribution to the improvement of the political stability of the country and of the region in general.

Analysts expect demand for gas to continue to grow both in consumers’ markets but also in producing countries. Some analyses show that within 20-25 years some of the gas exporting countries will turn into net importing countries. Hence, from the point of view of security of supply, Turkey considers it is important in the long run to involve Iran into the equation. Alleviation of the tension in the relationship between the Iran and US governments could pave the way for a fruitful atmosphere which would enable Iran to become a part of the solution.

Electrical interconnection

With regard to electricity infrastructure, Turkey aims to fully utilise its indigenous hard coal and lignite reserves, its hydropower and other renewable resources such as wind and solar energy. This is necessary in order to meet the rapidly growing electricity demand in Turkey in a sustainable manner. The integration of nuclear energy into the energy mix will also be an important contribution to meet growing electricity demand while avoiding increasing dependence on imported fuels.

For the construction of a first – very large – nuclear power plant, which will consist of four units of 1200 MW each and will be built with Russian technology in Akkuyu (Mersin), on the Mediterranian shore, an Intergovernmental Agreement has been signed between Turkey and Russia. The power plant will initially be owned 100 percent by Russian companies. Turkey provides a purchase guarantee at a certain price ($12.35 per kWh) for the electricity generated by the power plant for fifteen years.

A second nuclear power plant is planned on the shore of the Black Sea (in the Sinop region), in which Japanese companies might be involved. Turkey and Japan have reached an agreement-in-principle on this. More detailed negotiations have just been started and are expected to be completed within 3-4 months.

|

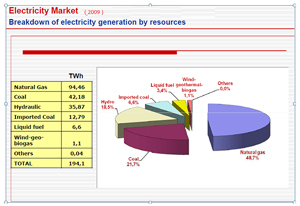

| Breakdown of electricity generation by resources |

Another important project in this regard is that of the Mediterranean Ring or MEDRING. The MEDRING, which is listed as a “Priority Project” by the EU, envisages electrical interconnection among all the countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea. Some technical studies have been performed but more needs to be done. Following the execution of further studies, the interconnection of the power grids of the countries in North Africa and South Europe can be realised and electricity trade will be initiated.

All these regional energy projects in which Turkey is an active participant, will open up new avenues for cooperation between the countries in the region and reinforce the ties between Europe and Asia. Building on those achievements, Turkey will continue its efforts to contribute significantly to global energy security.

| Yusuf Yazar (yyazar@enerji.gov.tr) is Deputy Undersecretary at the Turkish Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources. He obtained a B.S. degree in engineering from Yildiz University, Istanbul in 1977. He received his MS degree in geodetic surveying from Kandilli Observatory and Earth¬quake Research Center at Bogaziçi University, Istanbul. Intermittently until 1988 he worked as an engineer at several construction and civil engineering projects both in Turkey and abroad. From 1988 to 2003, he served as a lecturer at the Engineering Faculty in Anadolu University and Osmangazi University (both are in Eskisehir, Turkey). Since the early 1980s he contributed to several journals writing mostly on international relations. In 2003, he was assigned to the Energy Market Regulatory Authority as Advisor to the President. Since February 2004 he occupies the position of Deputy Undersecretary. The views in this paper are the author’s personal opinions; they do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Turkish government. |

Discussion (0 comments)