The new 'old' Energy Union initiative

on

United in diversity - to what extent?

The new ‘old’ Energy Union initiative

Describing the status quo in the EU energy sector may seem like an attempt to draw a moving train: the combination of internal EU policy initiatives set in motion together with external geopolitical changes, entail some significant transformations for the European energy world.

|

| Source: acdemocracy.org |

Against this background, the IX Energy Forum held in Poland on 22-24 January 2015 sought to address some key issues for the European energy sector with the focus on the Central and Easter European (CEE) countries. Security of supply and the future of the European Energy Union were, undoubtedly, among the most debated ones. Before illuminating the discussion in the region, it seems necessary to develop on the current status of conceptualizing the Energy Union and its roots. This would be a good starting point to bring together the exact elements of this new initiative.

Paraphrasing Kissinger, if one asks ‘Who do I call if I want to call Europe … and talk energy?’

| Who do I call if I want to call Europe … and talk energy? |

The backdrop of the geopolitical tensions at the EU borders, impetus from the European Council, endorsement of the 2030 energy package and appointment of the new Commission created a momentum for the establishment of the new EU initiative – the Energy Union. The goal ‘to build the Energy Union with a forward-looking climate policy’ was formulated by the European Council in the Strategic Agenda for Europe in Times of Change (European Council 26/27 June 2014, Conclusions). However, the idea itself is not new at all, although the wording is. Jerzy Buzek and Jacques Delors have been some of the most active proponents of creating ‘a new European Energy Community’, which in turn, draws on the inception of the EU that started with cooperation in the field of energy (European Coal and Steal Community and Euratom).

Historically, due to the characteristics of the sector: capital intensity, long-term investment cycles and risks adherent to it, energy companies have been considered ‘natural monopolies’, therefore the challenges that the EU has been facing with the liberalisation of the sector are, to a certain extent, unavoidable (not to mention the differences in EU member-states’ energy mixes and the legacy of infrastructural choices– which in the case of EU-Russia gas relations has been developing over 40 years of energy trading between the two).

Over the past years, liberalising energy markets, improving energy interconnection and protecting the environment, while acting in the spirit of solidarity has been indeed high on the EU agenda .

| EU’s energy policy has often been reactive rather than proactive |

The Energy Union is being positioned as the key enabler for achieving the 2030 objectives of the EU, while taking stock of the outcomes from the 2020 framework and improving the coordination between the three energy targets. The political and economic environment today is certainly different from the one in 2007 when the 2020 framework was endorsed. Although the concerns over the climate change remain, the financial crisis of 2008, slowdown in economic growth, as well as the challenge of competitiveness of the EU industries, coupled with a perfect storm in the electricity sector due to expansion of RES with subsidies and national interventions, and ultimately the collapse of carbon prices, create a completely different environment for tackling the EU energy trilemma.

Keeping a lead on the world’s battle against climate change is certainly an important task for the EU as well, however, another question that remains is to what extent the countries outside the Union would be on board (EU currently accounts or only 20% of worlds CO2 emission). The upcoming UNFCCC Conference in Paris will certainly be an important milestone in addressing this issue and set the agenda for the coming years

To sum up, the Energy Union is expected to have five dimensions:

- Supply security based on solidarity and trust: exploring the possibility of establishing a common gas purchasing system and obligations regarding gas reserves; diversifying supplies and strengthening the Energy Community; increasing energy efficiency and the use of domestic energy sources; pursuing coherent energy diplomacy;

- A competitive and completed internal energy market with focus on regional cooperation and integration – finalizing the adoption of electricity and gas network codes, accelerating the development of electricity and gas interconnectors (through the PCI and CEF framework, as well as Junker’s investment Plan);

- Moderation of energy demand review of the framework laws on energy efficiency, energy performance of buildings, energy labelling and eco-design, as well as vehicle CO2 standards regulation.

- Decarbonisation of the EU energy mix: revision of EU ETS for 2021-2030 phase 4; the new Effort Sharing Decision (national GHG caps for the non-ETS sectors for 2030); new policy for 2021-2030 on biomass and biofuels, reviewing the RES and CO2 geological storage framework law etc);

- Research and Innovation: 2030 pathways initiative, Horizon 2020, the SET Plan, ways of coordinating the regulatory and investment decisions.

In this context, it is worth mentioning the comment of the IEA Executive Director Maria van der Hoeven, who outlines that although a strong Energy Union is necessary to achieve the ambitious 2030 targets, ‘such a union should not represent a buyer’s cartel. Rather, it should feature an integrated energy market and effective climate and energy policies’ (press release).

Although a sound policy framework is important for the EU, there is certainly some scepticism associated with the Energy Union initiative, as well as worries regarding new regulations, which may potentially distort the market. Being held before the conference in Riga (6 February 2015) aimed at discussing the Energy Union from the policy perspective, the IX Energy Forum had a particular added value, as it brought the perspectives of the CEE countries on the initiative to the forefront, while also, involved industry representatives and consultants.

The fear of new regulations that would come together with the new policy structure and their impact on the markets and investments was expressed by a number of exerts. While investments in the EU in general dropped 15 % compared to 2007 according to DG ECOFIN, some 200 billion EUR of investments per year is needed to meet the 2030 political goals. In order to achieve that, finding a balance and fine-tuning the pace of developing and scaling up technological innovation on the one hand and regulations on the other is one of the hardest tasks. It is particularly challenging bearing in mind the different pace of development of EU energy markets.

For instance, countries like Poland, are definitely not aiming for the reduction of coal’s role in the energy mix as it projects to have 40% of energy from coal by 2030. At the same time, the fact that Germany does not reduce the amount of allowances that it auctions on yearly bases, means that its strategy of decreasing the number of coal-fired power plants will not necessarily have de facto impact on the overall CO2 emissions reduction. However, a common scheme of supporting investments in the sector is needed, despite the difference in investment climates across the member states. While in Western Europe power consumption is likely to decrease, the CEE countries are likely to see an increase in consumption of some 2-3% over the coming years.

Revising the ETS remains to be a challenge, but one thing is for sure: even though currently the industry is paying 7 EUR per tonne CO2, making it 40/50/60 EUR would not result in phasing out the coal plants (According to GE Reports, ‘Balancing the Energy Economy’ seminar, Science Business, Brussels, 20 January 2015). Bearing in mind EU’s 2050 decarbonisation objectives, the issue is to ensure that the energy transition envisaged is indeed ‘a transition, and not a revolution that would destroy industries’ (Stephan Reimelt, President and CEO, GE Europe, ‘Balancing the Energy Economy’ seminar, Science Business, Brussels, 20 January 2015). From this point of view, it is crucial to underpin the formation of the Energy Union by the robust energy systems that integrate RES, hydrocarbons and energy saving technologies and hybrid systems (RES with natural gas backup). This means thinking about the competition between systems of energy sources with different configurations rather than competition between types of energy sources alone.

Another acute question that has been high on the agenda is how much dependence on external suppliers should a sustainable Energy Union allow?

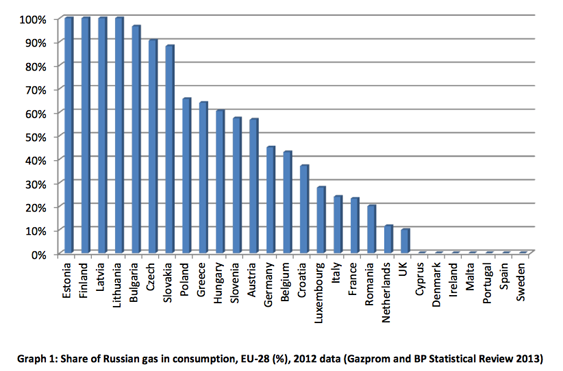

Energy dependence is an ambiguous question in itself. On the one hand, the CEE countries indeed are highly dependent on gas supplies from Russia, as the latter enjoys an exclusive dominant position in the markets (see Graph 1).

|

| Source: Clingendael International Energy Progarmme, Fact Sheet |

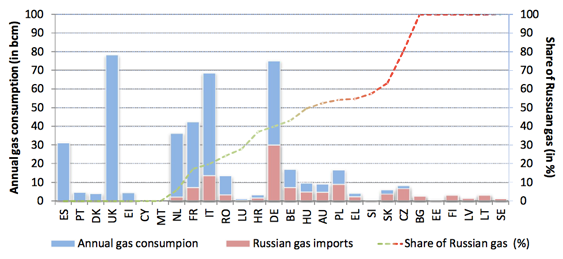

At the same time, ‘the gas markets of these …member states are relatively small…[Hence,] the total consumption of Bulgaria, Sweden, Finland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia amounts to 12.2 bcm, i.e. roughly 16% of the German gas demand’ (Picture 2).

|

| Picture 2: Russian gas in the total gas consumption of the EU-28 (aggregated 2012 data) Source: CEPS, Is Europe vulnerable to Russian gas cuts? Arno Behrens and Julian Wieczorkiewicz, 12 March 2014 (p.3) |

This comparison puts in perspective the energy dependency issue of the members of the Energy Union, but certainly leaves open yet another question to be addressed by the new structure. It is clear that Russian gas is currently an indispensable element of the energy mix for both, CEE countries, as well as Western Europe.

What remains to be seen is whether the EU is able to develop a common platform for energy diplomacy in the framework of Energy Union that would be working on the ground, or would that be again business as usual.

Discussion (0 comments)