Why "energy independence" means less power for the US, not more

on

Why "energy independence" means less power for the US, not more

American energy observers are super-excited about the huge unconventional prospects popping up all over the Americas. "Energy independence" is the new buzz word: with a bit of help from the likes of Canada and Brazil, the US can pack up, go home, and recycle petrodollars in its own back yard, the pundits say. But they are forgetting one thing: become "independent" and you lose your power in the world. Besides, Brazil, Canada and other countries in the Americas may have other ideas. For Europe, though, the new American independence game should be a wake-up call.

|

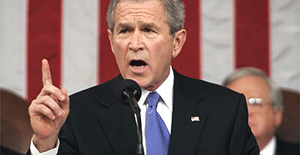

| President Bush delivers his fifth State of the Union address and warns that 'America is addicted to oil' (photo: Pablo Martinez Monsivais/AP) |

If we take the US first – the shale gas revolution has seen America rocket up the league of global gas producers to take top spot, above Russia, providing a large chunk of domestic supply. Unconventional oil endowments are believed to be more than 2 trillion barrels – much of which sits in shale rock. This is more than all of the world’s proven reserves, though of course those 2 trillion are not proven reserves. Analysts expect to see production of up to 1.5mb/d (million barrels per day) in the next few years from the Great Plains alone. (Note that the US is the third-largest oil producer in the world, and according to the BP Statistical Review of Energy, production has already steadily grown from 6.7 mb/d in 2008 to 7.5 mb/d in 2010).

Heavier oils also remain a distinct possibility in the US, where technology has been developed that heats up rocks to sweat liquids out. Offshore production in the Gulf of Mexico is expected to see a sharp upturn as drilling is getting back into full swing. Technically recoverable reserves in the outer continental US shelf weigh in at around 93billion barrels – almost as much as Iraq’s proven reserves. If new plays on the East and West coast are opened up for nodding donkeys to ride, expect to see the US become the world’s largest producer of liquid hydrocarbons.

Head North to Canada. After doubling proved reserves over the last six years to 32 billion barrels, the US’s northern neighbour sits on an additional 173billion barrels of ‘remaining established reserves’ in the sinews of its tar sands. Production from tar sands currently stands at around 1.5mb/d, with industry estimates suggesting output could reach at least 3mb/d by 2020 – rivalling the likes of Iran and outstripping Iraq. There is little reason to believe that production rates won’t increase further: most analysts are confident to pitch significantly higher, towards 5, 6, or even 7mb/d.

Head down South and things become even more enticing. In Brazil, Petrobras has declared its deep-water Tupi and Iracema fields should see additional pre-salt discoveries boost proved reserves from 14.9billion to 35 billion barrels by 2014. Assuming things go well a mile under the Atlantic surface, Brazil could be producing anything up to 5mb/d by 2020 – around half of Saudi Arabia. If biofuel output is added, production figures come out considerably higher.

Brazil’s growth will certainly help to focus minds in Venezuela. President Chavez has been extremely good at revising reserves up to a staggering 296.5 billion barrels of late (in what could be coined a

| It's little wonder that this geological shake-up is prompting a serious rethink of the geopolitical energy map |

To cap the list, even Argentina is boasting ample new reserves in the Falklands – reserves that could one day bring them towards parity with Bolivia and Ecuador. Meanwhile Mexico is said to hold anything up to 680trillion cubic feet (19.2 billion cubic metres) of technically recoverable shale gas, which is over 4 times as much as Algeria’s proven reserves.

Admittedly all the usual technical, environmental and geological caveats apply to the Americas’ oil and gas numbers. Fracking and cracking is a dirty business; costs remain uncertain (in terms of benchmark prices; the potential for further technological innovation is uncertain. Peak oilers are only too happy to quote steep depletion rates in the US to salvage their ideological position, while further ‘Macondo moments’ are entirely possible given the engineering challenges involved in offshore prospects.

But even with these health warnings in place, the bottom line (irrespective of Venezuelan output), is that unconventional reserves in the US, Canada and South America far outstrip conventional Middle East and North African (MENA) plays. In oil, the scorecard shows 6.5 trillion unconventional Americas barrels vs. 1.2 trillion MENA conventional plays. It’s little wonder that this geological shake-up is prompting a serious rethink of the geopolitical energy map. The position of leading US observers, including some of the Founding Fathers of US energy analysis, is pretty clear: America can declare energy independence. Import dependence will go. The trade deficit will look a lot better. Dollars will stay in America rather than filling OPEC coffers. Oil will flow from North to South and South to North rather than East to West. Americas’ oil for American consumers at American prices.Some have even noted US superpower status is now back with a vengeance.

Geopolitical snags

It all sounds terrific, but there are several problems with this story. First of all, it’s a bit of a case of the signs hanging up in British pubs: “free beer tomorrow”. The lead times for most of this production is 2020-ish for some, 2030-ish for others. These resources might well one day make it to market, assuming the figures don’t prove to be bunk, but it will be “tomorrow” rather than today.

The fact is that over the next decade OPEC market share is going to be as concentrated as ever. The

| Ironic newsflash for the US: they aren't dependent on Middle East oil reserves, and haven't been for a long time |

Secondly, and probably even more importantly, there is the politics to consider. Ironic newsflash for the US: they aren’t dependent on Middle East oil reserves, and haven’t been for a long time. Washington

That’s before we even consider where the Gulf States decide to recycle their petrodollars in future. No security, no $? It’s certainly a question for the US to ponder – not only in terms of who they are going to sell their Treasuries too, but also what currency oil is priced in.

Middle East oil isn’t about oil for America, it’s ultimately about power. If the US wasn’t part of the Gulf energy game, it would have zero sway in Saudi, no powers of persuasion over Iranian nukes, no say in how the Arab Spring plays out or how Gulf Monarchies handle succession problems in future.

And even though WTI and Brent are showing major spreads, geopolitical flashpoints still affect US

| Middle East oil isn't about oil for America, it's ultimately about power |

Seven Sisters

There could of course be a plan B that makes the energy independence narrative more credible, and it’s called China. That is to say: an orderly re-division of geopolitical labour between the US and China. However, this is not likely to happen, precisely because Washington wants to continue playing a central geopolitical role.

|

| Conoco's facilities at the Christina Lake project in the oil sands of Alberta, Canada (photo: conocophillips.com) |

Turn to Brazil and we see a similar picture. Sao Paulo secured a $10billion loan from China to help finance Brazil’s $174billion five year strategic energy plan, directly paid back in oil supplies to Sinopec and CNPC. Argentina has also been on China’s resource list, not to mention Venezuela, where Caracas has received $12billion(and rising) in Chinese loans, on the back of PDVSA oil supplies to Beijing.

This isn’t a case of Seven Sisters, then, but of Three Chinese Brothers getting the Americas’ unconventional ball rolling. Even in the US, China finally managed to gain a stake in Chesapeake Energy which is developing Eagle Ford shale in Texas. It rather makes you wonder what all the Unocal fuss was about in 2005.

But China is nothing if not strategic. Beijing might just be willing to trade in its assets in the Americas, but only if the US is willing to accept that the Middle East becomes a Chinese lake. That means Saudi Arabia (where China sources around 1mb/d), Iraq, Iran, and arguably Central Asian players – all of which would fall within the Chinese sphere. ‘East is East, West is West’.

If current ‘hard balancing’ between the US and China in South Asia is anything to go by, this looks remarkably unlikely to happen. Washington will fight Beijing for every inch of geopolitical territory it can maintain. The US finger has already been firmly stuck in the Vietnamese dyke, more digits will be applied across the Indian Ocean.

Washington should therefore be very careful as too how far and how quickly it plays its ‘energy independence’ hand. It might look an attractive option from Capitol Hill, but it will come with serious geopolitical downside risks that many in the US aren’t yet fully willing to contemplate. Losing the Middle East would be a bitter US pill to swallow; many MENA states would hardly relish a rapid US withdrawal from the region either.

And even if the US and China went for a grand bargain, swapping the Gulf for the Americas (with West Africa thrown into the Atlantic mix and East Africa heading to the Pacific Basin), there is yet another little problem: the attitude of the US’s “neighbours” in the Americas. Canada, Venezuela, Mexico, Bolivia, Ecuador and Argentina all share a common purpose on the hydrocarbon front.

They realise that relying on a single source of supply and a single source of demand isn’t particularly

| If we take the forecasts for the Americas seriously, the US will not only lose global sway as the independence bug bites, but it might struggle to retain a dominant role in its own backyard |

If we take the forecasts for the Americas seriously, the US will not only lose global sway as the independence bug bites, but it might struggle to retain a dominant role in its own backyard. A change of government could be all it takes for Brazil to join OPEC, Canada will play hard ball with the US over its Arctic assets, and even when Chavez is gone, don’t expect his successor(s) to be any more pro-American. New found petro-states will not be traditional US silos.

Straight and narrow

Given its nearest neighbours aren’t buying the energy independence line, the smarter move for Washington is not to keep jumping up and down about going solo, but to use the threat of unconventional production to keep OPEC on the straight and narrow as cartel control tightens in the next ten years. The prospect of flooded markets is the last thing Arab leaders want, either now, or in future. But make OPEC too nervous about unconventional gains, and they could go for the atomic option of scuppering unconventional output by depressing prices.

Indeed, the fact that the US has new options from geological shifts is what’s interesting here. Forget energy independence as a concept – it’s not going to happen in the stark terms US analysts have

| Any notion that Europe needs to reach out towards major consumers in the East to offset future Russian pressures at both ends of the Eurasian pipeline, is not one that Brussels seems willing or ready to accept |

The biggest ball likely to be dropped from US energy independence actually relates to Europe. Libya should be a massive wakeup call for the EU – not least because it told us far more about European deficiencies than US preferences. Growing US recoil will clearly affect European supplies, increasing Europe’s structural dependence on Russia oil and gas as its default supply option. Assuming Europe continues its current (dis)orderly management of decline, Brussels will fail to open up new MENA or Central Asian reserves, because its security sealant is too leaky for upstream players to take politically seriously.

|

| (photo: Acus.org) |

So while the US might be tempted by the allure of energy independence, it will probably end up meaning far less to Washington than it eventually does for Brussels. In this sense, American independence might take on a whole new transatlantic definition.

PS. By way of footnote, with the unconventional genie out of the bottle, any hope that climate mitigation will gain a serious stake in the global energy game is dead. It’s not just the Americas sitting on massive unconventional reserves, but China, Russia, India and Europe. On the day we all declare energy independence we might want to stop and think whether we have much of a planet worth living on anyway. Certain trade balances might eventually look a bit better though.

Discussion (0 comments)