Britain's Electricity Supply Crunch Forecast to Become Much Worse

February 03, 2016

on

on

Great Britain is facing an electricity supply crunch because the margin between available electricity generation capacity and peak winter demand has fallen to worryingly low levels. Power system operator National Grid has already had to implement new measures of last resort to maintain supply – and may well have to do so again before winter is out, despite this being the mildest winter in the UK since records began. What is shocking about this “electricity supply crunch” is that it was predicted as long ago as 2010 by, amongst others, the regulator of the UK’s electricity and gas markets, Ofgem. And this is just the beginning, according to a report just published by the UK’s Institute of Mechanical Engineers. It says that, without appropriate policy reforms, a decade from now the UK will face not today’s worryingly slim capacity margin but a yawning chasm between available generation and demand of some 40-55%.

On November 4th 2015 the operator of Britain’s electricity transmission system, National Grid, had to implement measures of last resort to mitigate the risk of having to cut supply to customers. On what was a calm, mild autumn day, four ageing coal-fired power stations went down at very short notice, leaving the electricity system short of sufficient generation capacity to meet the late afternoon demand peak.

As it became clear, around lunchtime, that supply would become very tight later in the day, National Grid issued a Notice of Insufficient System Margin (NISM), alerting power plants that more generation capacity would be needed between 16:30 and 18:30.

Because it was calm, the nation’s 13 GW of onshore and offshore wind power capacity was generating only some 400 MW of electricity. The nation’s 8 GW of solar power capacity could not help because by then it would be dark.

To help balance supply and demand, National Grid decided that – as well as asking generators to make more capacity available – it would for the first time implement a scheme called Demand Side Balancing Reserve (DBSR). Under this scheme, introduced in 2014, businesses can be asked to reduce their usage in exchange for payment. Between 17:00 and 18:00 numerous businesses cut their demand by powering down air-conditioning and ventilation systems.

As prices in the wholesale market soared, National Grid also had to pay one electricity generator £2,500/MWh – some 40 times the typical market price – for a short period to ensure that enough generation would be available to meet the demand peak.

The strategy worked. The emergency passed without any inconvenience to consumers. But it left people asking why National Grid was having to take such action when the current electricity crunch was predicted – by no less than the regulator of Britain’s power and gas markets, Ofgem – as long ago as 2010.

in March 2010 I reported on Ofgem’s concerns in an article for European Energy Review entitled “Britain’s Electricity Sector Headed for a Cliff Edge”. Re-reading it now, I am struck by how accurate Ofgem’s predictions have turned out to be, despite major – some would say ill-thought-through – reforms to Britain’s electricity market:

“Britain’s electricity generation system is looking decidedly rickety,” I wrote. “By 2016, many of its older, dirtier coal-fired stations will be forced to close, because of the European Union’s Large Combustion Plant Directive. The EU’s Industrial Emissions Directive will lead to further closures by 2020. Many of Britain’s nuclear power stations have already been shut down and many more will have to be shut over the coming decade because they are reaching the end of their lives. Meanwhile, political uncertainty and financial crisis have slowed investment in new plant.

“In its Project Discovery consultation paper released last month, UK energy regulator Ofgem concludes that if demand grows as expected, Britain faces a yawning gap between the electricity it will need and the amount it will be able to generate in the second half of this decade. It is unthinkable that the government will, to use the current buzz-phrase, allow ‘the lights to go out’. But many commentators, including energy regulator Ofgem, believe urgent reforms are needed to ensure the necessary investment in new plant is made.”

Ofgem’s report presented five policy packages that the government could choose from to implement electricity market reform (EMR). They ranged, in the words of one industry source, from the “fairly mild to the fairly mad”. At the “mad” end of the spectrum was an eyebrow-raising proposal to establish a central buyer of energy and capacity that would determine the amount and type of new electricity generation needed, and could also tender for new gas infrastructure.

It was not long after this, in May 2010, that the then Labour government was replaced by a coalition of the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats. EMR went ahead, eventually – but the policies that were implemented have not had the impact on new investment that the government, Labour or coalition, had hoped.

The new coalition government set out to formulate policy proposals that would decarbonise electricity generation while maintaining supply security and keeping the market competitive – not an easy trick to pull off. Not surprisingly, given its political complexion, it shied away from the heavily interventionist approach of establishing a central buyer.

It was not until December 2013 – following much consultation and debate – that a new Energy Act received Royal Assent, enshrining in law the two main reforms that ended up at the centre of the EMR process:

* Price guarantees for new low-carbon power projects – To incentivise low-carbon generation investments, long-term “contracts for difference” (CFDs) were introduced to top up payments when wholesale prices are low and to claw back money when they are high. These effectively give low-carbon generators – including, controversially, nuclear power generators – a guaranteed price, known as the “strike price”, for their output.

A problem with the CFDs is that some low-carbon sources, notably wind and solar, are intermittent, and so cannot be relied upon to contribute to capacity margin in all circumstances (as we saw on 4th November). As for nuclear, which theoretically could, the earliest that new nuclear will be available in the UK is 2025 (and perhaps not even then given the recent delay in reaching final investment decision on EDF’s proposed new project at Hinkley.)

* A Capacity Market (CM) – To encourage the construction of reserve plants, or demand-reduction measures, payments are to be made under a capacity mechanism. The objective is to ensure “to encourage the investment needed to replace older power stations, provide backup for more intermittent and inflexible low-carbon generation sources, and support the development of more active demand management in the electricity market”.

One problem with the CM is that the auctions held so far, in 2014 and 2015, are for capacity or demand-reduction measures in 2018/19 and 2019/20, and so do not contribute to current margin tightness. Another criticism – especially following the latest auctions, the results of which were announced in December of last year – is that a lot of the available money has gone to highly-polluting plant, such as diesel-fired generating units.

In its role as system operator of Britain’s electricity transmission network, National Grid produces what are known as Future Energy Scenarios (FES) “to help government, our customers and other stakeholders make informed decisions”.

The scenarios show “a range of plausible and credible pathways for the future of energy, from today out to 2050” and are used by Ofgem in its analysis of electricity supply security.

In a report on electricity supply security published last year, Ofgem comments on National Grid’s scenarios and assesses the risks to security of supply in the winters of 2015/16, 2016/16 and 2017/18. Some of its key conclusions are summarised in the charts below.

Click to enlarge.

Ofgem notes that peak winter demand in the UK has been on a downward trend over the past decade. Adjusted for average weather conditions, it fell by 6 GW between winter 2005/06 and winter 2014/15. Peak demand in 2015/16 is expected to be a little higher than in 2014/15 but to resume its downward trend from 2016/17.

However, installed generation capacity is also on a downward trend, partly for the reasons outlined above – the closure of ageing coal and nuclear plants – but also because gas-fired plants are leaving the market, either permanently or through mothballing, because of poor economics. National Grid expects a net reduction of around 4 GW between 2014/15 and 2015/16 and a further reduction in 2016/17, before an upturn in 2017/18, as some mothballed plant is assumed to return to the market in preparation for participation in the CM.

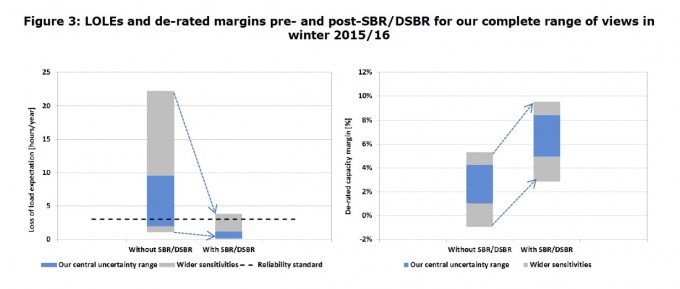

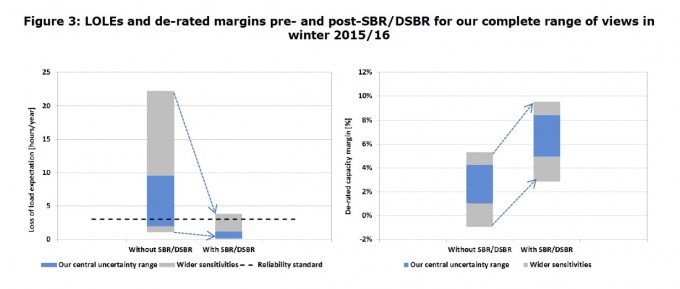

Winter 2015/16 would have been tricky for National Grid were it not for the two New Balancing Services (NBS) explained in the box below: the Supplemental Balancing Reserve (SBR) and the Demand Side Balancing Reserve (DSBR). Without them, National Grid would have struggled to meet the power reliability standard required by the government, and de-rated margins (which allow for availability not being 100% in the real world) would have been an extremely tight 1-4% , even in Ofgem’s “central uncertainty range”. With them, National Grid is able to stay within the reliability standard in most projected outcomes and margins are a much less worrying, though still tight, 3-8.5% in Ofgem’s central range. [See chart above].

However, the SBR and DSBR, introduced because of concerns over supply security this winter, are due to expire at the end of the winter – so National Grid is consulting on extending them. The the left chart in the box shows that winter 2016/17 looks even more worrying than 2015/16. Winter 2017/18 looks a lot more comfortable because of the assumption that more plant will come online to prepare for participation in the CM.

Another change of government later – the Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition was replaced by a majority Conservative government in May of last year – the current Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change, Amber Rudd, last November set out her proposals for further reform of the electricity sector, exactly a fortnight after the November 4th “electricity crunch”.

Yet again, UK energy reform proposals are proving controversial. The centrepiece of Rudd’s speech was a proposal to close down all coal-fired generation plant by 2025, with much of that capacity being replaced with gas-fired plant.

“In the next ten years it’s imperative that we get new gas-fired power stations built,” said Rudd. “We need to get the right signals in the electricity market to achieve that.”

Given the signal failure of government policy to date to persuade investors to construct more gas-fired combined-cycle gas turbine (CCGT) plant – rather than the current reality of existing gas-fired power stations closing or being mothballed because of poor economics – it will be interesting to see the detail of how she proposes to achieve that.

A robust and detailed response to her speech has come from the Institute of Mechanical Engineers in a report published on 26th January:

“With little or no focus on reducing electricity demand, the retirement of the majority of the country’s ageing nuclear fleet, recent proposals to phase out coal-fired power by 2025 and the cut in renewable energy subsidies, the UK is on course to produce even less electricity than it does at the moment,” says lead author, Dr Jenifer Baxter, the institute’s Head of Energy and Environment.

“We cannot rely on CCGTs alone to plug this gap, as we have neither the time, resources nor enough people with the right skills to build sufficient power plants. Electricity imports will put the UK’s electricity supply at the mercy of the markets, weather and politics of other countries, making electricity less secure and less affordable … Under current policy it is almost impossible for UK electricity demand to be met by 2025.”

The report claims that the UK would be left with an electricity supply gap of 40-55%. Now that really would be an electricity crunch.

Image: Heysham Power Station. By: Rwendland. CC-BY licence.

On November 4th 2015 the operator of Britain’s electricity transmission system, National Grid, had to implement measures of last resort to mitigate the risk of having to cut supply to customers. On what was a calm, mild autumn day, four ageing coal-fired power stations went down at very short notice, leaving the electricity system short of sufficient generation capacity to meet the late afternoon demand peak.

As it became clear, around lunchtime, that supply would become very tight later in the day, National Grid issued a Notice of Insufficient System Margin (NISM), alerting power plants that more generation capacity would be needed between 16:30 and 18:30.

Because it was calm, the nation’s 13 GW of onshore and offshore wind power capacity was generating only some 400 MW of electricity. The nation’s 8 GW of solar power capacity could not help because by then it would be dark.

To help balance supply and demand, National Grid decided that – as well as asking generators to make more capacity available – it would for the first time implement a scheme called Demand Side Balancing Reserve (DBSR). Under this scheme, introduced in 2014, businesses can be asked to reduce their usage in exchange for payment. Between 17:00 and 18:00 numerous businesses cut their demand by powering down air-conditioning and ventilation systems.

As prices in the wholesale market soared, National Grid also had to pay one electricity generator £2,500/MWh – some 40 times the typical market price – for a short period to ensure that enough generation would be available to meet the demand peak.

The strategy worked. The emergency passed without any inconvenience to consumers. But it left people asking why National Grid was having to take such action when the current electricity crunch was predicted – by no less than the regulator of Britain’s power and gas markets, Ofgem – as long ago as 2010.

Headed for a cliff edge

in March 2010 I reported on Ofgem’s concerns in an article for European Energy Review entitled “Britain’s Electricity Sector Headed for a Cliff Edge”. Re-reading it now, I am struck by how accurate Ofgem’s predictions have turned out to be, despite major – some would say ill-thought-through – reforms to Britain’s electricity market:

“Britain’s electricity generation system is looking decidedly rickety,” I wrote. “By 2016, many of its older, dirtier coal-fired stations will be forced to close, because of the European Union’s Large Combustion Plant Directive. The EU’s Industrial Emissions Directive will lead to further closures by 2020. Many of Britain’s nuclear power stations have already been shut down and many more will have to be shut over the coming decade because they are reaching the end of their lives. Meanwhile, political uncertainty and financial crisis have slowed investment in new plant.

“In its Project Discovery consultation paper released last month, UK energy regulator Ofgem concludes that if demand grows as expected, Britain faces a yawning gap between the electricity it will need and the amount it will be able to generate in the second half of this decade. It is unthinkable that the government will, to use the current buzz-phrase, allow ‘the lights to go out’. But many commentators, including energy regulator Ofgem, believe urgent reforms are needed to ensure the necessary investment in new plant is made.”

Ofgem’s report presented five policy packages that the government could choose from to implement electricity market reform (EMR). They ranged, in the words of one industry source, from the “fairly mild to the fairly mad”. At the “mad” end of the spectrum was an eyebrow-raising proposal to establish a central buyer of energy and capacity that would determine the amount and type of new electricity generation needed, and could also tender for new gas infrastructure.

Electricity market reform

It was not long after this, in May 2010, that the then Labour government was replaced by a coalition of the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats. EMR went ahead, eventually – but the policies that were implemented have not had the impact on new investment that the government, Labour or coalition, had hoped.

The new coalition government set out to formulate policy proposals that would decarbonise electricity generation while maintaining supply security and keeping the market competitive – not an easy trick to pull off. Not surprisingly, given its political complexion, it shied away from the heavily interventionist approach of establishing a central buyer.

It was not until December 2013 – following much consultation and debate – that a new Energy Act received Royal Assent, enshrining in law the two main reforms that ended up at the centre of the EMR process:

* Price guarantees for new low-carbon power projects – To incentivise low-carbon generation investments, long-term “contracts for difference” (CFDs) were introduced to top up payments when wholesale prices are low and to claw back money when they are high. These effectively give low-carbon generators – including, controversially, nuclear power generators – a guaranteed price, known as the “strike price”, for their output.

A problem with the CFDs is that some low-carbon sources, notably wind and solar, are intermittent, and so cannot be relied upon to contribute to capacity margin in all circumstances (as we saw on 4th November). As for nuclear, which theoretically could, the earliest that new nuclear will be available in the UK is 2025 (and perhaps not even then given the recent delay in reaching final investment decision on EDF’s proposed new project at Hinkley.)

* A Capacity Market (CM) – To encourage the construction of reserve plants, or demand-reduction measures, payments are to be made under a capacity mechanism. The objective is to ensure “to encourage the investment needed to replace older power stations, provide backup for more intermittent and inflexible low-carbon generation sources, and support the development of more active demand management in the electricity market”.

One problem with the CM is that the auctions held so far, in 2014 and 2015, are for capacity or demand-reduction measures in 2018/19 and 2019/20, and so do not contribute to current margin tightness. Another criticism – especially following the latest auctions, the results of which were announced in December of last year – is that a lot of the available money has gone to highly-polluting plant, such as diesel-fired generating units.

Supply security scenarios

In its role as system operator of Britain’s electricity transmission network, National Grid produces what are known as Future Energy Scenarios (FES) “to help government, our customers and other stakeholders make informed decisions”.

The scenarios show “a range of plausible and credible pathways for the future of energy, from today out to 2050” and are used by Ofgem in its analysis of electricity supply security.

In a report on electricity supply security published last year, Ofgem comments on National Grid’s scenarios and assesses the risks to security of supply in the winters of 2015/16, 2016/16 and 2017/18. Some of its key conclusions are summarised in the charts below.

Click to enlarge.

Ofgem notes that peak winter demand in the UK has been on a downward trend over the past decade. Adjusted for average weather conditions, it fell by 6 GW between winter 2005/06 and winter 2014/15. Peak demand in 2015/16 is expected to be a little higher than in 2014/15 but to resume its downward trend from 2016/17.

However, installed generation capacity is also on a downward trend, partly for the reasons outlined above – the closure of ageing coal and nuclear plants – but also because gas-fired plants are leaving the market, either permanently or through mothballing, because of poor economics. National Grid expects a net reduction of around 4 GW between 2014/15 and 2015/16 and a further reduction in 2016/17, before an upturn in 2017/18, as some mothballed plant is assumed to return to the market in preparation for participation in the CM.

Winter 2015/16 would have been tricky for National Grid were it not for the two New Balancing Services (NBS) explained in the box below: the Supplemental Balancing Reserve (SBR) and the Demand Side Balancing Reserve (DSBR). Without them, National Grid would have struggled to meet the power reliability standard required by the government, and de-rated margins (which allow for availability not being 100% in the real world) would have been an extremely tight 1-4% , even in Ofgem’s “central uncertainty range”. With them, National Grid is able to stay within the reliability standard in most projected outcomes and margins are a much less worrying, though still tight, 3-8.5% in Ofgem’s central range. [See chart above].

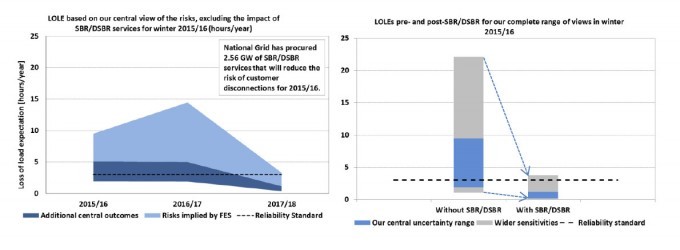

However, the SBR and DSBR, introduced because of concerns over supply security this winter, are due to expire at the end of the winter – so National Grid is consulting on extending them. The the left chart in the box shows that winter 2016/17 looks even more worrying than 2015/16. Winter 2017/18 looks a lot more comfortable because of the assumption that more plant will come online to prepare for participation in the CM.

More energy reforms in the pipeline

Another change of government later – the Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition was replaced by a majority Conservative government in May of last year – the current Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change, Amber Rudd, last November set out her proposals for further reform of the electricity sector, exactly a fortnight after the November 4th “electricity crunch”.

Yet again, UK energy reform proposals are proving controversial. The centrepiece of Rudd’s speech was a proposal to close down all coal-fired generation plant by 2025, with much of that capacity being replaced with gas-fired plant.

“In the next ten years it’s imperative that we get new gas-fired power stations built,” said Rudd. “We need to get the right signals in the electricity market to achieve that.”

Given the signal failure of government policy to date to persuade investors to construct more gas-fired combined-cycle gas turbine (CCGT) plant – rather than the current reality of existing gas-fired power stations closing or being mothballed because of poor economics – it will be interesting to see the detail of how she proposes to achieve that.

A robust and detailed response to her speech has come from the Institute of Mechanical Engineers in a report published on 26th January:

“With little or no focus on reducing electricity demand, the retirement of the majority of the country’s ageing nuclear fleet, recent proposals to phase out coal-fired power by 2025 and the cut in renewable energy subsidies, the UK is on course to produce even less electricity than it does at the moment,” says lead author, Dr Jenifer Baxter, the institute’s Head of Energy and Environment.

“We cannot rely on CCGTs alone to plug this gap, as we have neither the time, resources nor enough people with the right skills to build sufficient power plants. Electricity imports will put the UK’s electricity supply at the mercy of the markets, weather and politics of other countries, making electricity less secure and less affordable … Under current policy it is almost impossible for UK electricity demand to be met by 2025.”

The report claims that the UK would be left with an electricity supply gap of 40-55%. Now that really would be an electricity crunch.

The role of new balancing services in securing supply

Click to enlarge.

The chart on the left shows Ofgem’s view of Loss of Load Expectation (LOLE) for the winters of this year (2015/16), next year and the year after, excluding the contribution that could be made by two New Balancing Services (NBS), known as the Supplemental Balancing Reserve (SBR) and the Demand Side Balancing Reserve (DSBR).

LOLE is a metric used by Ofgem to assess security of supply. It is the average number of hours in a year when Ofgem expects there will be insufficient supply available in the market, meaning that system operator National Grid “may need to take action that goes beyond the normal market operations to balance the system”. Outside the market, National Grid can use the SBR and DSBR to especially contract power stations to provide power (SBR) or businesses to reduce consumption (DSBR), in return for a payment, when capacity margins look tight.

The dotted line shows the power reliability standard required by the government – 3 hours per year of LOLE. It does not imply 3 hours of power cuts, but rather three hours of National Grid having to take exceptional action to balance the system.

The light blue area shows the range of risks to electricity security of supply implied by National Grid’s Future Energy Scenarios (FES) document. These fall within Ofgem’s central view of the level of security expected to be delivered by the market alone. The dark blue area shows additional central outcomes arising from Ofgem’s analysis. Expected outcomes vary because of a range of factors, such as weather conditions.

The chart shows a wide range of possible outcomes outside the power reliability standard for this year and an even wider range for 2016/17. Risks reduce in 2017/18, says Ofgem, “mainly due to [generation] plant returning to the market”.

The chart on the right, says Ofgem, “shows how the SBR and DSBR that National Grid has procured for this winter have brought the risks to security of supply within the government’s reliability standard (3 hours LOLE) for a wide range of credible outcomes”. The SBR and DSBR expire at the end of the 2015/16 winter so National Grid is consulting on extending them.

Image: Heysham Power Station. By: Rwendland. CC-BY licence.

Read full article

Hide full article

Discussion (1 comment)