A real option: more Energiewende to lessen gas dependence

on

A real option: more Energiewende to lessen gas dependence

Can the Ukraine crisis force Germany to backtrack on the Energiewende? No, regardless of Poland’s off-the-cuff critique. But it’s fuelling anew the debate in Germany over security of supply.

|

| (c) Filip Robert |

Poland’s prime minister Donald Tusk went as far as claiming that Germany’s Energiewende is responsible for Berlin’s limited diplomatic leverage over against Russia. With Poland’s own energy interests in mind and not necessarily Germany’s geopolitical clout, Tusk claimed the Energiewende and rigorous EU climate goals mean greater demand for Russian gas, and less for Polish coal. Poland’s conclusions for its own supply security: more coal production, a first-ever nuclear program, and shale gas exploration.

In Germany, Tusk’s logic makes sense to the fossil-fuel lobby and their remaining spokesmen in the Bundestag, like the Christian Democrat MP Michael Fuchs. “Donald Tusk is absolutely right,” he said. “ We can’t be too dependent on one supplier (...) We have to correct the Energiewende.”

Russian gas and oil are indeed very important to Germany, in particular gas for heating; only a small volume of the gas supply is used for electricity generation. Nearly 40 percent of Germany’s gas comes from Russia (Norway supplies 35 percent, the Netherlands 22 percent). As for Russia, 70 percent of Russia’s exports to Germany, its third largest trading partner, are in the form of hydrocarbons. This significant, mutually beneficial relationship is why most energy experts doubt that even “a new Cold War” will fundamentally alter the status quo. Most of the gas and oil contracts are so-called Long Term Contracts of 15 to 25 years anyway. Moreover, with an increasingly diversified gas market, alternatives to Russian gas are ever more plentiful.

Yet, whether push comes to shove or not between the EU and Russia, the heightened risk factor is there, as are worst-case scenarios posing interrupted supply.

So, the first question: might the ongoing crisis cause Germany to rethink its nuclear-power phase-out? After all, Germany is currently scrambling to ensure reserve power capacity for the day when the next batch of nuclear reactors go offline. Nuclear power currently provides a sizable chuck of Germany’s “must-run capacity”, which will have to be replaced. State-of-the-art gas-fired works are meant to provide most of this flexible reserve capacity. But if the gas isn’t there?

The response from Berlin is unequivocally “nein.” The nuclear phase-out is etched in stone, German officials underscored again on the third anniversary of the Fukushima disaster in Japan on March 11. There’s no discussion at the moment in Germany about reversing or even extending the duration of the phase-out. There are a range of options under discussion for addressing the capacity dilemma, as the Berlin-based think tank Agora Energiewende points out, all of which relieve the burden on gas in terms of reserve capacity. The Merkel government is currently deliberating on the measures to pursue.

Furthermore, when it comes to nuclear power there’s a point that Tusk and the other nuclear-minded Central Europeans gloss over: 30 percent of the uranium used as fuel in EU Europe’s nuclear power plants is imported from Russia, the bloc’s largest single source. If nuclear power is meant to decrease dependence on Russia, this supply would have to be replaced.

Naturally, the first place to look to bolster the security of gas supply is not nuclear power but gas-supply alternatives to Gazprom. One option is unconventional gas like shale gas: in form of imports from the US or domestic production in Germany and in Europe as a whole. The possibility of US exports appeals to both the Central Europeans (who buy 70 to 100 percent of their gas from Russia) and much of the US political establishment, which thinks it can be lucrative and have a geostrategic impact.

Yet the US is at least two years away from having the infrastructure in place to export any LNG at all across the Atlantic, much less enough to make a real dent in Russian exports. Nor is there a consensus, even in the US among energy experts, that shale gas reserves in US are plentiful enough to export abroad. European LNG import terminals are running well below capacity so Europe could import large amounts of LNG. However, Europe would have to compete with Asia in a tight market. Indeed, if that were to happen, everyone could end up paying exorbitant prices.

As for domestic production in Europe, there is neither consensus on the extent of shale gas reserves nor on the ecological fallout of hydraulic fracking. The UK may well be the first European country to develop significant shale gas, as its government is very keen to. Otherwise the Central Europeans are pretty much alone in their enthusiasm for shale gas, at least at the moment.

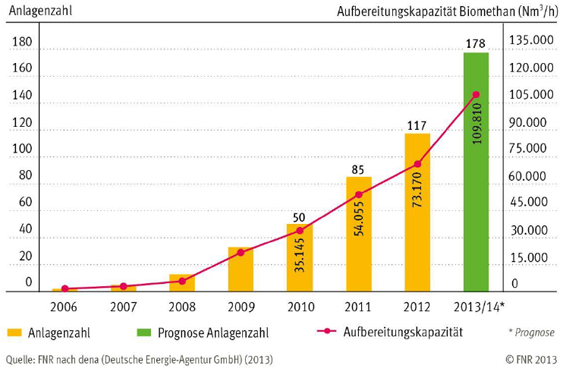

Tusk didn’t mention the option of biogas, for example in the form of bio-methane, which some German experts argue have potential to replace as much as a sixth of Germany’s natural gas consumption. Some 125 biogas plants currently feed bio-methane into Germany’s gas grid (see chart 1), accounting for just a sliver of Germany’s heat generation. Most of it is used in decentralized CHP plants, which, among other things, can provide flexible, reserve power capacity. But biogas potential studies from the Fachagentur Nachwachsende Rohstoffe estimate that biogas in Germany offers a technical primary energy potential of 500 petajoule a year by 2020. The potential in Poland, Belarus and Ukraine is considerably greater.

|

| Chart 1 - Biomethane, development of the number of plants and their processing capacity |

And then, according to Tusk, there is coal. Germany and Poland are the two biggest consumers of coal in the EU, respectively. In Poland, coal generates 92 percent of its electricity and 89 percent of its heat; Germany generates 45 percent of its power with coal, a figure that has crept upwards in the last two years, a distinct blemish on the Energiewende. Poland clearly sees its own coal reserves, the volume of which is hotly disputed, as a means to energy independence. Standing in its way, as well as that of the German coal industry, are EU climate targets, which are currently under negotiation for 2030.

Yet both Poland and Germany, among other EU countries, import significant amounts of coal from Russia. (In 2010, the origin of 27 percent of the EU’s imported hard coal was Russia.) Russia accounts for just under 30 percent of Germany’s coal imports, second only to Columbia. The Polish coal industry, meanwhile, is in deep crisis; the high costs of its coal production force the country to import more than it exports. Its primary source for black coal today: Russia. Once the EU Emissions Trading Scheme is finally working, Polish coal will become even more costly compared to that of Russia.

In fact, “more Energiewende” may be just what the doctor ordered to wean Germany off Russian gas. Compared to the greening of its power sector,

| In fact, “more Energiewende” may be just what the doctor ordered to wean Germany off Russian gas |

In addition to bio-methane, geothermal and solar thermal systems, as well as wood-burning boilers and other biomass systems, are heating technologies that “can often be competitive with those using fossil fuels,” according to the IEA.

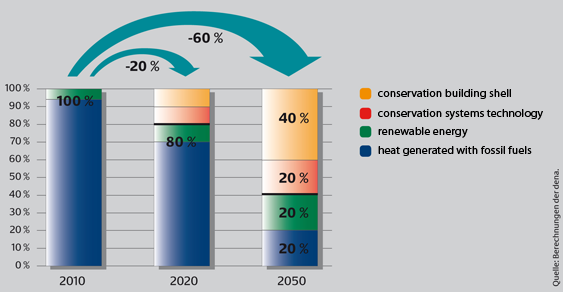

Indeed, some of these options are terra incognita, unlike the most effective, cost-relevant, and undisputed means to decrease imports and secure supply in the heating sector– namely energy efficiency. According to a 2013 study by the German Energy Agency (DENA), by 2020 energy efficiency measures could cut Germany’s final energy consumption in the heating sector (covering all sectors and energy sources, not just natural gas) by 16 percent. DENA estimates that by 2050, Germany could reduce its heat consumption in residential buildings by 60 percent, while renewables could cover another 20 percent of 2008-based consumption (see chart 2).

These are options that Donald Tusk would do well to consider before selling short the potential of the Energiewende.

|

| Chart 2 - Final energy consumption scenario (heat) for housing stock to meet the German government’s energy goals. Clarification: With a final energy saving by 60% in the entire building stock (heating + hot water) until 2050, primary energy consumption generated with fossil fuels can be reduced by 80% (goal of energy concept as set by the German government). Half of the remaining final energy will be covered by renewable energy. |

Discussion (0 comments)